The beginnings

The term ‘textile art’ emerged in the wake of the Lausanne Biennials during the Sixties and Seventies. Although entitled Tapestry Biennials, they were perceived as textile art events by contemporaries.

The initial pioneers were American women artists seeking to find their own art forms to set them apart from their male colleagues. They were encouraged by teachers such as Josef and Anni Albers and others who brought the Bauhaus tradition of experimentation to the New World when escaping from the Nazi regime. It is well worth reading the interviews with Claire Zeisler and others describing how these “dilettantes” became great textile artists (footnote 1).

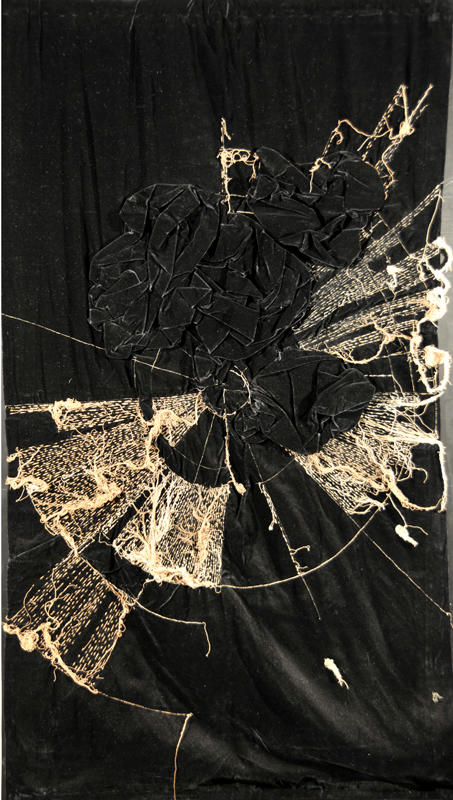

Eastern Europe saw a return to its own textile traditions at a very early stage during the Sixties. Predominantly, but not exclusively, it took place in Poland where Magdalena Abakanowicz created textile sculptures so powerful as to put paid to the question of whether they constituted applied art or fine art. It is significant that the Communist system of art promotion happened to have a positive effect on the liberation of the crafts from the label of applied art; while the regime considered painting and sculpture intellectually meaningful and thus dangerous, strictly monitoring their subject matter, it gave the crafts a free reign! This allowed many artists to go to ground in the crafts, and to continue producing subversive coded messages unnoticed.

After World War II, the Scandinavian countries also developed pioneering textile art based on folk art. Again, it was mostly women who ventured into fine textile art, breaking new ground and causing sensations. Scandinavian countries are characterised by their down-to-earth approach regarding the use of art: they developed modern textile designs for the textile and fashion industry as well as fine textile art, which was always associated with architecture and interior design in those countries.

Modern Japanese textile art arrived in Lausanne somewhat later, during the Seventies. Its refinement and strong relationship with nature evoked associations with breathing and meditative rapture, although some pieces veered towards the vacuously decorative.

By degrees, modern textile art spread across almost all the European countries by means of national or international biennials, with the UK leading the way in offering an excellent university-level system for “studio artists”, as craftspeople were called there. In addition, the international miniature textile art events that commenced in London strongly influenced the development of textile art, and continue to do so today (e.g. “miniartextil” held in Como).

Feminism and textile art

It is a fact that textile art is primarily created by women. This also applies to the exhibitions involving textile art that have come to the fore in the art scene in recent years. The directors of both “Art & Textiles” held in Wolfsburg in October 2013, and of “To open Eyes” held in Bielefeld in November 2013, assured me that textile art had nothing to do with feminism! They probably stated this in an effort take some of the pressure off this art form. They are mistaken; if you listen to the grandes dames of textile art (Claire Zeisler), Lenore Tawney, Sheila Hicks et al.), you will hear that their intention was to do things differently from their male colleagues, and to create something related to themselves and the weaving traditions of their continent. This is clearly evident in the recorded interviews kept in the “Archives of American Art” (http://www.aaa.si.edu/).

Rosemarie Trockel now ranks third in the “Kunstkompass” – the German Manager magazine’s “art compass” providing an art ranking – and her pieces achieve six-figure sums. The darling of the art scene appears to be the only “textile artist” who has carved out a place for herself in the male-dominated art market. Many younger textile artists now aspire to a similar strategy of submitting their work to the principles of the art market; sadly, this is a course of action advised by art colleges and academies.

The post-Lausanne period during the Nineties

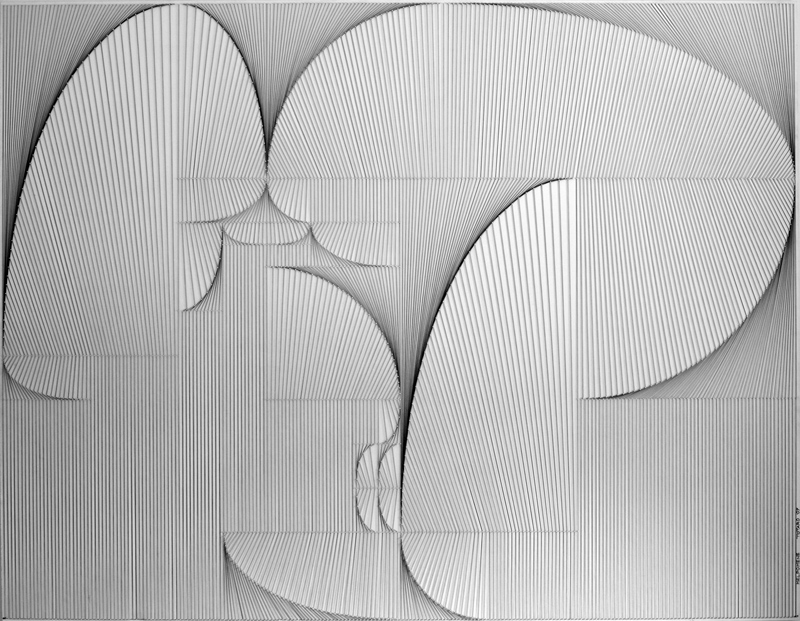

When the Lausanne Biennials reached a dead end (the organisers had been flirting with the idea of turning the event into an art biennial, although this role was already fulfilled by Venice), textile art continued to move forward quietly. Developments included what Michel Thomas (footnote 2) termed “digital textile art” using new materials and technologies (described by Marie O´Mahony and Sarah Braddock et al.) and – the exact opposite – a return to traditional tapestry (e.g. formation of the European Tapestry Network).

The revival of the old jacquard technology using digital media has produced a great many interesting pieces by artists such as Lia Cook and Cynthia Schira from the USA as well as Lise Frølund and Grethe Sørensen from Europe; they constitute textile art in its own right, unlike Gerhard Richter’s jacquard editions in which the design concept and execution are separate processes.

Regrettably, the textile art community broke up into separate movements (patchwork/quilt art, felt art, various weaving groups etc.) that have achieved remarkable success in their individual fields. The formation of the “European Textile Network” in 1991 was consistent with efforts to unite the East and West as well as to counteract the fragmentation of those involved in textile culture.

A Textile Revival in the Art Scene

The art scene functions according to fixed rules managed by a small group of insiders. These guardians of art will not surrender their prerogative of interpretation. According to the “Kunstkompass” (footnote 3), the group is dominated by Anglo-Saxons and Germans, and their inflation of prices is one of the reasons why ordinary museums can no longer afford the sums achieved at art auctions. For the wider public, art has almost assumed the role of religion. Regrettably, this means our culture is in the hands of speculators rather than being defined by democratically appointed groups of people who have the public good at heart.

The art scene has registered an interest in textiles for a number of years (Joanna Mattera, the former editor-in-chief of Fiberarts magazine, sees 2009 as the turning point). The reason behind this is always the same: in our virtual world there is a hunger for tactile items – things that can be touched. Several sources mention Seth Siegelaub’s exhibition, “The Stuff that Matters”, held in London in the spring of 2012 (footnote 4). Originally a member of the art scene, Siegelaub (1941 – 2013) began collecting textiles as well as publications on textiles (footnote 5) and considers the textile medium a primal form of human life.

The Finnish art critic, Hannu Castrén discovered his love of textiles very recently; he speaks of modern art as an “insatiable beast” that will swallow anything.

To avoid the appearance of superficiality, the captions describing pieces in such exhibitions should at least note the techniques employed. In Wolfsburg, the captions for the jacquard tapestries of paintings by Gerhard Richter (no. 1 in the “Kunstkompass”) did not list the workshop where they were woven (Flanders Tapestries in Wielsbeke, Belgium). One of these limited editions were included among the ten most beautiful tapestries in the world listed on the web (footnote 6).

What textile artists can do to increase understanding of their art

An effective strategy may be to place somewhat greater emphasis on content, as is the case in the more challenging textile art exhibitions nowadays, in order to illustrate what is, or could be, good textile art.

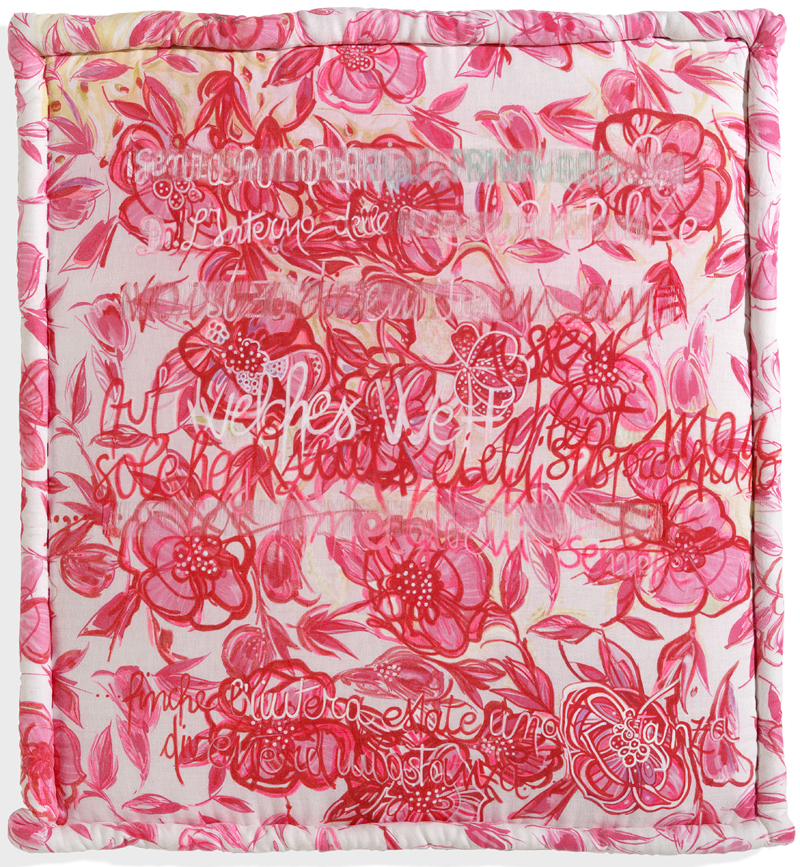

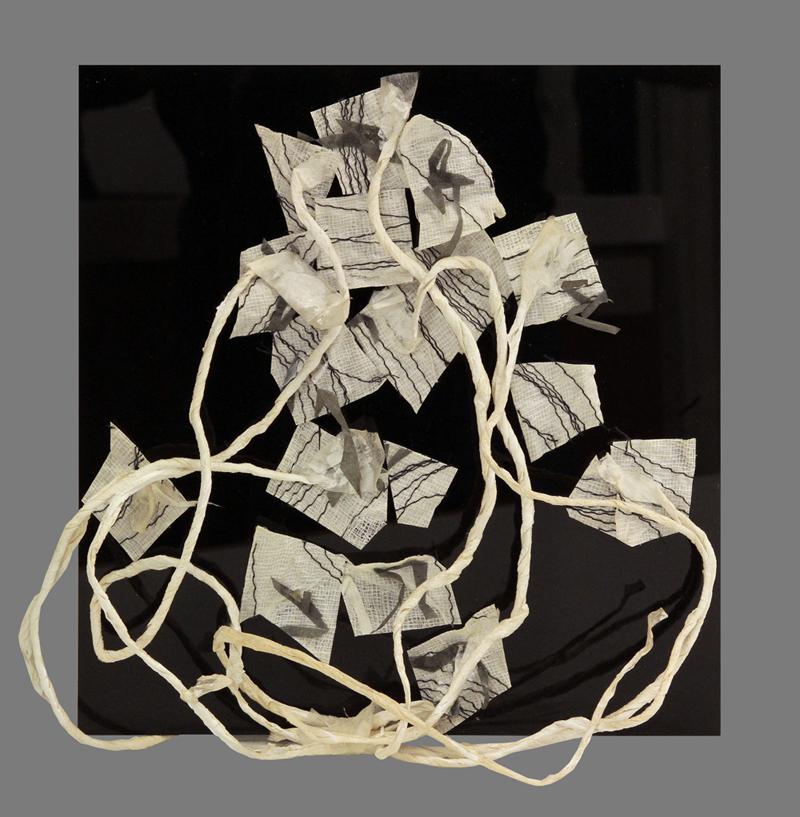

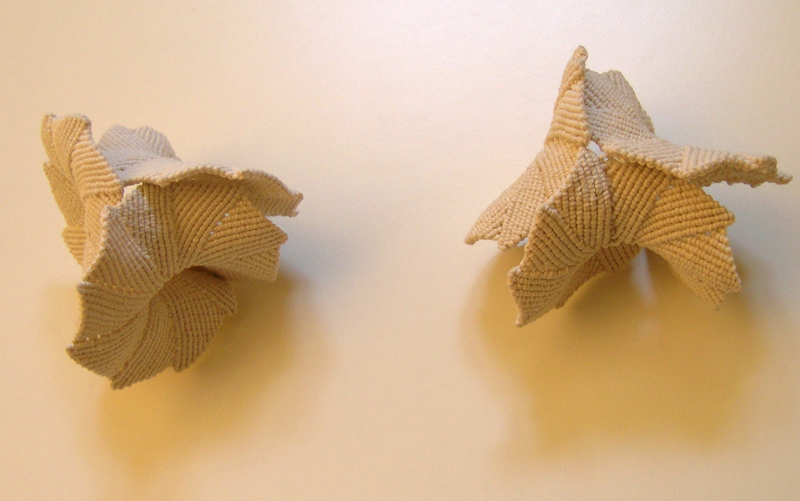

Collectively, the textile artists of each country should endeavour to show their own Modern History of Textile Art in the most important museums of their countries, as they are now doing in Italy. Following “Off the Loom” held in Rome in 2000, this is the second major retrospective featuring the great names of Italian textile art.

It would be wonderful if other European countries were to follow Italy’s example!

Beatrijs Sterk

Hanover, 17th August 2014

Former publisher of Textile Forum magazine and Secretary General of the European Textile Network

Note: This article was written for the exhibition OFF LOOM II to take place from January 23 to April 12, 2015 at the Museo Nazionale delle Arti e delle Tradizione Populari , Piazza Guglielmo Marconi 8/10- I-00144 Rome ; opening January 22 at 18:00 h

Footnote 1: http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-claire-zeisler-12076

Footnote 2: Michel Thomas, Christine Mainguy u. Sophie Pommier, “L’art Textile”, Skira, Genf 1985, ISBN 2-605-00068-0

Footnote 3: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kunstkompass

Footnote 4 :http://www.ravenrow.org/exhibition/the_stuff_that_matters/

Footnote 5: https://www.textile-forum-blog.org/2014/04/bibliographica-textilia-historiae/

Footnote 6: http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140812-the-10-most-beautiful-tapestries