Else Mögelin – Bauhaus and spirituality in Pomerania

Exhibition from April 11 to June 9, 2024 in the National Museum in Szczecin

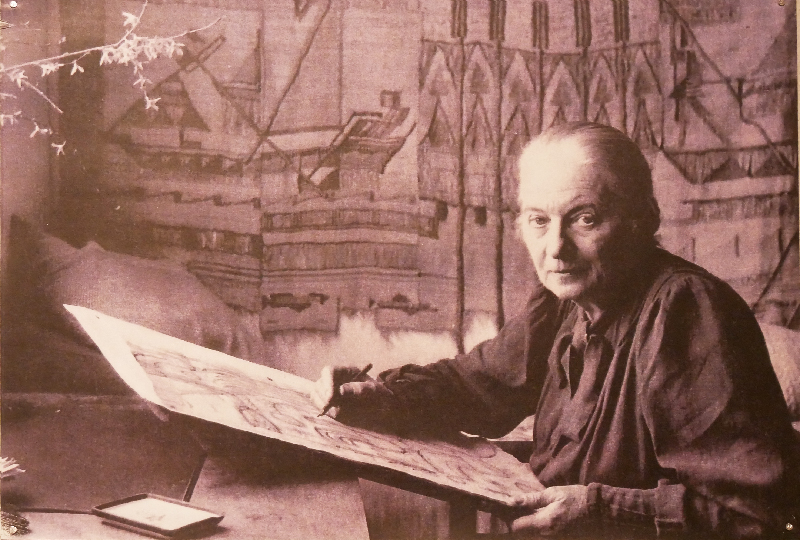

I found out about this show on Bauhaus weaver Else Mögelin through friends at the Szczecin Art Academy, and because I had met this weaver in person at the end of the 70s, I really wanted to see the exhibition. I wasn’t disappointed, because the show in the National Museum of Szczecin was the best I had recently seen! This was also because the curator, dr Szymon Piotr Kubiak, had put a lot of effort into the presentation of the exhibition. It seemed to me that he wanted to recreate the Bauhaus avant-garde using today’s means, which resulted in a timeless exhibition design. The large Anni Albers exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf was similar in the “Bauhaus style”, resembling an early exhibition from 1949 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

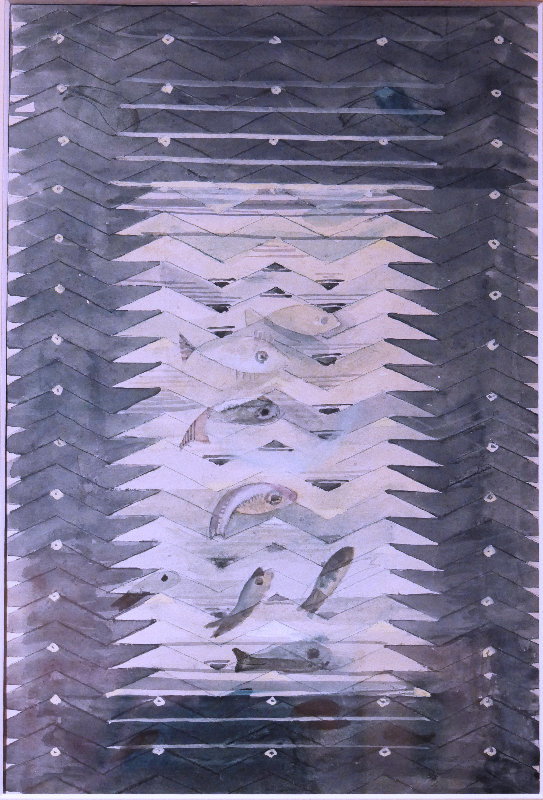

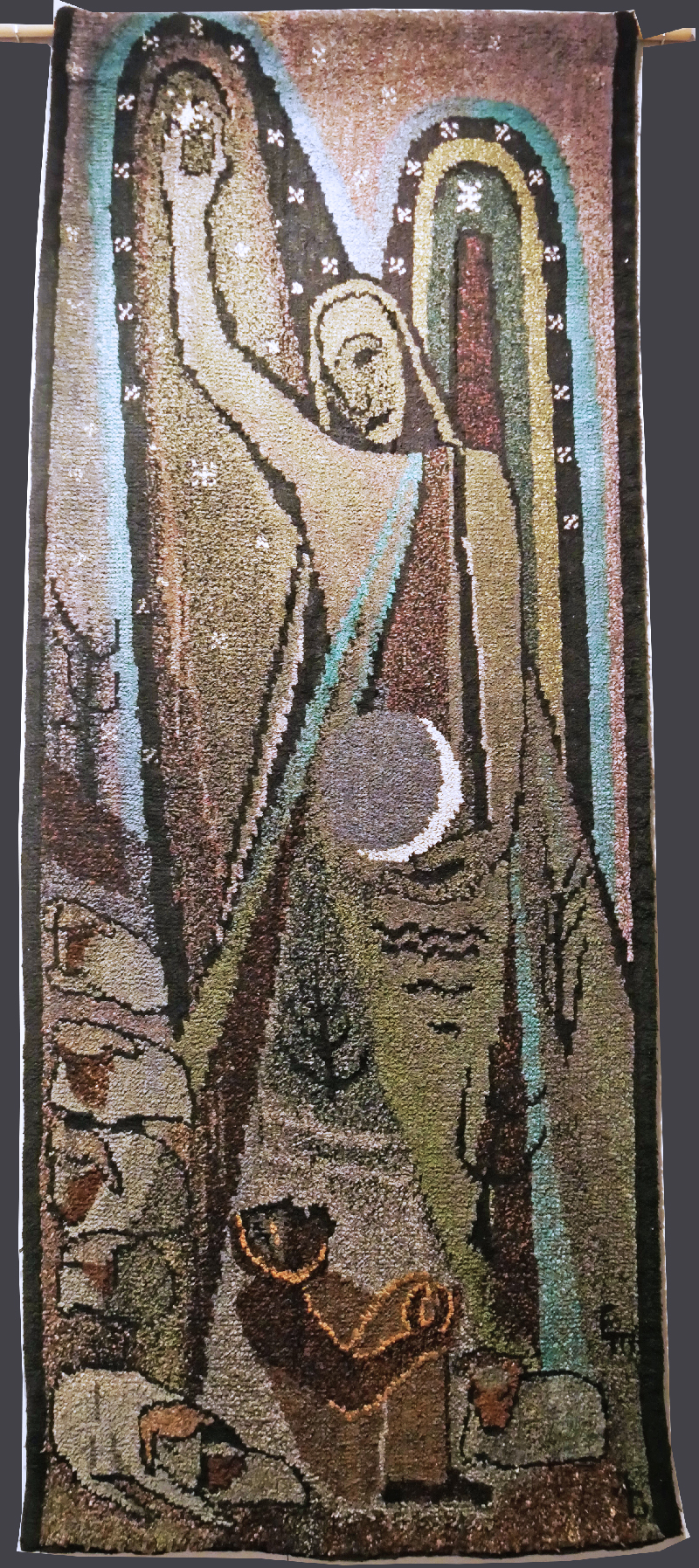

The labeling in the Szczecin exhibition was also exemplary in German and Polish and helped to understand the topic of “Bauhaus and spirituality”. This meant the concept of the sacralization of nature and landscape painting as a work of modern religious art. According to the explanation on the plaques, the origin of this movement, in what was then the German province of Pomerania, had its origins in the romantic works of Casper David Friedrich and Otto Runge. This was new to me because I had associated the spirituality of the Bauhaus with esotericism; the Mazdaznan teachings, the anthroposophy and theosophy of Johannes Itten, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Georg Muche and others. In relation to Else Mögelin, nature as an emanation of the divine was already present in the works from the time of the First World War and always remained recognizable as a theme of her work also after 1945.

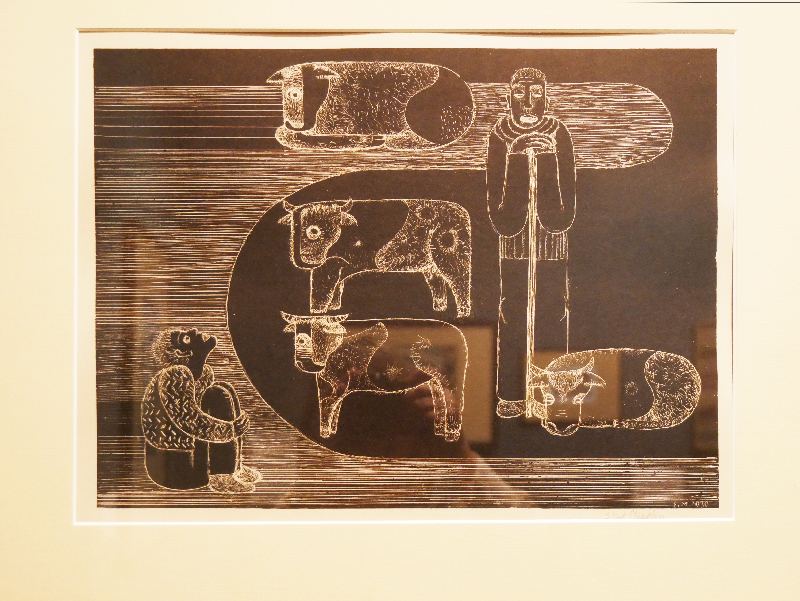

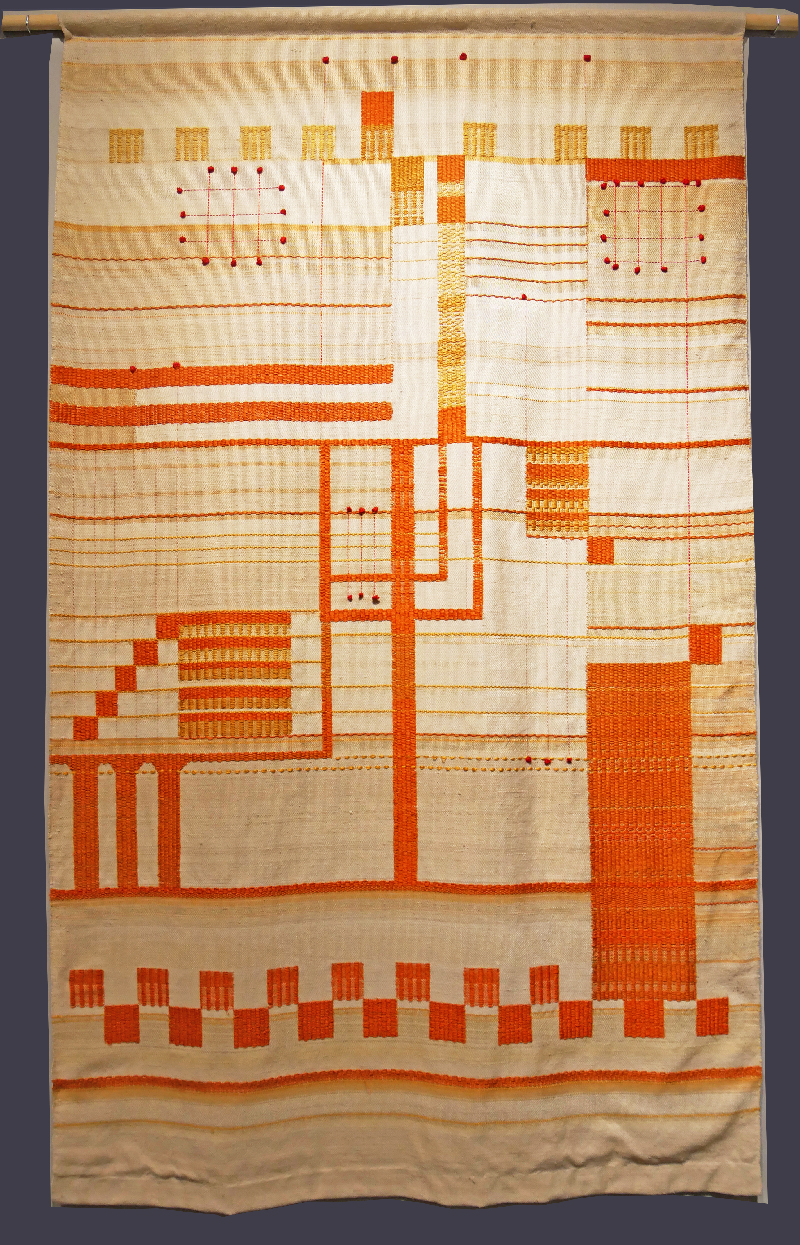

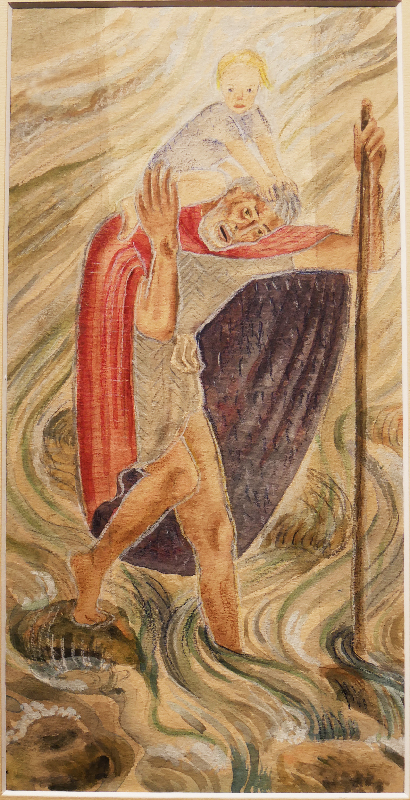

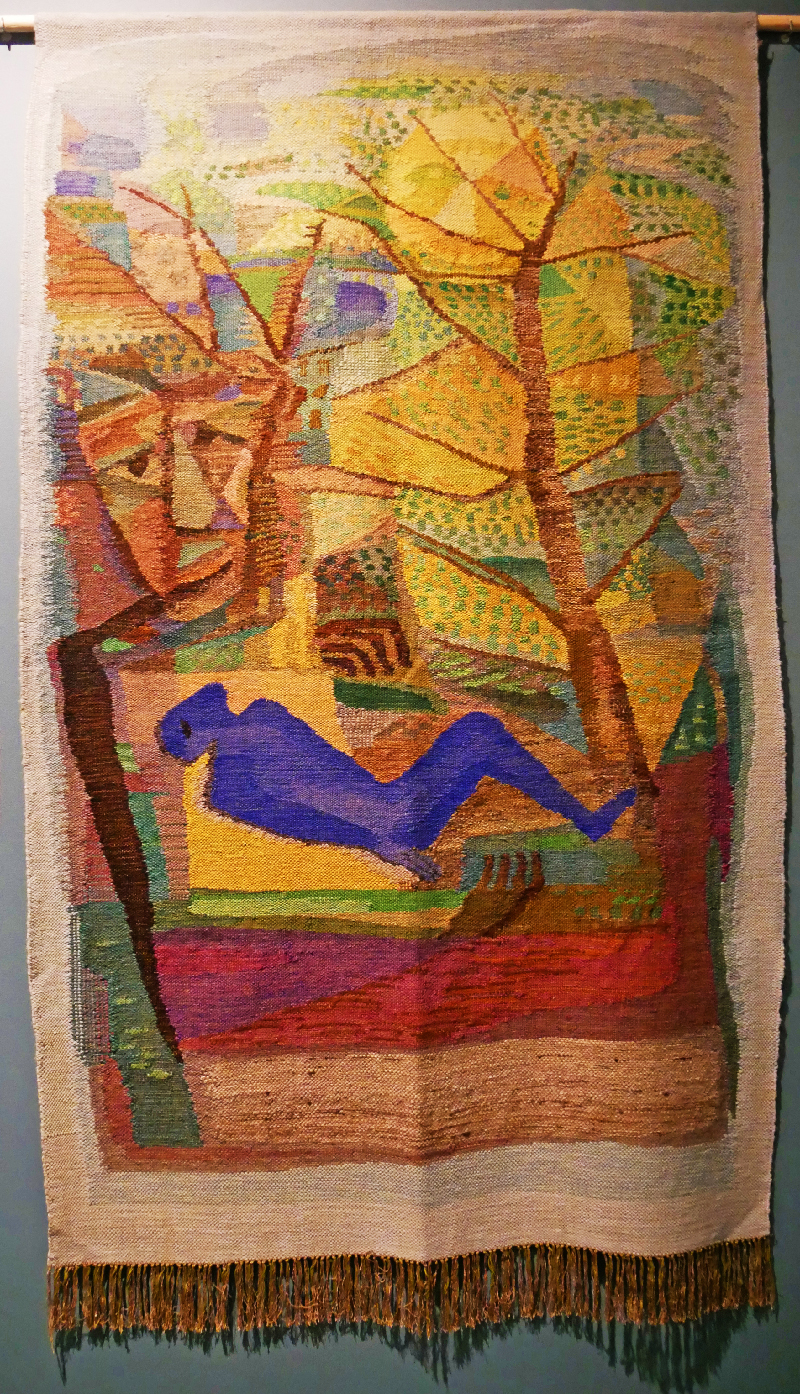

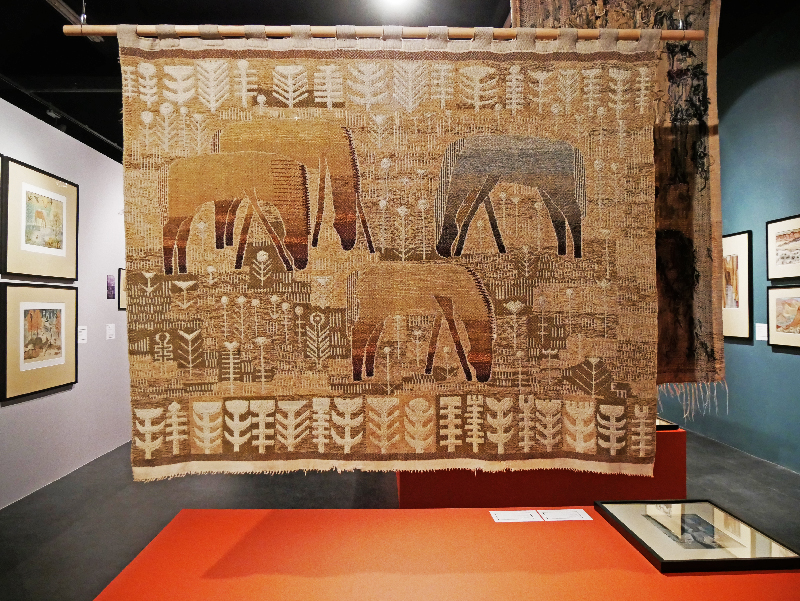

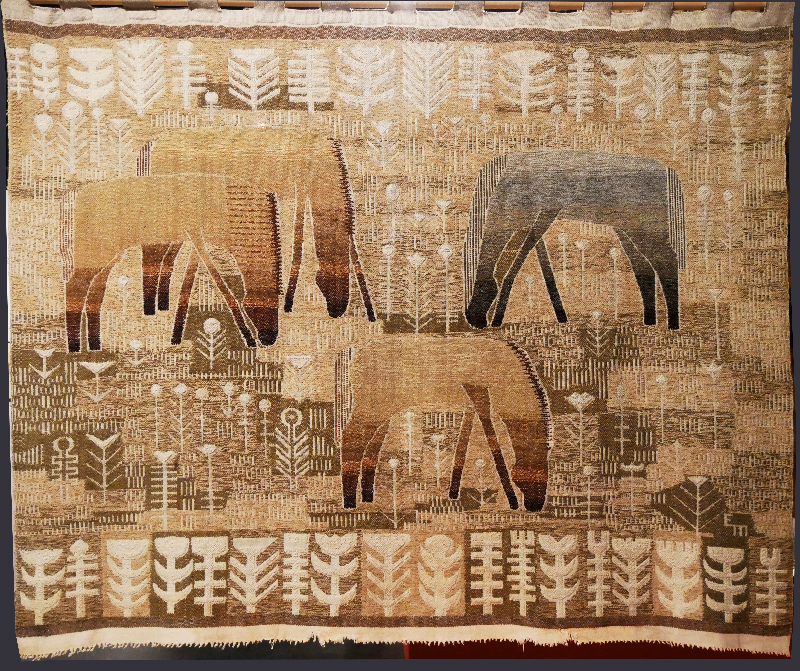

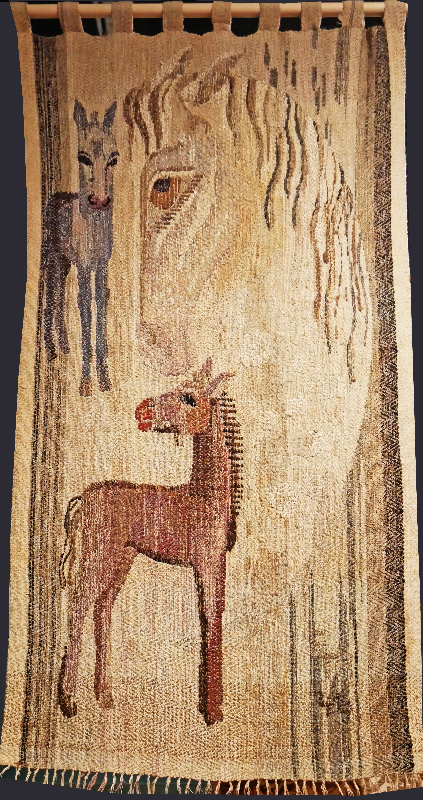

The Szczecin exhibition mainly featured graphic art, designs, watercolors and tapestries by Else Mögelin. These were woven in different weave structures and materials on a multi-shaft loom with a visible warp, a similar technique as used by Johanna Schütz-Wolff (also called „halve-gobelin“). It further seems that Mögelin also had woven from her watercolors without using a precise cartoon. Other weavers had and have also used this way of tapestry weaving directly from a small design. It would be interesting to find out whether this creative approach originated at the Bauhaus, as I think it did.

As a graduate of the Bauhaus, Mögelin brought innovative design and didactic methods to what was then the German province of Pomerania. From 1927 – 1942 she headed the textile workshop at the Municipal Crafts and Applied Arts School in Szczecin, which cooperated closely with the Municipal Museum under the direction of Walter Riezler. The achievements of lecturers and students were always presented, thereby promoting modern trends in art. From the circle of artists around Else Mögelin were works by Friedrich Bernhardt, painting; Otto Lindig, ceramics; Kurt Schwerdtfeger, also a Bauhaus graduate and head of the school’s sculpture studio, shown in the exhibition. The school’s director was the architect Gregor Rosenbauer, also a supporter of modern art. In 1930, Friedrich Bernhardt founded the “New Pomerania” group with the support of Walter Riezler. The connection between art and life, which was important for the Bauhaus, survived the Nazi period, but Rosenbauer and Riezler quickly lost their positions.

Another focus was the increased interest in modern Protestant art. In 1929, drawings, models and photographs of modernist Protestant churches were shown in the Municipal Museum. Lecturers from the Szczecin school took part and Mögelin also received orders from the Pomeranian Protestant communities.

One of the first weavings in the exhibition was a wall hanging based on the well-known photo of Walter Gropius’ study, designed in 1923 by Else Mögelin, recreated in 2018 by Anna Silberschmidt from Studio Aphorisma in Tuscany. I found this work particularly successful and can imagine how much empathy and imagination played a role here. Else Mögelin saw her time in Szczecin, especially the early 1930s, as her best time. It is a pity that very few works from that time were on display, as many works seem to have been lost in the fire at the Szczecin school’s weaving workshop in wartime.

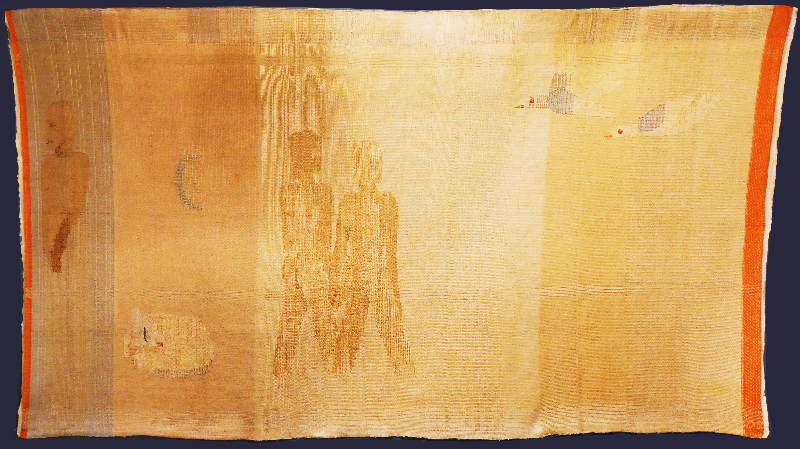

While wandering through the exhibition with some 15 wall hangings, many watercolors, prints, jacquard fabrics, carpet designs, pottery, religious designs and photos of works in churches, the Leipzig exhibition from 2015 with Johanna Schütz-Wolff came to my mind. Just as talented as Else Mögelin, Schütz-Wolff never achieved the fame of Anni Albers. At that time I wrote that it was probably because nothing that came from the GDR was noticed in West Germany! But that was not true as she was living and working in West Germany since 1940! What about Else Mögelin who in 1945 became a lecturer for textiles at the Hamburg Art school? She represented Germany at the Milan Triennale in 1951 with the wall hanging “The Earth” and in 1953 she was represented with three wall hangings at the exhibition “Woman as Creator”. In 1961, in collaboration with Maria Thierfeldt, also a Bauhaus graduate, the wall hanging “People” was created for the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany in Stockholm. After her retirement, she also had many commissions from churches, including designing the “Bugenhagen carpet” for the so-called “Pomeranian Chapel” (1955 – 1962) at the Nikolaikirche in Kiel, which was carried out by her master student Brigitte Schirren. But like Johanna Schütz-Wolff she didn’t achieve anywhere near the level of fame of Anni Albers or Gunta Stölzl. Luckily there is a renewed interest in this Bauhaus weaver; the exhibition “Else Mögelin – I wanted to weave – against all obstacles” took place from 2.12.23 to 3.3. 2024 in the Brandenburg State Museum for Modern Art in Germany, as well as now the even more extensive show in Szczecin, Poland, an exhibition that deserves to be seen in several places.

The question arises as to how Else Mögelin survived the Nazi era when Johanna Schütz-Wolff had cut up her own work because it was considered „degenerate“ and no longer received any allocations of material during wartime (as I learned in a conversation with weaver Allen Müller-Hellwig ). Although some of Mögelin’s work was removed from public collections as “degenerate”, her work benefited from the fact that the Nazi regime was fond of craft. Mögelin had made a name for herself with the weaving workshop of the Gildenhall artists’ community, where she took over the textile workshop in 1923 and with which she continued to be associated as a consultant from 1927, and received many orders as a result. She was not, like Alen Müller Hellwig and Irma Goecke, the first choice for representative buildings of the Nazi regime, but followed a consciously cautious course. She wrote: “If an artist wanted to work back then, he/she had to make concessions – the problem was to maintain the right level that was still acceptable to the artistic conscience.” She was also not married and had been living with the weaver Jeanette Ganzert since the 1930s, which was not norm at the time. Her strong Christian influence and her connection to the Bauhaus and representatives of modernism were also not welcomed. During this time, Else Mögelin repeatedly escaped into nature and her artistic work. This inense connection to nature and its symbolism (e.g. runes) had shaped her style for many years and was repeatedly expressed in her work. The difficult procurement of orders during the Nazi era, indirectly through the former directors, also shows the problems in the system at that time.

A lot of background knowledge was given to me by Kathrin Daßler & her partner, the gallery and art dealer “Blaue Brücke” in Dresden, collectors of Else Mögelin’s works. Both of them were present at the opening and I owe it to them and to dr Dariusz Kacprzak, vice-director of the State Museum, that I was able to see Else Mögelin’s former home and learned a lot about the changes in Szczecin after 1945 on a small city tour.

On occasion of the opening, a workshop was held to accompany the exhibition, organized by the Warsaw Bauhaus Foundation, an initiative by Joanna Klass and Wojtek S., which was founded to save an early building from 1906 by Walter Gropius and to carry out social-cultural projects there. This workshop reminded me of my Dutch creativity training from the late 60s!

Overall, the trip to Szczecin was very positive and I was happy and grateful that I was able to be there at the opening! In my next post I hope to show the catalogue of this very beautiful exhibition, which will be published in some weeks.