Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art

Exhibition from 14 September 2024 to 5 January 2025 at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

This was the second venue of this important exhibition which began at the Barbican Centre, London, showing from 13 February to 26 May 2024. After visiting the Amsterdam venue I was slightly disappointed, in spite of seeing the works of many great artists. This was due to the exhibition‘s focus on power and politics, which gave me the impression that textile art is still perceived with reservations by fine art curators unless it expresses rebellion or protest against social injustice. If textile art were fully accepted, there would be no need for special themes relating to politics or other trendy subjects. The highly successful retrospective exhibitions on Sheila Hicks in Düsseldorf/Bottrop and on Olga de Amaral in Paris are convincing art exhibitions without any special theme.

The curators of “Unravel” had asked themselves: “What does it mean to imagine a needle, a loom or a garment as a tool of resistance? How can textiles unpack, question, unspool, unravel, and therefore reimagine the world around us?” The curators did understand that “the medium has been historically undervalued within the hierarchies of Western art history. Textiles have been considered ‘craft’ in opposition to definitions of ‘fine art’, gendered as feminine and marginalised by scholars and the art market.” The organisers wanted to show over 40 international artists challenging these labels. “They harness the medium to speak powerfully about personal everyday stories and explore broader social and political issues… these artists defy traditional expectations of textiles… they draw on its material history to reveal ideas relating to gender, labour, value, and ecology, while also showing ancestral knowledge, and histories of oppression, extraction and trade that are often intertwined with textiles…”

“Rather than dictating a chronological history of textile art, the exhibition is organised in thematic dialogues between artists – across generations and geographies – to explore how artists have embraced textiles to critique or challenge regimes of power.”

There were six categories grouping the works; many of the artist’s names in these categories were interchangeable, making the classification not very precise, and the overall impression was that of an outsider art form that had its appearance on the art market thanks to provocative works. If textile art had really attained recognition, why this focus on power and politics?

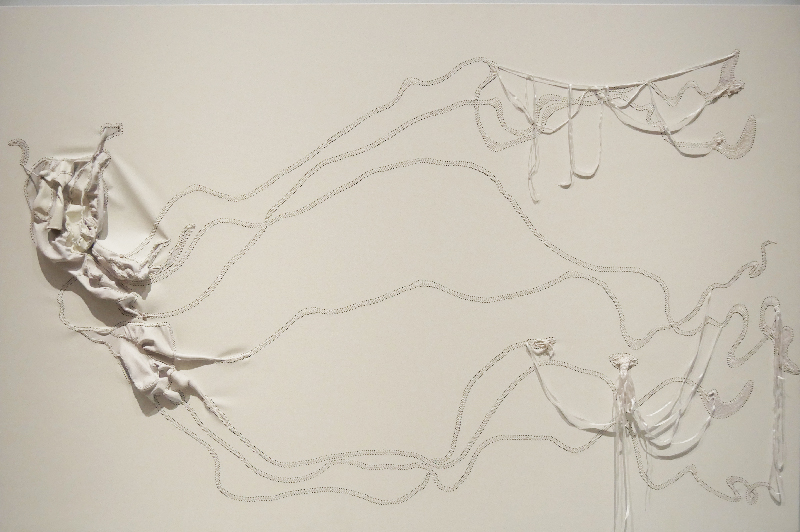

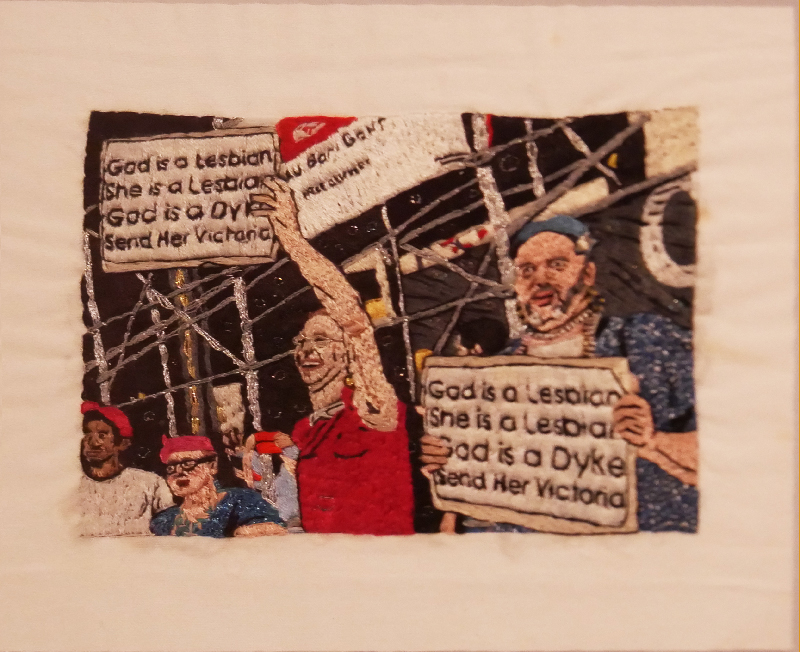

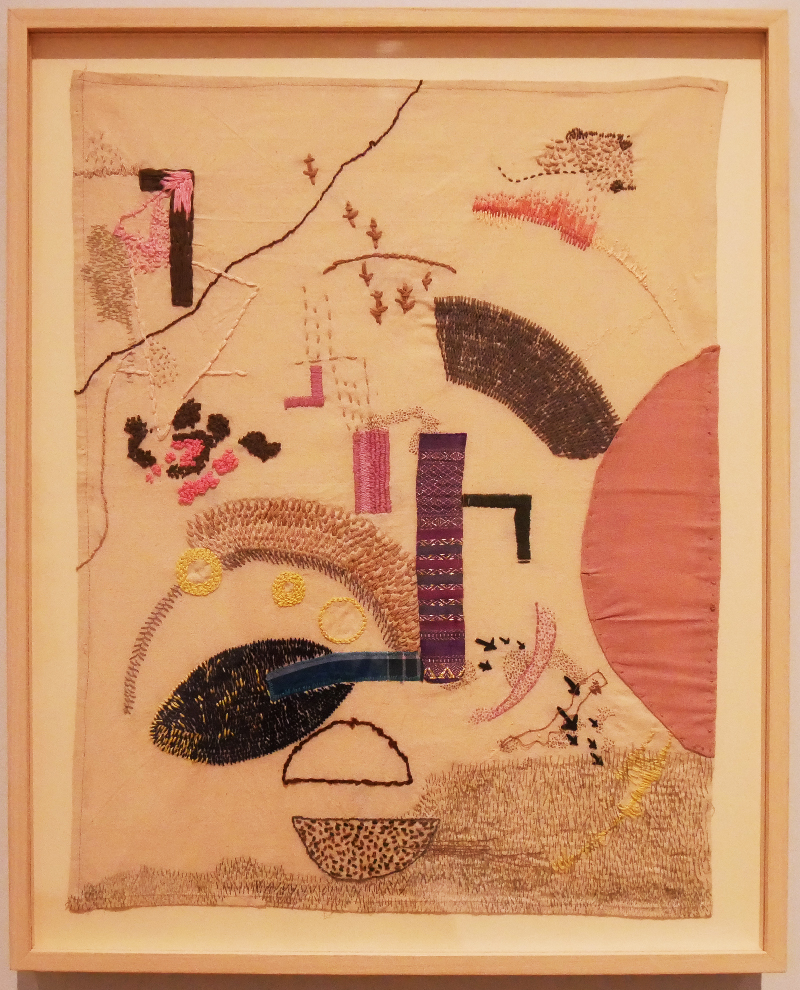

1. “Subversive Stitch” for the use of textiles as vehicles for embodied liberation, perseverance and even protest (includes Judy Chicago, Tracey Emin, Ghada Amer)

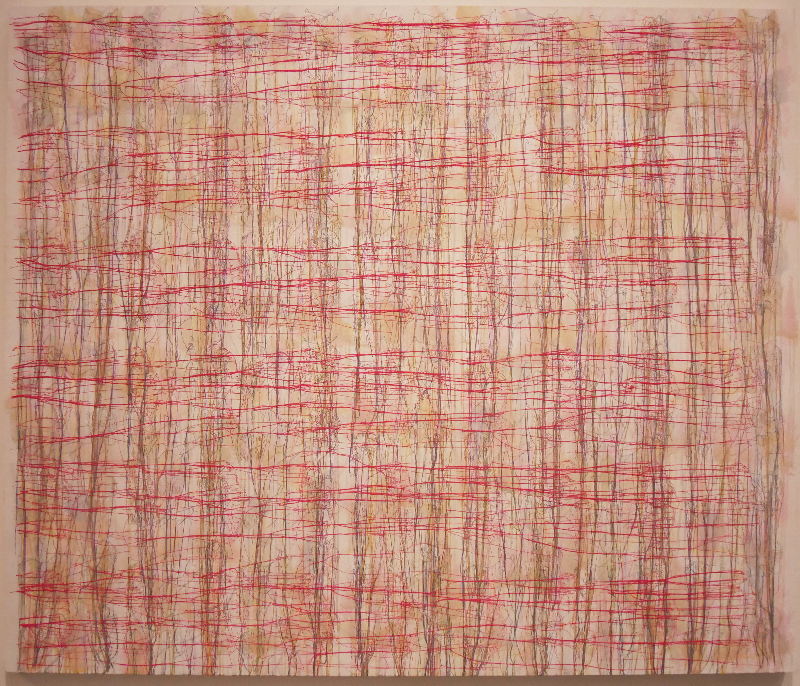

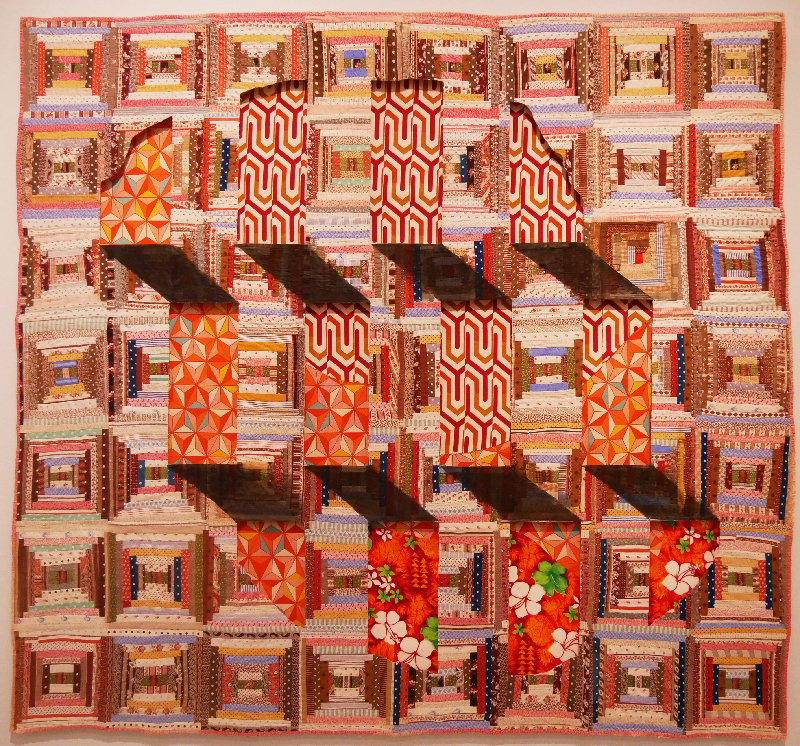

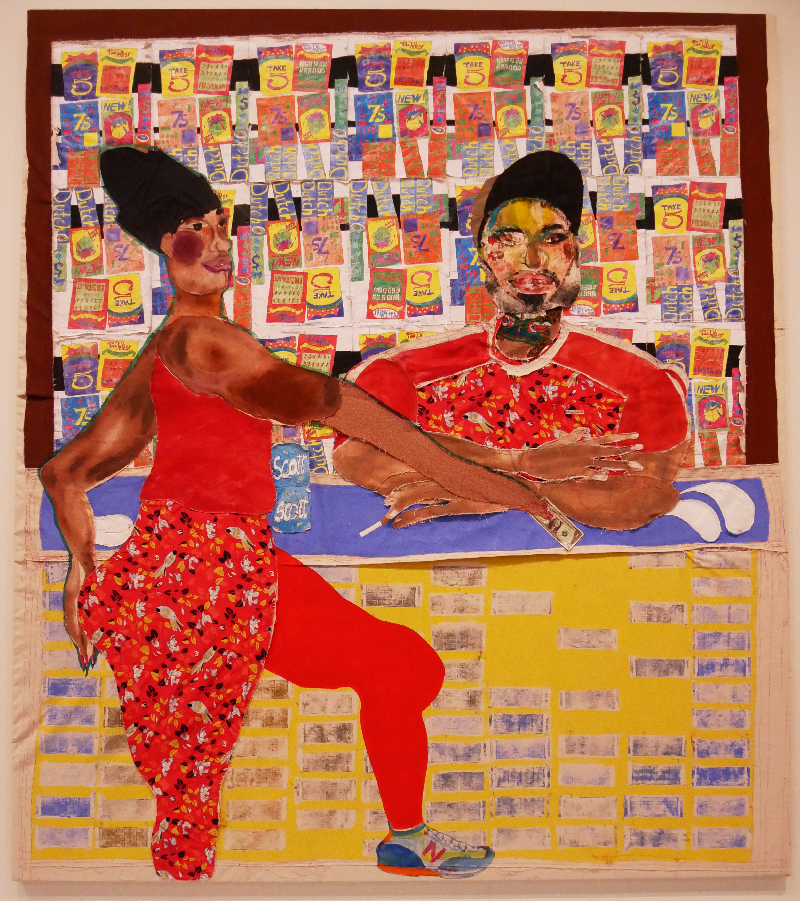

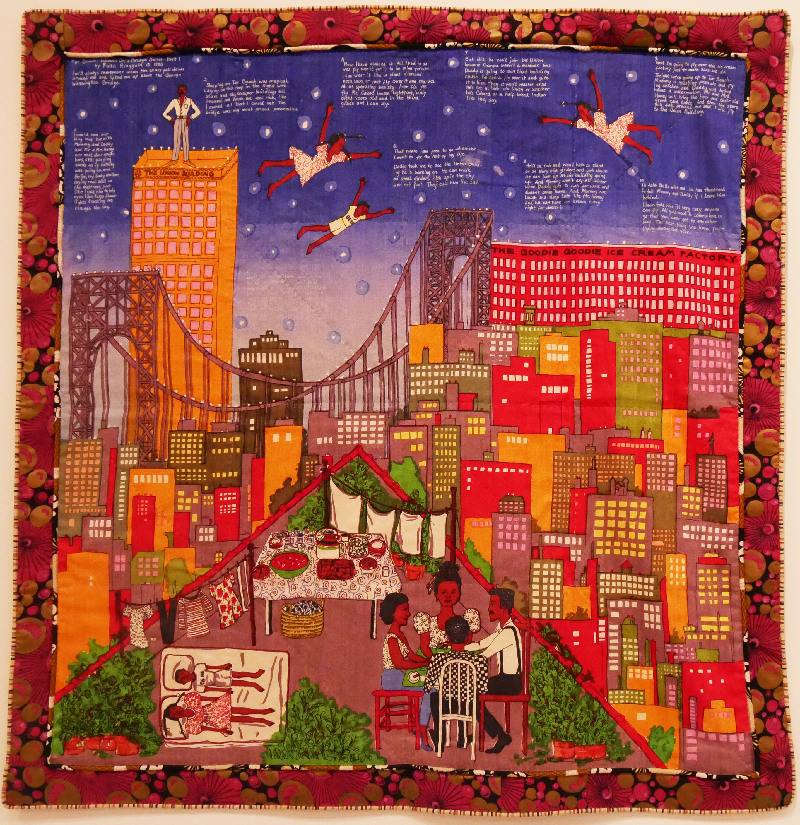

2. “Fabric of Everyday life“ (includes Sheila Hicks, Faith Ringgold, Malgorzata Mirga-Tas)

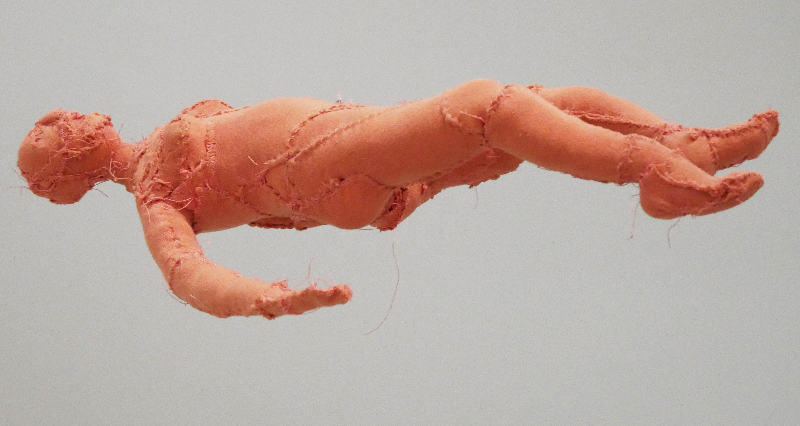

3. “Wound and Repair” suggesting the healing potential of working with fabric and thread (includes Louise Bourgeois, Diedrick Brackens, Harmony Hammond)

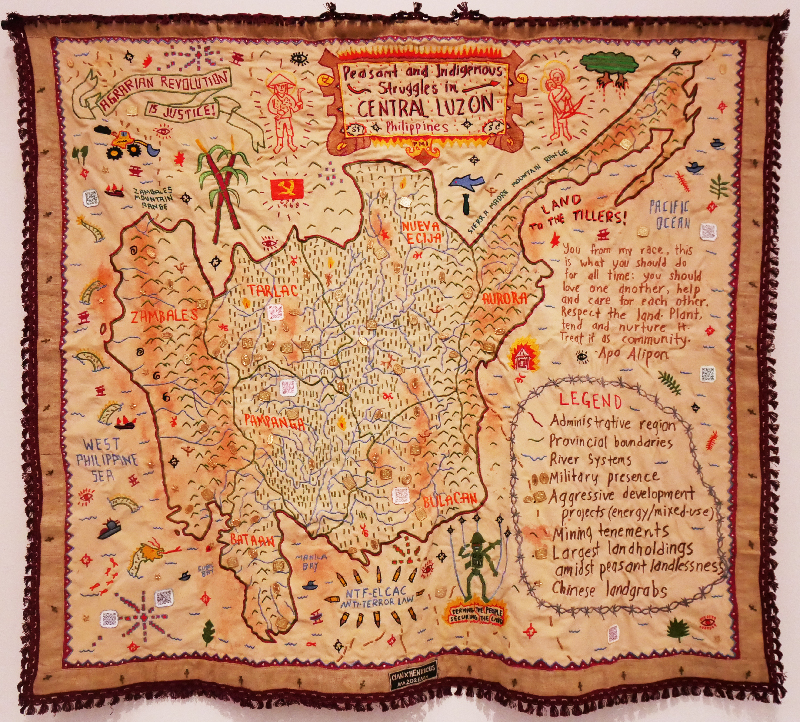

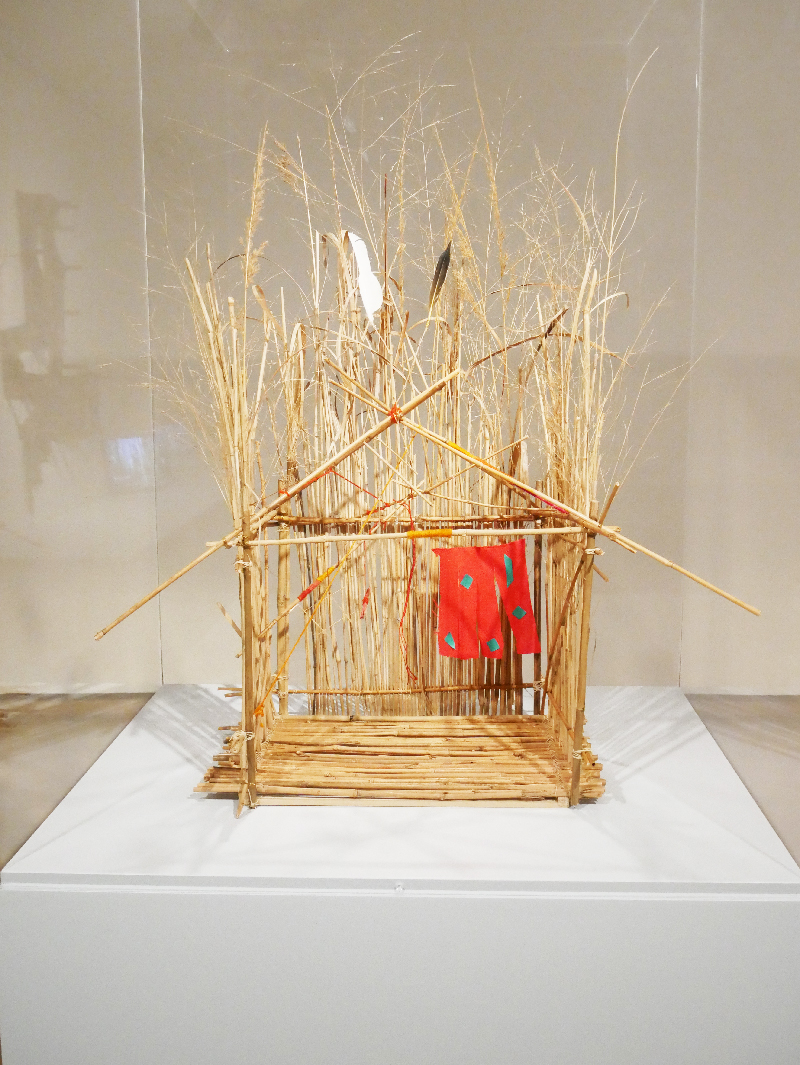

4. “Borderlands”; instead of a boundary, borderlands can be sites for profound creativity (includes Kimsooja, T. Vinoja, Cian Dayrit)

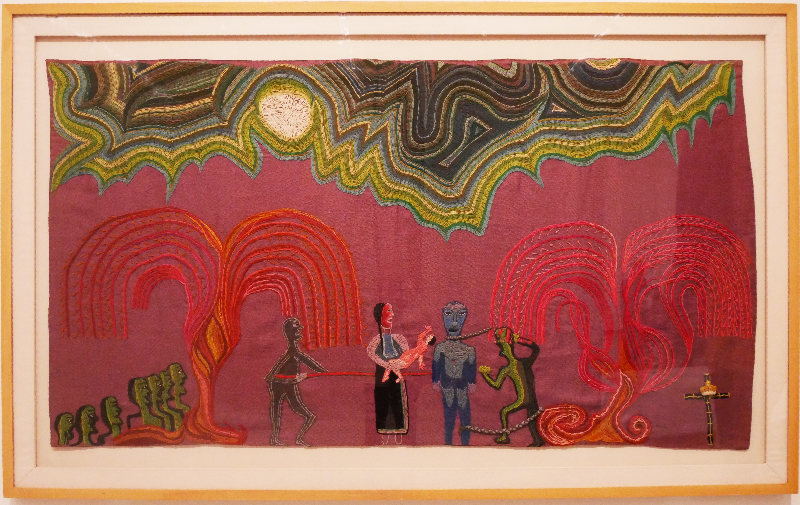

5. “Bearing Witness”; using textiles to document or protest against political violence (includes the anonymous “Arpilleristas” from Chile, Hannah Ryggen, Violeta Parra)

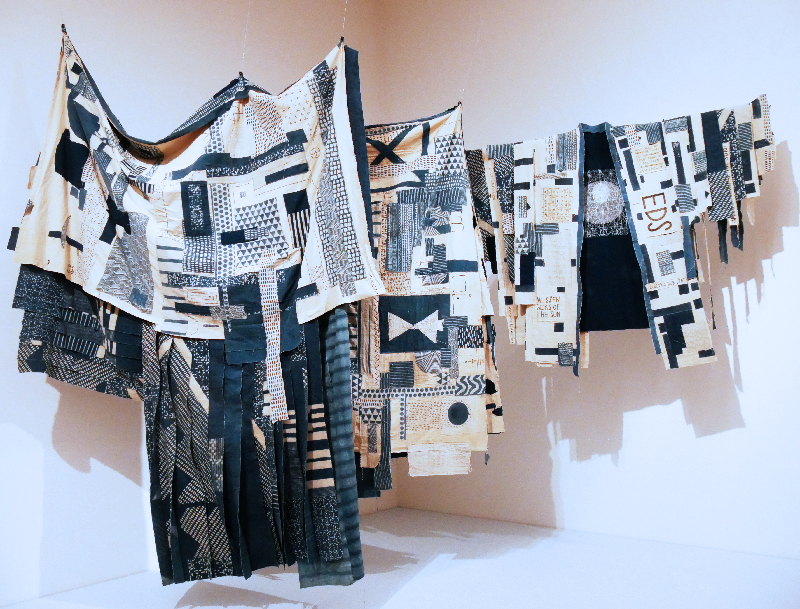

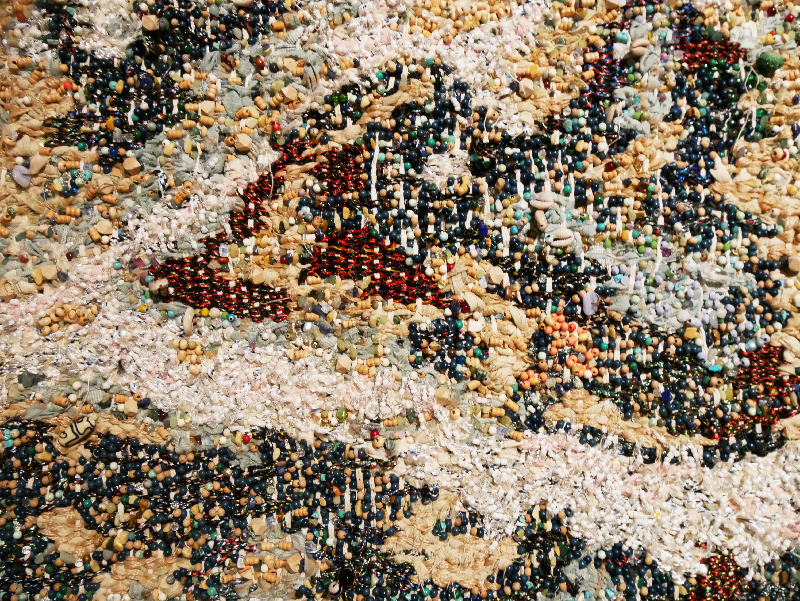

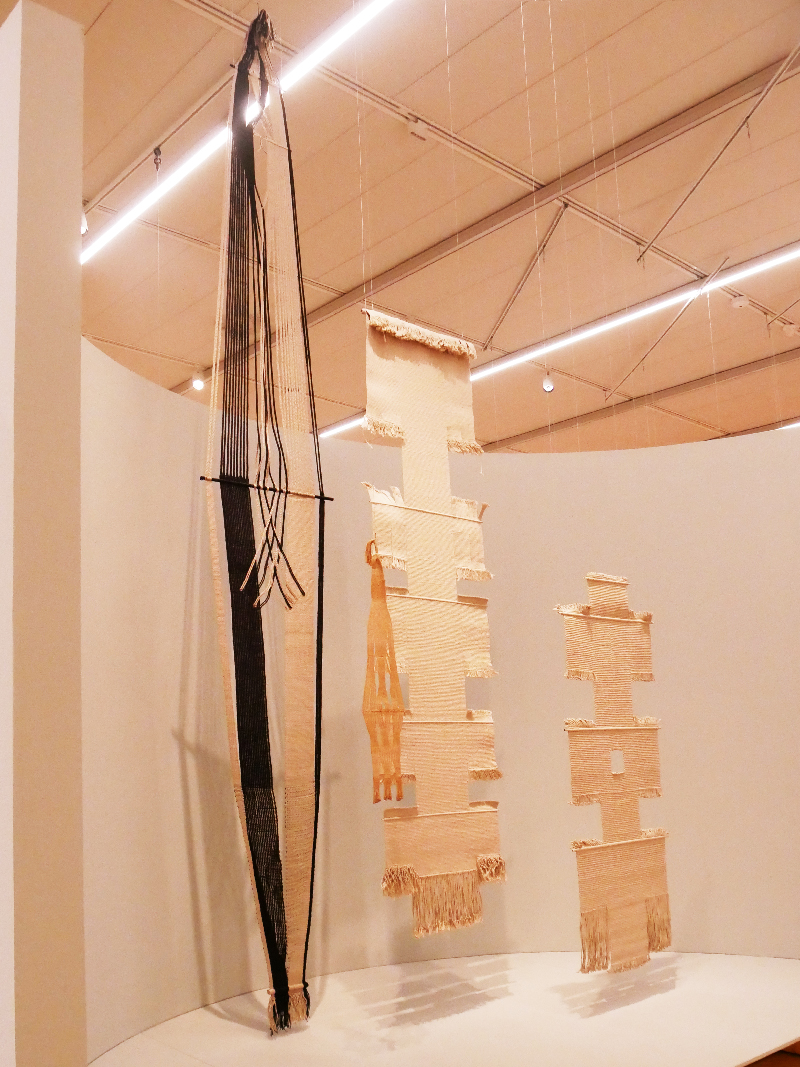

6. “Ancestral Threads”; these artists reclaim, relearn and summon ancient techniques and materials to communicate in new ways today (includes Magdalena Abakanowicz, Yee I-Lann, Tau Lewis)

The Second Textile Revolution

The sheer number of important textile-related exhibitions in 2024, such as the Sheila Hicks retrospective exhibitions at the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf and the Josef Albers Museum in Bottrop, “Woven Histories – Textiles and Modern Abstraction” at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the “Olga de Amaral” exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, brought to mind the notion of a second textile revolution. I may have already mentioned in my blog that this is one of the possible titles of a new book on textile art that I am planning, if I ever find the time. Now that textiles have such a strong presence in important international museums and magazines, other fine art activists take note of what is happening, ten years after it began: Elizabeth Markevitch, from ikono.tv Berlin, states in her Instagram account that 2024 has been the year for textile art: “Once dismissed as ‘craft’ or ‘women’s work’, fibre art has emerged as the world’s newest obsession… not just a trend, it is a revolution… art history is being rewritten.” In her view, “the exhibition ‘Unravel’ demonstrates that textiles can weave powerful political statements.”

It is rewarding to see that more and more professionals from the cultural sector are finally aware of this second textile revolution which began in 2014, and has been documented in my blog over the past ten years. (The first took place in the early 1960s at the Lausanne Biennial.)

What could be seen at Unravel?

There were the great names in textile art, like Magdalena Abakanowicz, Cecilia Vicuña, Hannah Ryggen, Faith Ringgold, Sheila Hicks, Jagoda Buić, Lenore Tawney and many others. I felt that their number should have included Olga de Amaral who, until her Paris show, was mainly known among textile professionals.

Cecilia Vicuña`s work was only moderately impressive; she had a whole extra wall for herself which she had covered in very small works that created an unfinished look. Then again, her large piece on display at the exhibition entrance worked well.

Next there were great names from fine art: Louise Bourgeois, Judy Chicago who (as far as I know) never touched a needle herself, Tracey Emin and Ghada Amer.

It was obvious that fine art curators are aware of artists who have participated in the Venice Art Biennial, such as Malgorzata Mirga-Tas, Igshaan Adams, Myrlande Constant, Jeffrey Gibson, Tau Lewis, Pacita Abad, Antonio Jose Guzman and a few others.

I was not happy with some pieces that were badly made, for instance the works by Feliciano Centurion (collage), Tschabalala Self (collage), Jose Leonilson (embroidery), Georgina Maxime (dress) and Kevin Beasley (audio-visual), but that is always a problem when fine art curators select pieces. They are not concerned with the quality of the workmanship, but only place emphasis on the idea that is expressed. It was Jack Lenor Larsen, the advocate of textile art, who looked for works that had presence, and in most cases they were very well made.

There were nine works from the Stedelijk Museum’s own collection, but unfortunately no Dutch artist was represented in the exhibition. This is another problem of curating; I know from the “Textiles in the Stedelijk” catalogue (ca. 1990) that there are Dutch textile works in the collection (for example, pieces by Anna Verwey, Herman Scholten, Margot Rolf, Marian Bijlenga and many more), but it would appear that more recent acquisitions are not by Dutch artists? And if there are any recent Dutch textile works, why were these not included in this important exhibition?

Some pieces were shown in London but not in Amsterdam, such as “Boy on a Globe” by Yinka Shonibare and “Hammock” by Solange Pessoa. It was unclear why they were not exhibited at both venues.

My conclusion is that we have reached a point in time where textiles as an art genre have gained visibility in important museums, and textile artists are finally receiving the recognition they deserve. It would be a great next step if some curators/organisers were to specialise in textile art so as to appreciate textiles more fully, both in terms of their the artistic value and the material and technical excellence of these artworks.

The catalogue was too heavy (some 2 kg) for me to take home. It is published by Prestel Verlag and sells for circa €45 on Amazon. It includes photos of all the works which are organised according to six categories mentioned earlier.

Beatrijs Sterk, January 2025