Text by Beatrijs Sterk written for the catalog “Artwork is Cactus” – about the collection of the Museum Angewandte Kunst from 1945 to the Present; Exhibition in Frankfurt am Main from November, 2021

Few concepts are as controversial as textile art, and few art disciplines are so dominated by women. Textile art is the underpaid and unloved sister of fine art. Although increasingly popular among the wider public, those who call themselves textile artists are still battling the negative image of textile art in the art hierarchy. This in spite of the fact that the concept has long been clearly defined: textile art is considered a branch of fine art in those cases where artists focus primarily on expression, which most of them do. Rather than employing oils like painters, they express themselves in coloured threads and fabrics. Could the poor image of textiles be due to this art form being chiefly created by women? This is certainly part of the problem, as is the fact that craftsmanship plays an elementary part in the artistic concept. It is no coincidence that until quite recently the profession was known as ‘artisan’, a term defined by the utilitarian aspect.

Historically, textiles have been associated with the female sex. Even in the modern age, the textile crafts were considered an appropriate pursuit for gentlewomen and a school subject assigned to girls until well into the second half of the twentieth century.

Even at the Bauhaus, an institution that still exemplifies the dawning of the modern age, Walter Gropius considered weaving the suitable sphere of activity for female candidates, whether they wished it or not. It has taken until the present day for Anni Albers, doubtless the most famous representative of Bauhaus textiles, to gain wider recognition. The introduction to her major exhibition held at Tate Modern, London, in 2019 reads as follows: ‘This major retrospective within a museum of modern art will reassess and celebrate the possibilities of textiles, and weaving in particular, as a fine-art medium.’(1) Anni Albers herself voiced the somewhat bitter statement: ‘Galleries and museums didn’t show textiles; that was always considered craft and not art. […] When it’s on paper, it’s art.’(2)

After the closure of the Bauhaus under the National Socialist regime, Josef and Anni Albers were forced to flee to the USA. Their work at the Black Mountain College resulted in a very lively post-war textile scene which became emancipated as early as the 1950s. Many women artists were intent on doing things differently from their male colleagues and thus began to explore the third dimension in their works. With the Lausanne Biennial serving as their platform from 1962 to 1995, they joined forces with great East European textile artists such as Magdalena Abakanowicz from Poland and Jagoda Buić from Croatia to bring about a veritable revolution. This largely happened between 1960 and 1970, a period during which women were successful in asserting their rights. It was the time when modern textile art first gained acceptance as an independent art form. The Lausanne Biennials and the sculptural textile works they featured inspired much interest in textile art, which was echoed in biennials and triennials held in the Netherlands, Scandinavia and Germany.(3)

The cessation of the Lausanne Biennial in the mid-1990s meant the end of a global stage for textile art, but it continued to develop nevertheless. This led to a number of groups being established in Europe, such as the Deutsche Gruppe Textilkunst [German Textile Art Group], which co-organised the Deutsche Biennale der Tapisserie [German Tapestry Biennial] and influenced its change of name to Biennale Textilkunst [Textile Art Biennial].

In East Germany, textile artists who had received an excellent art education were in a much better position – more recognition, more commissions and more textile artists making a living from their work. Moreover, art historians supported them in reappraising the perception of applied art.(4) Following the fall of the Wall, the situation of East German artists started to align more with those in West Germany, which in the case of textile artists was considerably worse.

However, it would take another two decades for public attention to refocus on textile art and for textile media to attract renewed interest. An initial search for textile elements in fine art led to the discovery of women whose work had been underappreciated, resulting in the rediscovery particularly of the older generation of female textile artists.(5)

At the same time, slowly but surely the structures within the large museums changed, and women were now holding positions which allowed them to make decisions. An example of women’s decision-making power coming to the fore was the 2017 Venice Biennial: Christine Macel, chief curator at the Centre Pompidou, had been chosen to curate it. She was only the fourth woman to be awarded this honour, and it is due to her that Venice turned into a textile festival that year. The response to the event in the art press was worth reading, finally putting into words what many had believed for a long time. Comments on the artists read: ‘Given the undeniable quality of these women’s work, why has it been overlooked for so long? Part of the answer – as in many other parts of the labour market and society at large – is simple sexism.’(6) As for the status of textile art: ‘There is no justification for the lower status and lower recognition.’(7)These comments, in the Artsy editorial on 19 June 2017 ‘Why Old Women have Replaced Young Men as the Art World’s Darlings’ recognised primarily older women in the art world.’(8)This preference for older women was due to the mechanisms of the art market, which focused on finding quality works at greatly reduced prices and so discovered the iconic textile artists of the Lausanne period.

What followed were major retrospective exhibitions featuring the ‘grandes dames’ of textile art, including shows on Sheila Hicks in Paris in 2018, Anni Albers in Dusseldorf in 2018 and London in 2018/19, Olga de Amaral in Brussels in 2018 and two exhibitions on Magdalena Abakanowicz in Lodz, Poland, in 2018. Finally, Hannah Ryggen was featured at documenta in Kassel in 2017, and her work was showcased in an additional exhibition held in Frankfurt in 2019 (9).

The artists still alive among those mentioned above are Sheila Hicks and Olga de Amaral, and both are now quite advanced in age. The exhibitions not only reflect a re-evaluation of women as artists but also a reappraisal of textile art in the context of fine art.

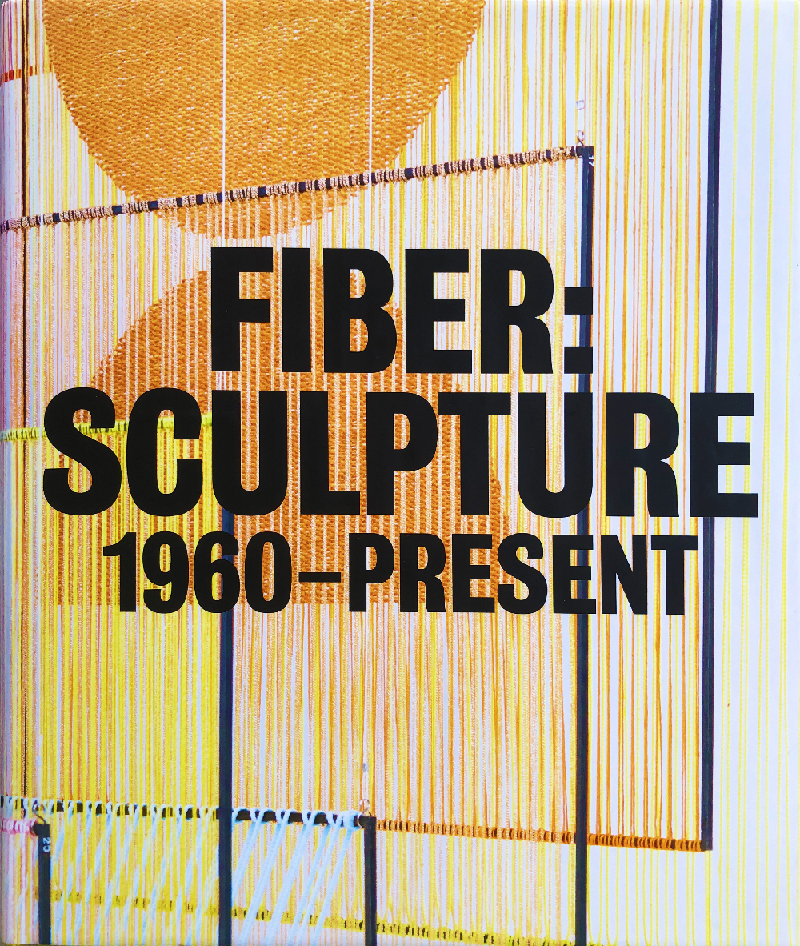

This rediscovery of textiles as part of the fine arts could be perceived in the USA from around 2009.(10) On the European continent, this revived interest manifested itself in 2014. Initially it was seen as merely a temporary phenomenon in art, but gradually it became established. In the USA, curator Jenelle Porters set herself clear goals when organising the 2014 exhibition Fiber: Sculpture 1960–Present at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston: ‘This is the first exhibition in 40 years to examine the development of abstraction and dimensionality in fibre art from the mid-twentieth century through to the present.’(11)

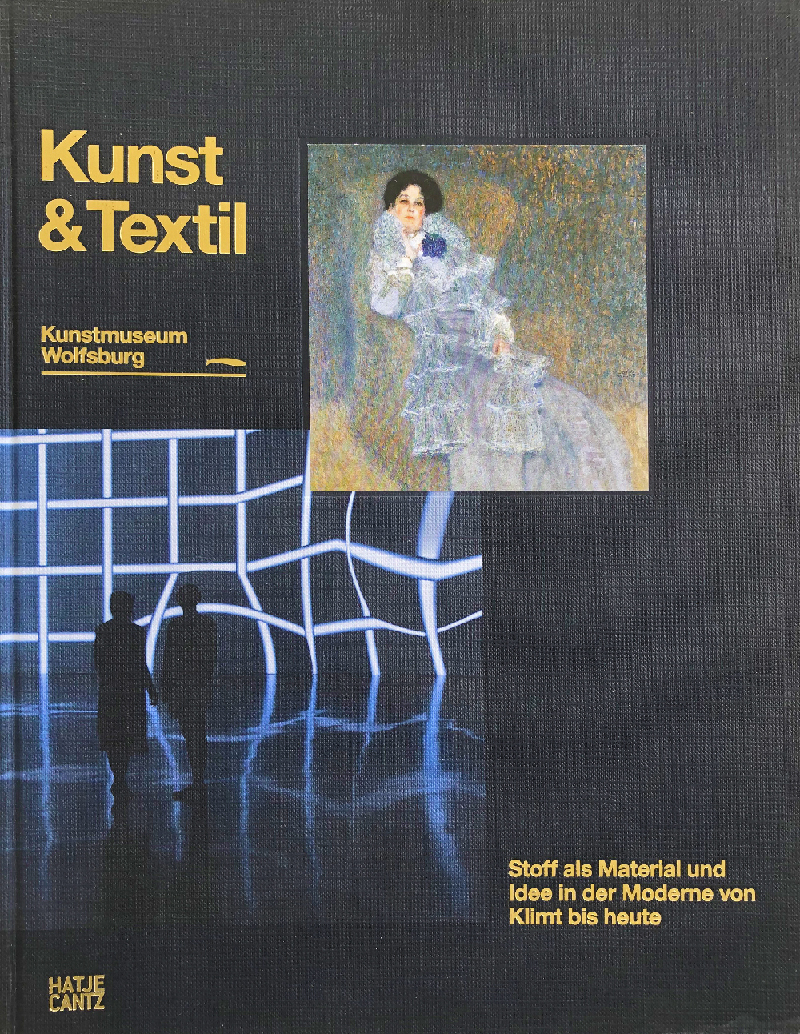

The first significant exhibition in this field to be held on the European continent was Art & Textiles, presented in Wolfsburg in 2014 and subtitled Fabric as Material and Concept in Modern Art from Klimt to the Present. Markus Brüderlin, director of Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, and his team worked on the accompanying catalogue for over three years in order to highlight every aspect of art and textiles. At the press conference that marked the opening of the exhibition, it was stated that Angela Volker, curator of textiles at the Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, had been called in as an expert. Further enquiries revealed that she had merely been asked to edit the captions and had not been consulted on the textile content. Her name is not listed in the imprint.

Great ideas were obviously in the air and seemed to mature all of a sudden, because that same year there were a number of further ‘art and textiles’ exhibitions, such as To Open Eyes: Art and Textiles from the Bauhaus to Today in Bielefeld. France had hosted Decorum. Artists’ Carpets and Tapestries at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 2013/14, and in Italy Soft Pictures was held in Turin in 2013/14. In London, an exhibition entitled Artists’ Textiles: Picasso to Warhol took place at the Fashion and Textile Museum in 2014, and in the Netherlands, Threads: Art as a Metaphor for Interweaving was held at Museum Arnhem, likewise in 2014.

When asked about their motivation for presenting textiles, the curators of art museums consistently replied that the world of computers offered so much in the way of virtual reality that people had become hungry for tangible and sensory experiences.(12)

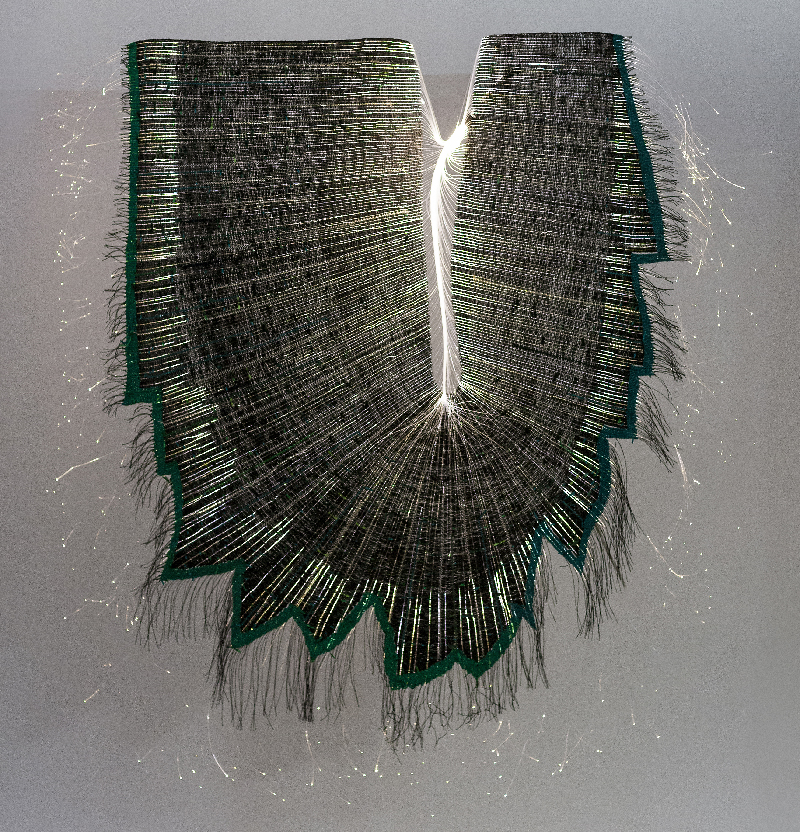

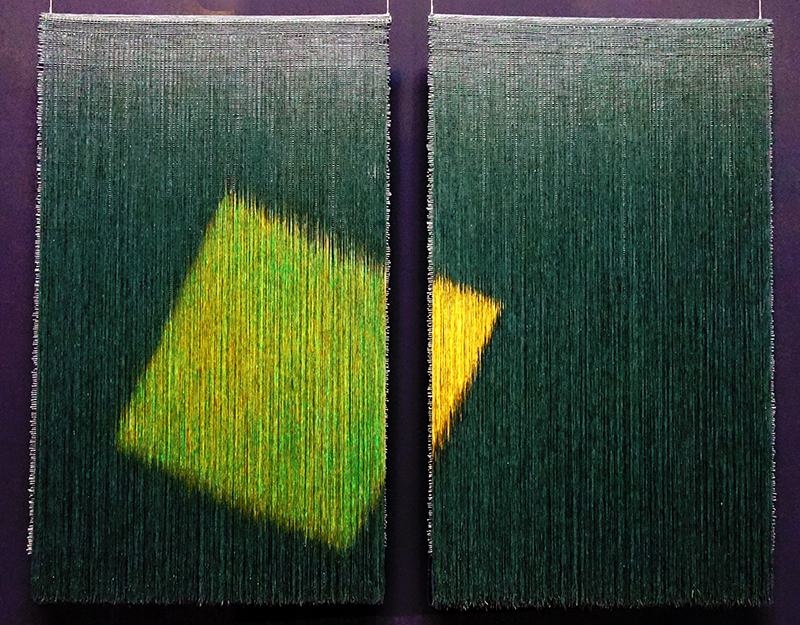

The same premise was put forward in Vitamin T, Threads and Textiles in Contemporary Art, a publication in which over 100 curators of fine art were asked to name artists who use textiles and threads in remarkable or innovative ways.(13) Only four of the 113 artists thus selected came from the field of textile art, and all four of them were female and older. Although textile techniques are being highlighted again as means of expression, they still meet with a lack of knowledge and ignorance on the part of the younger generation of textile artists. When it comes to innovative approaches to textiles, one of the many names that come to my mind is Włodzimierz Cygan, a Polish artist who has managed to create a range of completely new means of expression in weaving, sometimes employing new materials such as light-conducting fibres.

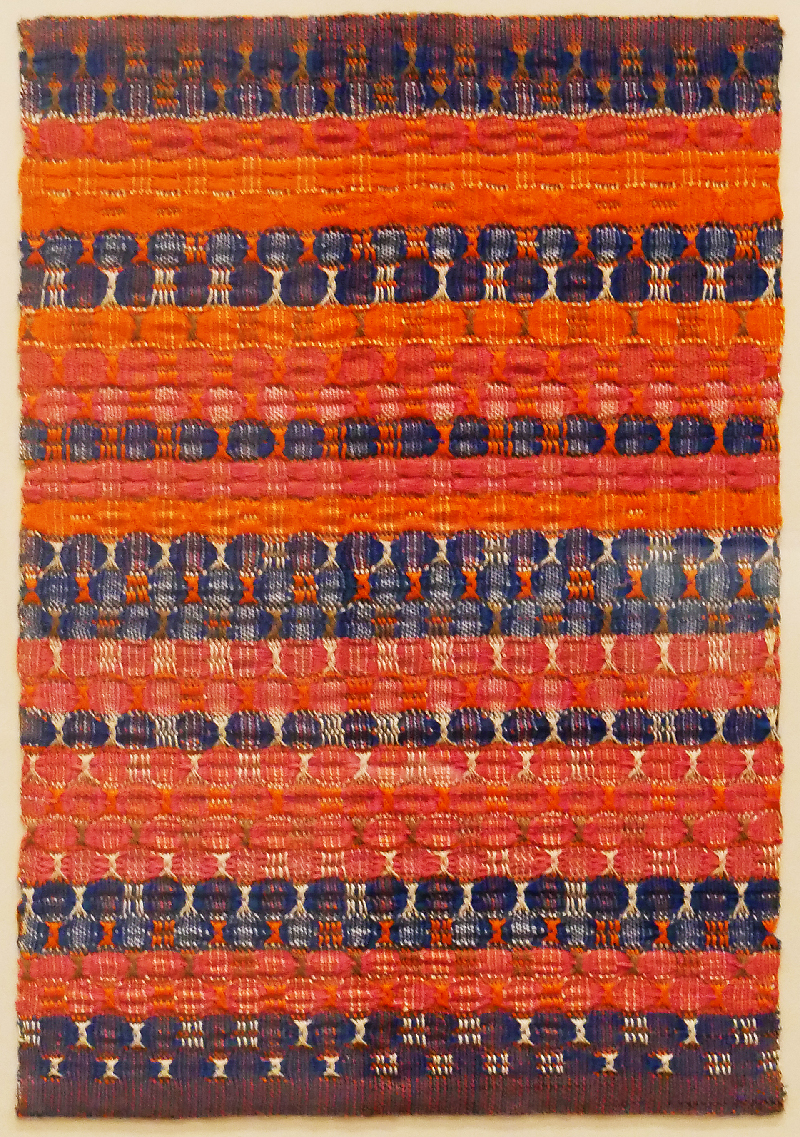

Let us take the Bauhaus weaving department as the starting point for examining the ancient technique of weaving. Bauhaus and its drive to produce applied art for the masses has led to machines and computers blurring the boundaries between crafts, design and art. Of particular note is the computer-aided TC1 jacquard handloom invented by the Norwegian weaver Vibeke Vestby in 1990, which allows completely free compositions in handweaving.(14) This option for weaving highly complex patterns is largely employed by textile training centres as well as fine artists. For instance, there is now a trend for painters to have their works reproduced on industrial weaving machines.(15)

However, there are also some very interesting examples where textile artists have been skilful and artistic in engaging with the technique of jacquard weaving. In the USA, Lia Cook is the most renowned artist in this field. In Europe, the artists most noted for jacquard work in textile art include Grethe Sørensen and Lise Frølund from Denmark as well as Philippa Brock from the UK.(16) Notable names in the field of design include Hella Jongerius from the Netherlands.

The ancient technique of tapestry weaving, which has been thriving again across the globe since the late 1980s, acquired a contemporary exhibition format in Europe in 2001: the European Tapestry Forum (ETF) based in Denmark is the organiser of the Artapestry triennial.(17) The sixth exhibition was launched in the Danish town of Silkeborg in January 2021.

Embroidery, too, has seen a global revival and is becoming internationally more significant. Outstanding examples are presented at the Rijswijk Textile Biennials near The Hague.(18) Curated by Anne Kloosterboer, they have given centre stage to textile art and its ingenuity, and hand embroidery has increasingly displayed a stunning wealth of variety. This highly personal and very slow diary-like work is creating a new kind of intimacy. Young people in particular seem to go in for this intense form of expression.

A major patchwork and quilt movement has taken primarily in the USA. There are various patchwork/quilt groups and exhibitions in Europe, and some of them target textile artists. The most important event is the European Quilt Triennial that has been presented at the Max Berk Textile Museum, Heidelberg, since 1986.(19) Other techniques such as felting or use of felt; knitting, crochet and free applications of these; appliqué and collage techniques using textile materials; bobbin and needle lacemaking or machine embroidery; and dyeing techniques and their interpretation in two-dimensional and three-dimensional space are currently not presented in dedicated exhibition formats but are still part of textile art. Ever since Lausanne, various disciplines of textile art have had their limelight moments which were often triggered by major shows or exhibition series. The time has come to rewrite the history of contemporary European textile art in the post-Lausanne period in order to do justice to every movement in textile art, and to counter the ignorance mentioned earlier.

The collection of the Museum Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt am Main does not presume to adequately represent all these developments in textile art. However, as a museum of applied art, formerly of arts and crafts, it addresses the artistic relevance and cultural role of textile art in the context of its collections. In many disciplines of textile art, we encounter works by female and, more rarely, male artists which represent distinctive aspects of this field. They highlight forms of artistic expression that support the case for their inclusion in fine art, and rather than offering mere retrospectives, they can be considered inspirational or predictive.

The interest being shown by the younger generation in textiles as an artistic form of expression is based on a great number of very different reasons. Not only will they place increasing importance on sustainability in the sense of a no-waste approach, but there is also a growing curiosity about textile materials and textile techniques. This curiosity appears to be two-fold. On the one hand, there is an interest in new materials and techniques such as optical fibres, electronically conductive textiles, textiles reactive to sound and chemicals, 3D printing for textile structures, laser cutting and computer-aided jacquard weaving. On the other hand, there is a return to archaic procedures – ‘slow textiles’ as an analogy to ‘slow food’. Natural materials and old craft techniques are celebrating a comeback on account of a new awareness of social responsibility. In October 2020, this was illustrated by the Textile for Future conference, a discussion forum on the prospects of textile design/textile art involving lecturers and professors from Scandinavia, the Baltic countries, Poland and the UK.(20)

Lidewij Edelkoort, probably the most renowned futurologist who has believed for some time that crafts will become essential for our future, joined forces with Philip Fimmano to write A Labour of Love.(21) It is a celebration of crafts, including textile crafts. A remarkable fact is that the usual categories of applied art, fine art and design no longer seem to play a role. The bottom line for textile art is that never before has it attracted this level of public interest. The greatly increased demand for weaving at Scandinavian universities is a case in point. However, opinion leaders in fine art are struggling to give textile artists the credit they deserve, especially the younger generation. As shown by the examples cited above – Markus Bruderlin not even consulting a textile curator, and the lop-sided selection presented in the Vitamin T publication – textile art still has a long way to go to gain equal status.

1 Ann Coxon, curator, Tate Modern.source:Tate Modern, an Anni Albers Retrospective” von Farah Nayeri, 8 Oct.2018; Website: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/08/arts/tate-modern-anni-albers-retrospective.html

2 Anni Albers, 1984. Source:1. Internet article in Wallpaper “The Anni Albers retrospective at Tate Modern anticipates 100 years of Bauhaus” by Harriet Lloyd-Smith; website: https://www.wallpaper.com/art/anni-albers-retrospective-tate-modern-bauhaus-100-years

3 In the Netherlands, there were three editions of the Werke in Textiel Triennial at the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem (1968, 1971 and 1974). In Germany, the Deutsche Biennale der Tapisserie was held six times at different venues between 1978 and 1990. In Scandinavia, the Nordic Textile Triennial was shown seven times as a travelling exhibition touring the Nordic countries between 1974 and 1995. A biennial has been held in Lodz, Poland, since 1972; later it was changed to a triennial that still takes place today with international participants.

4 Rainer Behrends, ‘Über das Verhältnis von Kunsthandwerk und Realität’ [The Relationship between Applied Art and Reality], Textilforum 2/1987, p. 34.

5 For instance, Victoria Pomery, director of the Turner Contemporary in Margate, UK, noted that a search for ‘works by unknown artists who employ textiles’ resulted in female names only. This made women a search criterion. ‘Women very actively engage in the use of materials, in particular textiles and threads’, says Pomery in the catalogue Entangled: Threads and Making (Margate, 2017).

6 Anna Louie Sussman, 2017, ‘Why Old Women Have Replaced Young Men as the Art Worlds Darlings’, Artsy, 19 June 2017, accessed 25 August 2021, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-women-replaced-young-men-art-worlds-darlings

7 Statement by the art dealer Fergus McCaffrey, New York, in ibid.

8 See ibid.

9 Sheila Hicks, Lignes de vie / Lifelines, 2018, at the Centre Pompidou, Paris; Anni Albers: Retrospectives in Dusseldorf in 2018 and at the Tate Modern, London, in 2018/19; Olga de Amaral Light of Spirit, a 2018 retrospective at La Patinoire Royale – Galerie Valérie Bach, Brussels; Magdalena Abakanowicz, Metamorphism I and II, 2018, at the Textile Museum of Lodz, Poland; and Hannah Ryggen at the 2017 Kassel documenta and Hannah Ryggen: Gewebte Manifeste at the Schirn-Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, in 2019.

10 ‘The point at which fiber reached critical mass, quite literally, was in 2009 when Franco Sofiantino Contemporary Art Productions from Turin, Italy, exhibited Michael Butler’s two-ton rag rug in a small booth at the Art Basel Miami Beach.’ Joanne Mattera, former editor in chief of Fiberart magazine, ‘Fiber, Fiber Everywhere’, Surface Design Journal, Fall 2013.

11 Fiber: Sculpture 1960 – Present; editor Jenelle Porter; Prestel Verlag, 2014

12 Markus Brüderlin writes in his introduction to the Kunst & Textil – Stoff als Material und Idee in der Moderne von Klimt bis heute, edit. Markus Brüderlin, Hatje Cantz Verlag 2014, p 10: ‘It is the growing virtualization of our world by computers and the internet that has given crafts this new topicality. […] There is no substance, no material and no technology that has the power to touch both our sensory and mental existence as universally as textiles, and this is happening in a period that is in danger of becoming more and more non-sensory and intangible.’Translated from the German text by Suzanne Mattern.

13 Vitamin T: Threads and Textiles in Contemporary Art (London, 2018), published by Phaidon Press, 303 pages, 391 photos.

14 Vibeke Vestby, then a lecturer at the Art and Design College in Oslo, received funding from the IT programme of the Norwegian Ministry of Education in 1990, with emphasis on traditional crafts and women.

15 For example at the Textielmuseum, Tilburg, Netherlands, but also in a factory in Wielsbeeke, Belgium, which weaves small series that are sold as so-called multiples, similar to graphic art, on the art market.

16 Such as Outi Martikainen from Finland, Francesca Piñol from Spain, Monika Grašienė-Žaltė from Lithuania and Krista Leesi from Estonia.

17 A tapestry exhibition of works woven by artists, organised by the ETF association and shown at various European locations.

18 There have been six exhibitions to date. A seventh edition is planned for June 2021.

19 The next European Patchwork Triennial is scheduled there in 2021 as the 8th European Quilt Triennial.

20 ‘Vilniaus dailės akademijos Kauno fakultetas’, 2020, International Conference: Textile for Future, Facebook, 22 October 2020, accessed 2 September 2021, https://www.facebook.com/1488489964737074/videos/721890645086551; https://www.facebook.com/1488489964737074/videos/340287487261508; https://www.facebook.com/1488489964737074/videos/690460465010027; and https://www.facebook.com/1488489964737074/videos/399916821402795

21 Edelkoort, Lidewij and Filip Fimmano, eds., A Labour of Love (Eindhoven, 2020), 446 pages, 290 colour photos; catalogue for the exhibition La Manufacture: A Labour of Love, September–November 2020 in Lille, France.