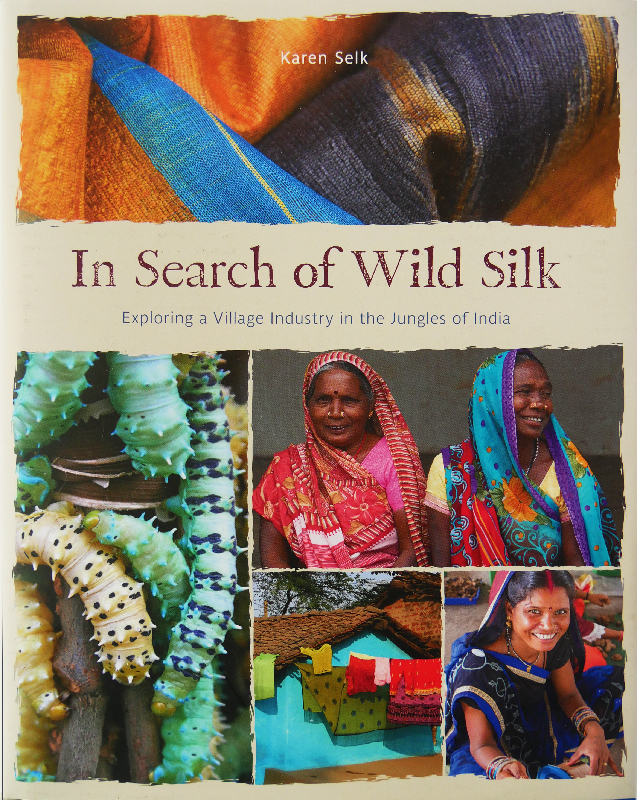

In Search of Wild Silk – Exploring a Silk Industry in the Jungles of India, Karen Selk, Schiffer Publishing, 2023, 270 pages, 308 colour photos, 10 maps and drawings,

ISBN 978-0-7643-6497-6, price US $ 39.99 ( Amazon Euro 39.35)

Karen Selk is a weaver who became interested in wild silk during the seventies. Intrigued by this beautiful material, she and her friend Michelle Whipplinger started to travel to Asia in search of wild silk, especially to India, where silk used to be and still is supported by the government as a source of income for indigenous people. Her approach was completely in line with the spirit of the time – choosing a lifestyle of artistic freedom, then turning it into a way of earning a living by importing beautiful hand-raised wild silk from India and selling it to other weavers and artists. Karen Selk and her husband Terry Nelson would sell dyed yarns and fibers. This book tells the story of how Karen and Michelle started their search for wild silk and what they found out about it. Michelle Whipplinger became known for her activities in natural dyes under her Earthues label and for her publication of a journal called Color Trends. I remember her from a small hand-written book about natural dyes that I received some time in the eighties.

Karen Selk and her husband started a company called Treenway Silks which they managed for over 30 years. It is still in existence, but now has a new owner who is still in close contact with the founders. Nowadays the company also sells natural dyed yarns. The book came into being after Karen’s retirement from the business, a time for rethinking and expressing gratitude for all the wonderful people she had come to know who had given her advice and made her the expert in wild silk she now is. She herself has given courses and talks on weaving and silk fusion. For over 10 years she led travel group to India in search of wild silk!

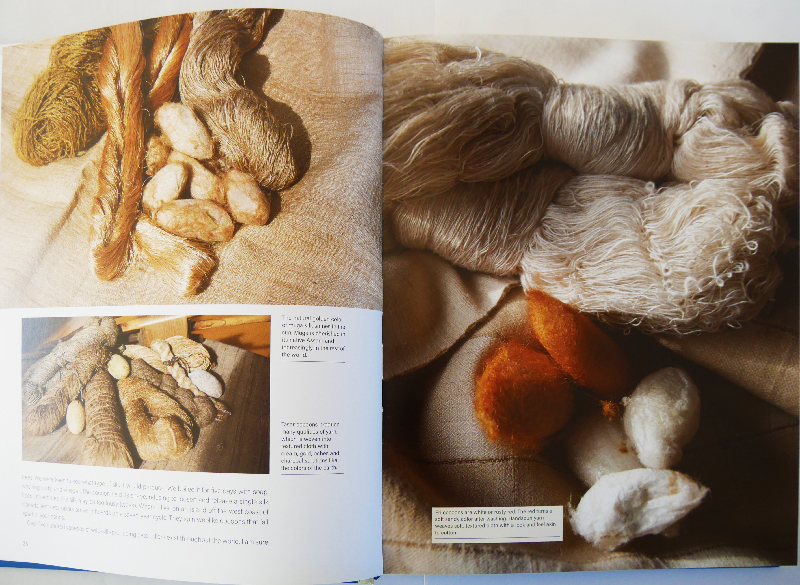

The book highlights many facts about wild silk, with photos, maps and drawings indicating the places where wild silkworm cultivation could and still can be found in India; the way wild silk is produced, some of it reeled but some also spun like cotton from the cocoons where the pupae hatched into silk moths. Three species are described in detail, Tasar, Muga and Eri. Among these species, the gold-coloured Muga silk is only raised in Assam, India; grey and beige Tasar silk is more wide-spread and appears to be the most productive species; and the white or brick-red Eri silk does not yield a continuous filament, but is spun from the combed cocoons. Weaving one sari weighing about 550 grammes requires 2000 cocoons of Tasar silk, 2,500 cocoons of Muga silk or 1,250 cocoons of Eri silk. The silk worms are raised outside, for example by collecting the eggs, bringing the worms to a new tree with fresh leaves, and defending them against predators.

It is interesting to read the diary entries that are spread throughout the book, dating from October 1988 to November 2019. They include heart-warming stories about the silk worm farmers, the spinners and weavers of wild silk, their villages and skills. Wild silk is a little-known industry that provides a sustainable income, allowing families and communities to stay together while preserving their way of life.

This extraordinary book sums up the achievements of over 30 years of involvement in wild silk in India. It ends with a four-page glossary of textile and silk terms, a list of resources regarding the revival of wild silk, a five-page bibliography and an index. It is recommended reading for anyone interested in the subject. I would advocate purchasing this beautiful book written by an author who dedicated her life to the subject.