Lia Cook´s exhibition, “Inner Traces” took place from 11 September to 16 November 2018 at the Richmond Art Center in Richmond, California.

The works were selected by guest curator Inez Brooks-Myers who did a very good job both in selecting the pieces and in hanging them in the gallery, allowing enough space for each piece to develop its own atmosphere.

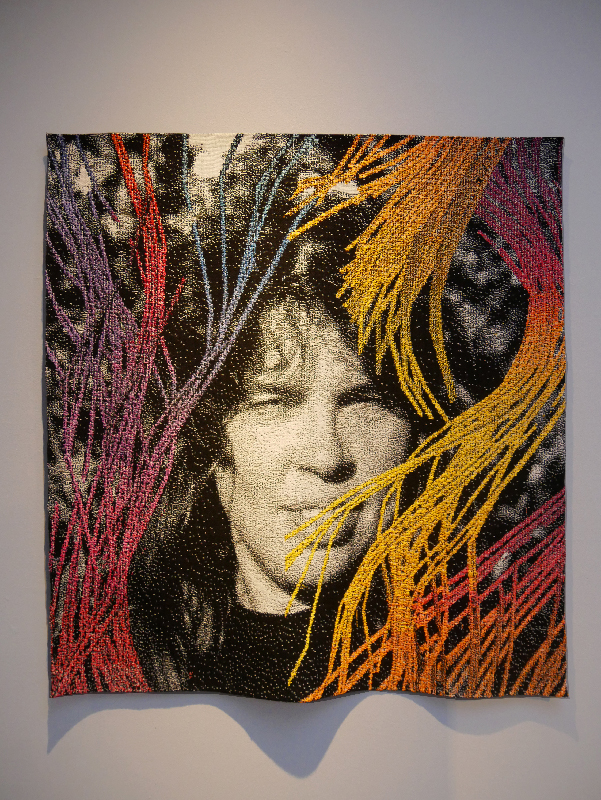

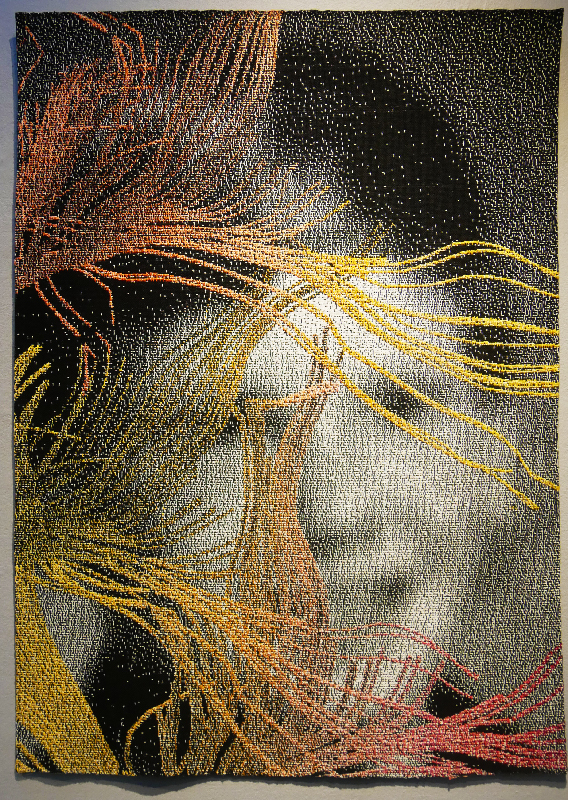

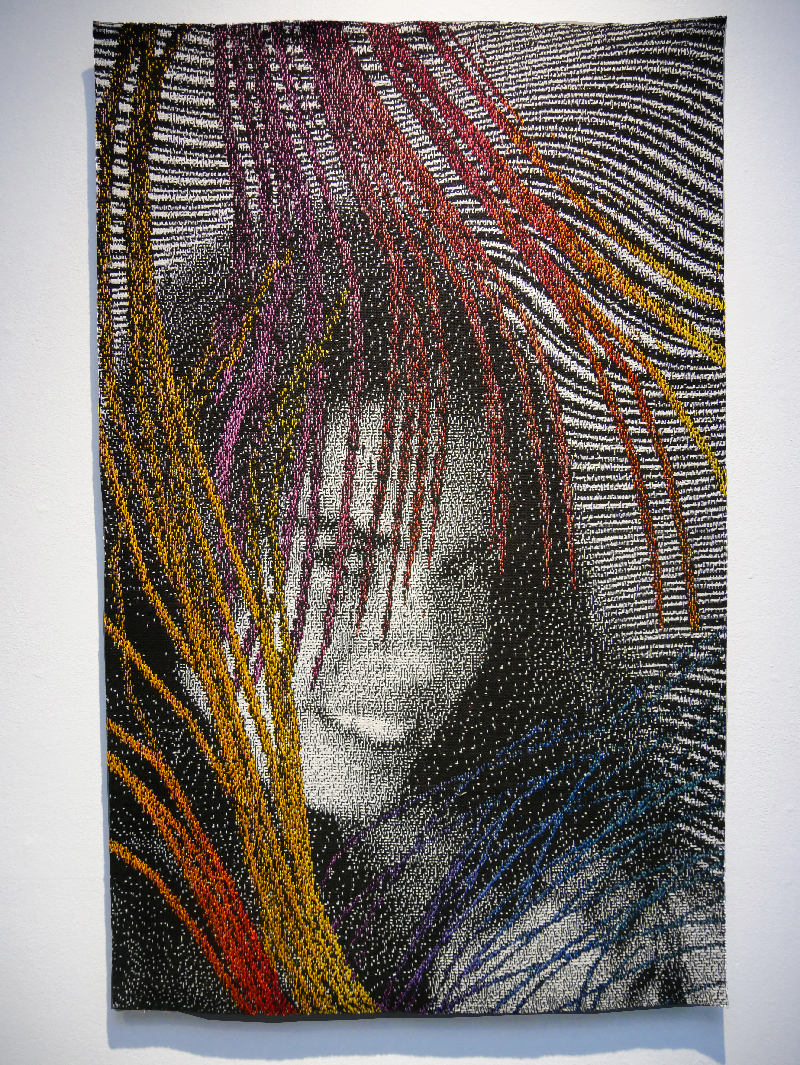

Most of the exhibits were selected from Cook’s recent work made in the past decade; they included many large-format portraits of her younger self as well as portraits of family members, children, dolls and a portrait of a young Dr Timothy Ellmore, one of the neurologists she now works with (1).

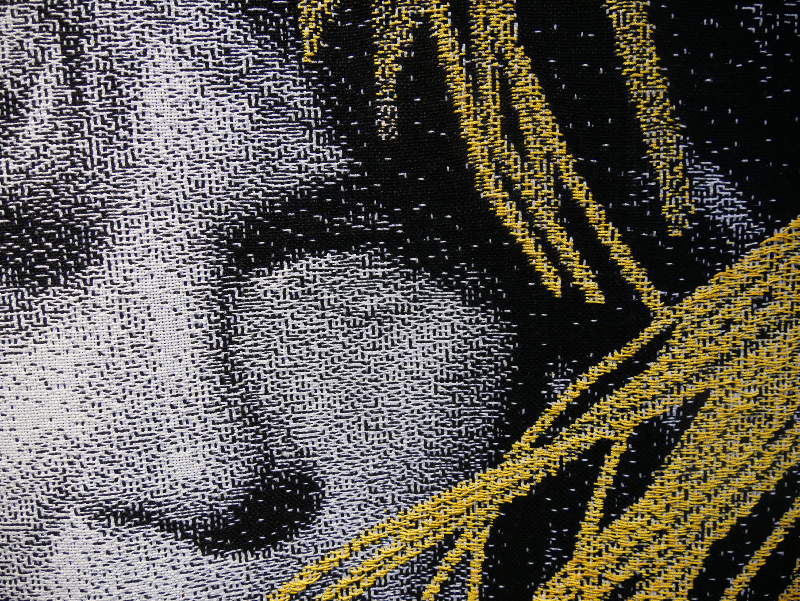

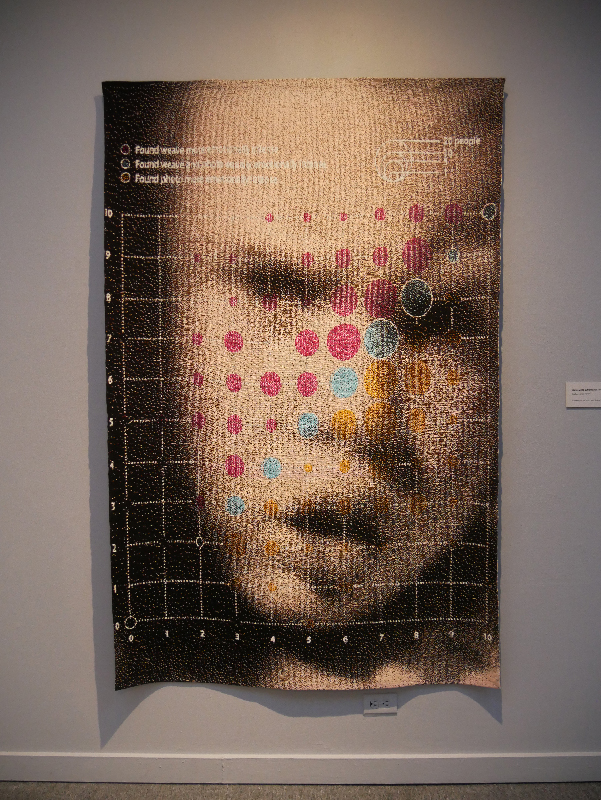

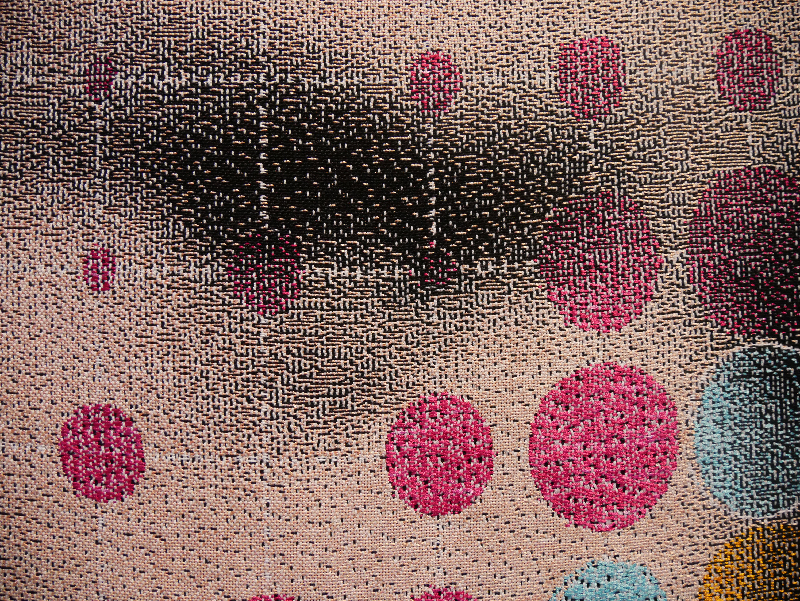

The research Lia Cook is conducting in her collaboration with neuroscientists focuses on emotional responses to paper images versus woven ones. It revealed that different areas of the brain are activated by textile surfaces compared to the same image on paper.

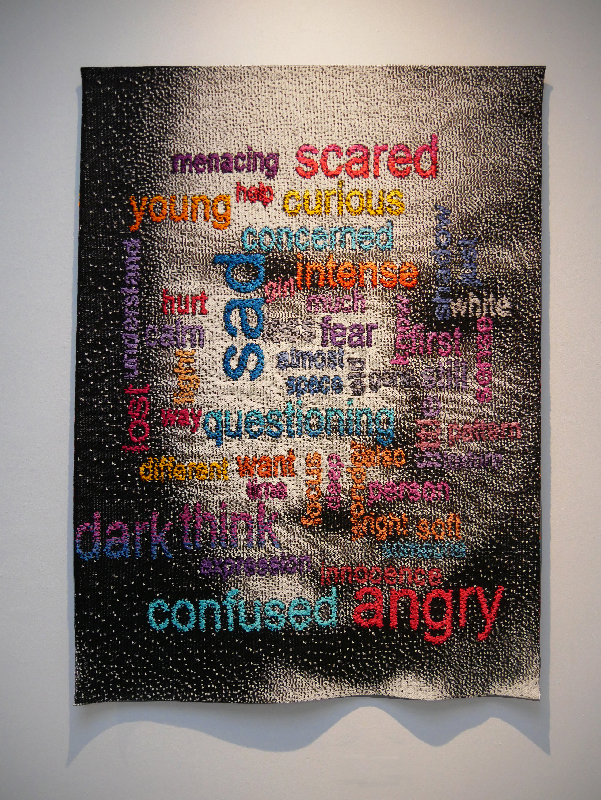

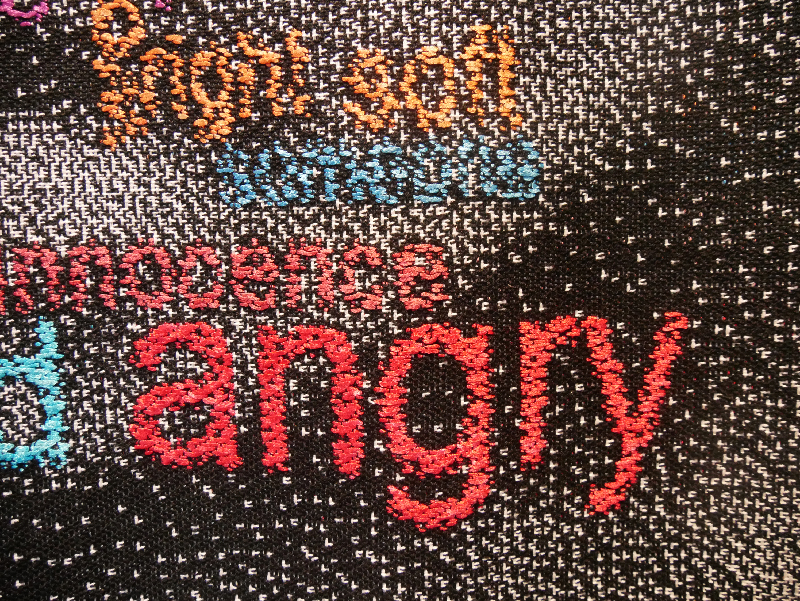

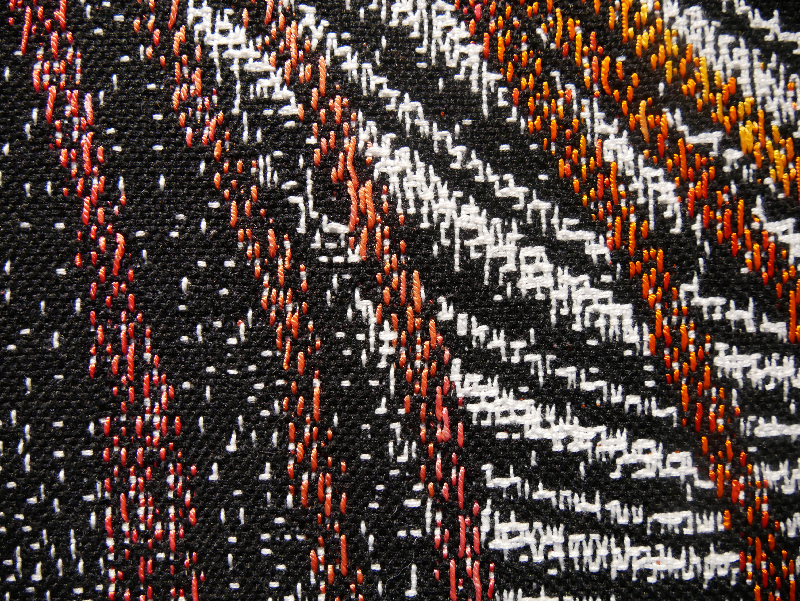

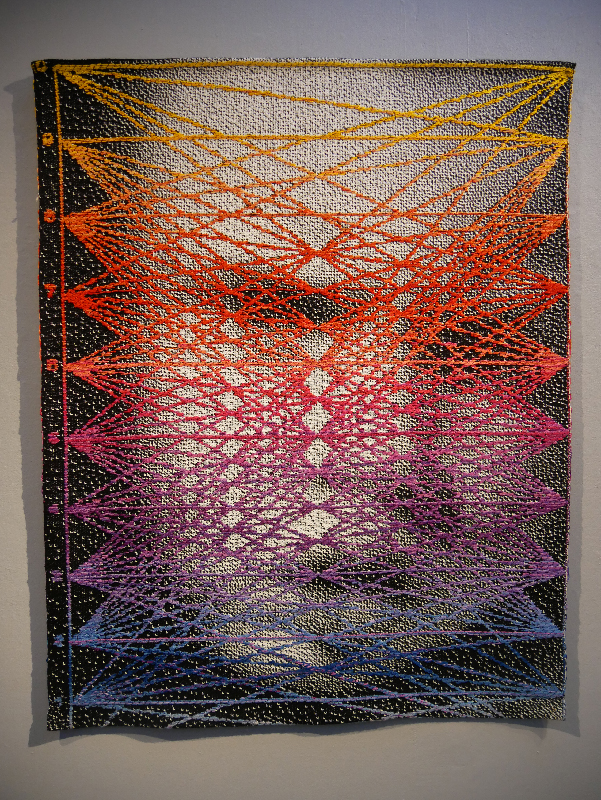

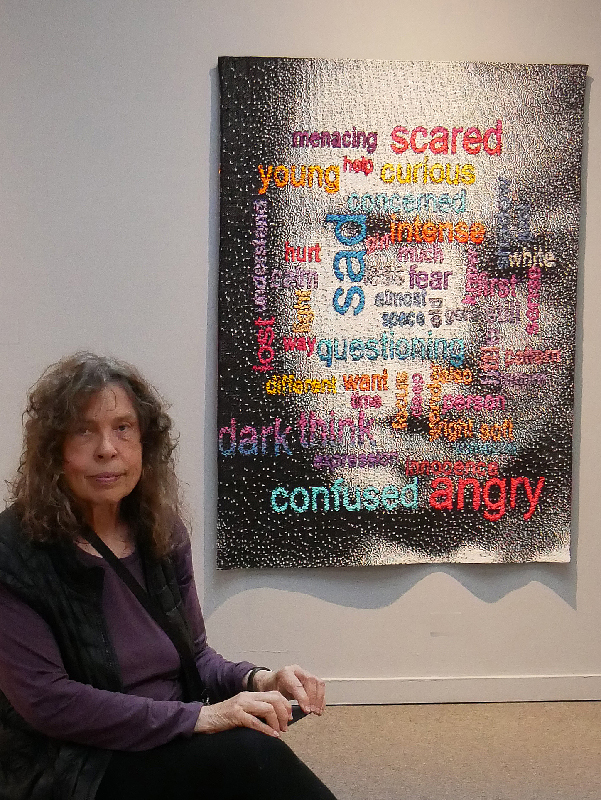

In visual terms, she has found that the neurological lines (neural connections in the brain) made visible through Diffusion Spectrum Imaging (DSI) actually resemble threads or fibres. She went on to integrate a person’s neural connections into their own woven portrait, for instance in Mindmeld, 2016. Her exhibition title, “Inner Traces” refers to these DSI lines in the portraits as well as the emotional response to a woven face. Some works show the results of Lia’s research in the shape of word clouds depicting the feelings experienced by people when viewing a weaving, as seen in “Sad and Curious, 2018”. Others present woven visualised data originally shown to participants during the research project, as in “Positivity Su Data”, 2014.

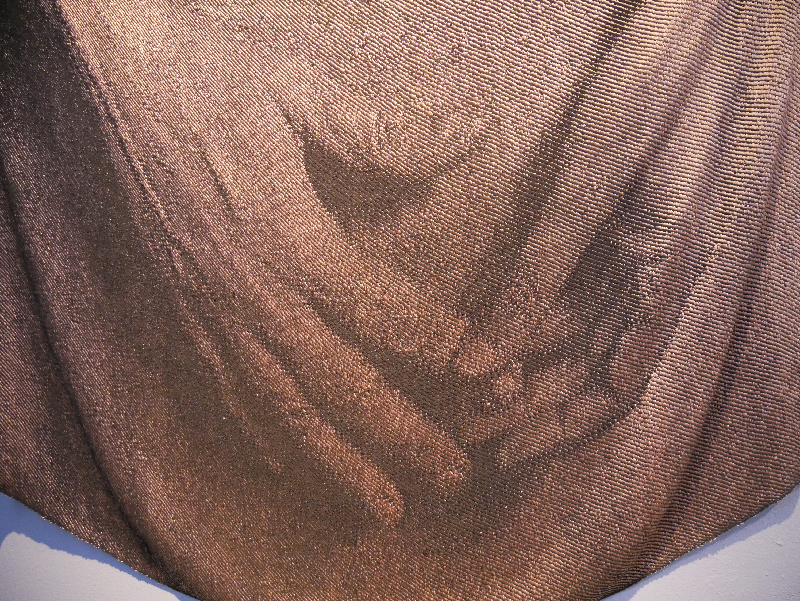

Older works on display included “Presence /Absence Light Touch” dating from 1998 – a woven image of hands on a draped fabric presented on the wall as an actual draped fabric! A three-dimensional piece entitled “Legs” dates back to 1977, a time when the artist worked with foam in order to create three-dimensional tactile qualities. These older works, with their curved lines and illusion of depth, also appear in more recent pieces when the artist uses images of previous works in the background of her portraits, for instance in “Revisioned”, 2018. The optical illusion of these pieces is far more easily achieved now that the computer has entered the world of jacquard weaving.

Lia Cook is an artist who very consistently moved from the complex weaving techniques and weaving experiments she used during the 1980s, including painted, pressed and stuffed warp threads, to jacquard-woven images in the early 1990s, and has became a master of this technique.

When the Lausanne Biennial was discontinued, one of the curators wrote that “the artists were tired”, but this was certainly not true for all artists, at least not for those who worked with digital techniques or new materials like Lia Cook.

Among the journalists who regularly attended the Lausanne Biennials, it was Michel Thomas who envisioned a new age of textile art in the domain of the developing digital age (2). New applications for computer-aided design and manufacture have now entered both industry and artists’ studios.

Lia Cook participated in two early jacquard art & industry workshops, one held in 1981 at the Rhode Island School of Design on a jacquard loom still operated by punched cards, and one held in 1991 at the Müller Zell weaving mill on industrial computerised jacquard looms.

It is remarkable that the commercial art market still strongly focuses on analogue art; I am not aware of any artist working in digital textile techniques who is among the recently (re)discovered and celebrated female artists described in terms such as “overlooked”, “forgotten”, “hidden treasures”, etc. Even in the case of Anni Albers there is now a discussion on why her work should be priced so much lower than that of her husband, Josef Albers.

The next art genre for curators and collectors to discover could very well be jacquard art and other digital art forms. In Europe, a number of jacquard artists I consider some of the best (e.g. LiseFrølund from Denmark) still seem to be unknown in the art market.

Lia Cook is very well known within the art community. Her work sells regularly via two galleries, but no “hype” for it has developed as yet. I am certain that we will see her drawing attention in the not-too-distant future. Her focus on technical perfection, in combination with her subtle themes – first painted folds of fabric and now faces – may not always be well understood. In the days of the Lausanne Biennial during the 1980s, a favourite remark made by artists would be: “My work is not about threads, it is about content”. Lia Cook, on the other hand, always took threads and the ways in which they interlace as seriously as the theme of her weavings.

I had the great pleasure of visiting her in her studio in Berkeley this autumn, an enormous warehouse where she occupies the whole of the ground floor. I saw two antique jacquard looms (one of them in use) next to two digital jacquard looms, TC1s by Digital Weaving Norway, invented by Vibeke Vestby in the early 1990s and now found in many textile departments of universities and artists’ studios. Lia was one of the first to obtain this jacquard sample loom in her capacity as a teacher at the California College of Art and for her own studio.

I was impressed by her meticulousness in keeping actual samples and designs of all her works in her archive, a treasure trove which allows researchers to see exactly what she has achieved in her experiments in creating textiles over the past five decades.

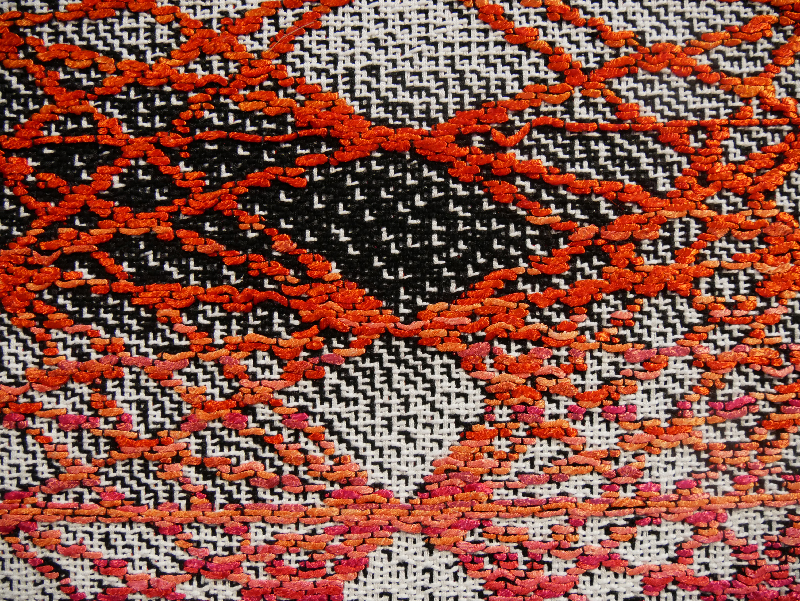

Things are different when you see the studio an artist works in for real, and there were some surprises. In many of her works, she uses a thick irregular rayon yarn which she dyes herself as required (in very shiny bright colours!). When asked if it was still possible to buy this material, she showed me a part of her studio were there were masses of this rayon yarn in white. “I just bought all I thought I would ever need”, she told me!

I was also surprised by her samples. There were some works I had mostly seen in magazines and catalogues, such as those from the 1980s, where they looked pretty flat. Seeing the actual weaving structures added a new material dimension and made the pieces far more interesting.

Viewing parts of Lia Cook’s body of work in real life was an eye opener and a great pleasure.

Beatrijs Sterk

1) In 2010, Lia Cook was invited by Dr Greg Siegle as artist-in-residency for a University of Pittsburg programme, Transdisciplinary Research in Emotion, Neuroscience and Development (TREND), a group within the Department of Psychiatry at the School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh.

2) At the end of the publication, “L´Art Textile”(Edition Skira, 1985, ISBN2-605-00068-0), a chapter entitled “Perspectives” includes a statement by one of the authors, Michel Thomas (page253): “Si la peinture est l´art analogique par excellence, le textile est l´art digitale par excellence et on peut aisement comprendre que la transposition d´un image photographique á trame marquée ou de l´image video composée de multiple points et de multiples lignes est plus facilement réalisable en tapisserie ou en tissage que celle du trait de pinceau.” Translation: “If painting is is the perfect analogue art form, textile is the perfect digital art form and it is easily understood how a photographic image may be transferred by markings on the warp or how a video image made up of many lines and dots is so much easier to realise in tapestry or in dobby weaving than the image of a brush stroke”.