Exhibition update:

Johanna Schütz-Wolff : Expressive Bildteppiche und Grafik, from 12.11.2015 to 28.2.2016 at Museum Starnberger See, Possenhofener Str.5, 82319 Starnberg, Germany, opening time: Tu. – Su. 10 – 17 h

For September 2016 an exhibition with the work of Johanna Schütz-Wolff is planned at Castle Willigrad near Schwerin, Germany

Exhibition from 21st May to 20th September 2015 at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst,

Johannisplatz, Leipzig

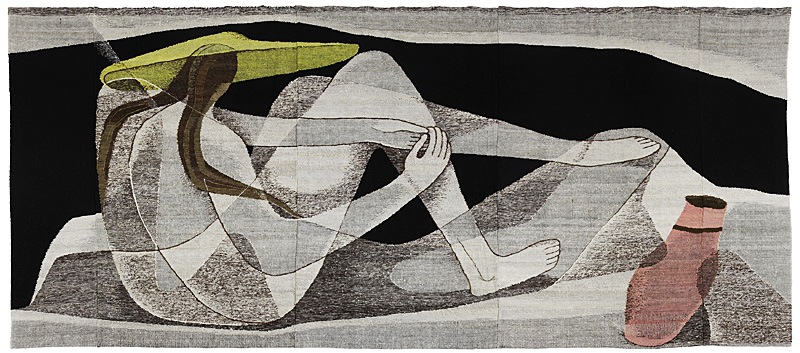

Johanna Schütz-Wolff is one of the artists unjustly ignored by history, despite the fact that she enjoyed greater initial success than, say, Anni Albers or Gunta Stölzl. Her wall hanging, “Die Liegende (Recumbent Woman)” was awarded a silver medal at the 1928 “Deutsche Kunst (German Art)” exhibition held at the Düsseldorf Kunstpalast. In late 1929 she participated in the “Moderne Bildwirkereien (Modern Tapestries)” exhibition organised by gallery director and art historian Ludwig Grote at Kunstverein Dessau, with the aim of “leading tapestries out of their exile in the applied arts”. The exhibition later toured nine German cities, displaying tapestries by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Hans Arp, Wenzel Hablik, Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl. Johanna Schütz-Wolff’s work left the greatest artistic impression on Ludwig Grote. Her male nude became a sensation!

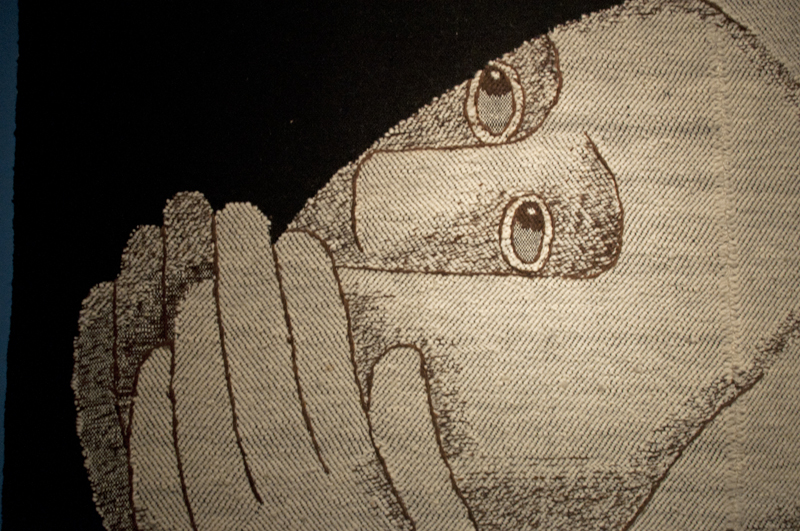

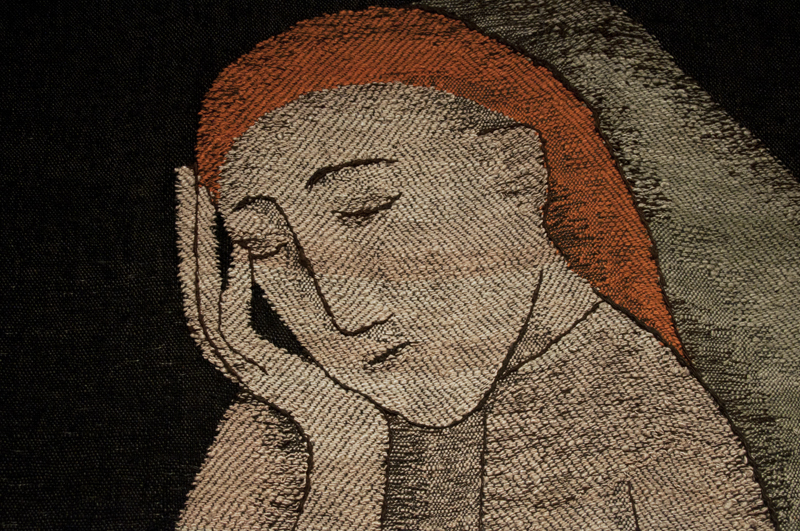

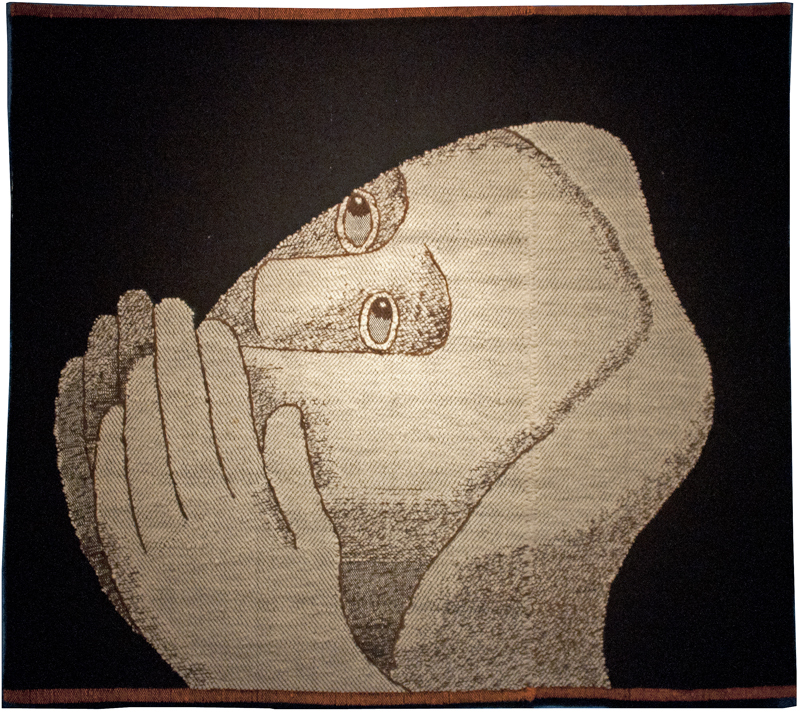

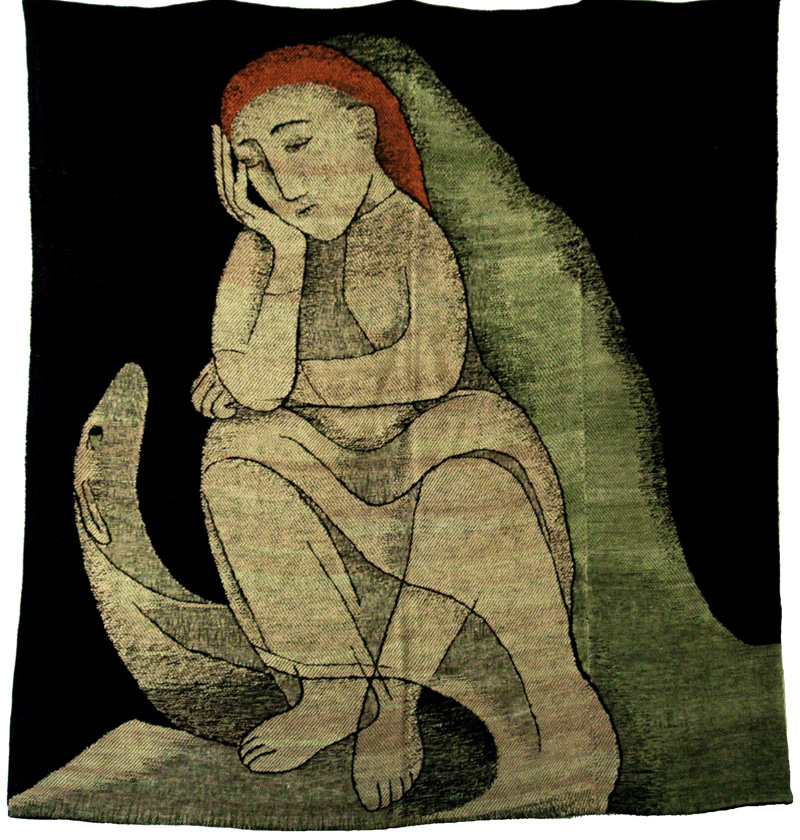

An illustration of the artist’s ideas on tapestry weaving, it was produced in an open weave that revealed both the warp and weft, with the highly abstract figure appearing in hand-spun and plant-dyed wool. The only two weaves she employed were tabby and twill, and rather than using a cartoon she merely placed a drawing of the major lines under the warp of her horizontal loom. This type of tapestry weaving is known as the semi-gobelin technique. Johanna Schütz-Wolff rejected French gobelin weaving which she considered “the bastard of painting”. The artist made impressive use of new stylistic devices, opening the warp and making crossed threads visible to show the act of weaving. The same ideas – truth to materials and authenticity – were espoused both by the Dessau Bauhaus and the Burg Giebichenstein School of Art and Design in Halle, where Johanna Schütz-Wolff taught the textile course and established the weaving department from 1920 to 1925. Those educational institutions were considered two of the best in the country. Bauhaus emphasised a unification of the arts and crafts in architecture and industry, while Burg Giebichenstein gave greater prominence to an integration of the crafts and arts in the spirit of the German Werkbund (form follows function). Bauhaus was dissolved because it was felt to be too progressive by the National Socialist rulers. Burg Giebichenstein continued to exist but was greatly restricted, and gradually fell into oblivion until the Berlin Wall came down. Although great artists worked there in the post-war period, nothing of East German origin would ever be considered important in West Germany in that time.

Anni Albers’ success was largely achieved in the USA, probably not least because her husband Josef Albers was a well-known painter. Gunta Stözl had been forced to move to Switzerland and was unable to repeat her earlier success. Internationally she was only rediscovered much later, and her work is currently the subject of a second international revival, as it were, in the social media and elsewhere.

Johanna Schütz-Wolff was effectively banned from practising her profession by the Nazi rulers, since she did not receive any invitations to participate in exhibitions as of 1933. There were no acquisitions of her work, and she was passed over in competitions where she used to excel. Furthermore, the then “Reichsfachschaftsleiterin” (leader of the Reich’s professional association) – weaver Alen Müller-Hellwig – was no longer permitted to allocate materials to her. What was it that the Nazis disliked about her work? It has to be understood that those rulers – probably like those in any totalitarian regime – had a very limited and highly conservative appreciation of art. Johanna Schütz-Wolff’s work was misread as “deliberately primitive” and thus rejected. She was annoyed about the kitsch of the period: “Oh the ignorance, the amateurishness, the stupidity”. When her husband’s book, “Der Anti-Christus (The Antichrist)” was banned and there was a risk of the couple’s house being searched, Johanna Schütz-Wolff cut up and burned thirteen of her early tapestries that constituted an essential part of her work. In 1937 at the Magdeburg Museum, one of her pieces “Teppich mit 9 Felder” was “Degenerate Art”, proving that her fears were not unfounded. Effectively, she was left with the church as her only client. Working at home in cramped conditions and without proper materials, she nevertheless created pieces such as “Trost des Engels (The Angel’s Consolation)”, a large-format tapestry that provides no clue of the laborious process in which it was created.

Wolle, Leinen- und Köperbindung, gestickte Konturen (wool, tabby and twill, embroidered contours) ; Schenkung aus dem Nachlass der Künstlerin (gift from the estate of the artist) , 2010 GRASSI Museum für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig

photo: Christoph Sandig, Leipzig

Johanna Schütz-Wolff met with renewed appreciation after the war, creating large textile commissions such as “Frau vor Landschaft (Woman before a Landscape)” and metal wall objects for the Hamburg state horticultural show. However, she did not achieve recognition on an international level. In her feature on the exhibition to mark the 100th anniversary of Johanna Schütz-Wolff’s birthday, published in Textile Forum 2/1996, art historian Eva Mahn of Weimar mentioned “Exaggerated attention given to the Bauhaus and a concentration on constructivism and abstract painting”, and “Despite the fact that she created numerous carpets of exceptional quality in the post-war period, Johanna Schütz-Wolff belongs to a forgotten generation”.

It is said that textile artists do not begin to be famous until fifty years after their death; this is right on target in this case, as the exhibition was produced to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the artist’s death and the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design in Halle. It presents some 20 large-format wall tapestries in conjunction with selected graphic work and architectural projects. The show has been assembled with great care, and I would recommend anyone to take the opportunity to visit this great exhibition before it closes on 20th September 2015. I was disappointed to find that a new catalogue is not available, and visitors must make do with the 1996 publication, which is very well produced (Johanna Schütz-Wolff, Textil und Grafik zum 100. Geburtstag; edited by Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg, 1996, 135 pages, 55 black-and-white and 58 colour illustrations, ISBN 3-86105-131-1, German text; www.burg-halle.de). It is available at 30 Euro at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst.

As a final comment, I wonder where German and international textile art would be today if the “Thousand-Year Reich” had never existed. The new weaving principles established in those days did not see a revival until the 1960s, emerging again in the USA: the principles of artists weaving their own work; pieces being true to the materials employed and authentic; and, in addition, the power of experimentation and abstract design. Today this is considered the beginning of weaving as an art form in its own right. However, there are forgotten precursors among whom Johanna Schütz-Wolff is probably one of the most important names.

Beatrijs Sterk, 30 August, 2015

All exhibition and detail photos are made by Beatrijs Sterk, the complete tapestry images are press photos!

.