Es gibt kaum einen schillernderen Begriff als den der TEXTILKUNST!

Wir Kinder der Nachkriegszeit sind mit den Lausanne-Biennalen aufgewachsen, die wir als Textilkunstveranstaltungen wahrgenommen hatten. Es waren spannende Präsentationen textiler Provenienz, die sich auf der Bühne einer Tapisseriever-anstaltung abgespielt hatten. Das war in einer Zeit, in der das Kunstverständnis in Frage gestellt wurde und sich die Frauenemanzipation beschleunigte.

Dennoch erwies sich das Wort Textilkunst selbst als brüchig. Für konservative Geister lag die Betonung auf ‘Kunst’, während die ins Rampenlicht tretenden Frauen ihre textilen Beschäftigungen zu professionalisieren begannen.

Im zweiten Jahr der Existenz unserer Zeitschrift sahen wir uns zu der Feststellung genötigt, dass Textil kein Stoff sei (TF 2/1983, S. 1). Denn in der Tat ist Textil weder ein Material noch eine Technik, sondern eine Weise des Herstellens mittels biegeschlaffer Materialien und eigener Techniken, vergleichbar der Architektur, deren Resultate auch aus (vergleichbar festem) Material mittels bestimmter Techniken hergestellt werden, ohne selbst Material oder Technik genannt zu werden. Diese Besonderheiten sind es, Textil und Architektur nicht einem Selbstzweck zuzuordnen, den man mit ‘Kunst’ verbinden kann. Denn diese Disziplinen sind immer funktional; sie repräsentieren auf unauflösliche Weise immer Körper und Geist.

Wer Textil als ein Material versteht und entsprechend benutzt, entfremdet es seines Sinnzusammenhangs und erstellt bestenfalls ein Kunstwerk. Dann allerdings ist das Textile an der Kunst unwesentlich und der Name Textilkunst irreführend.

DIE VORGESCHICHTE HEUTIGER TEXTILKUNST

Man kann vermutlich davon ausgehen, dass sich das Textile parallel zur menschlichen Sprache entwickelt hat. Text und Textil sind ihrer Herkunft nach sprachverwandte Begriffe. Die Kulturwissenschaften betrachten die textilen Künste quer zur jeweiligen Nutzanwendung als Zivilisationsleistungen, nur dass sie sich anders als beispielsweise Keramik und Gebäude über die Zeiten weniger erhalten haben.

In jüngerer Zeit und unter heutigem Kunstverständnis sind Textilien während der Arts & Crafts-Bewegung und in der Zeit des Jugendstils als Bestandteile des Gesamtkunstwerks, der Einheit von Architektur und Inneneinrichtung, ins Blickfeld geraten. Auch während der russischen Revolution gab es die Tendenz zur Rückkehr der Kunst in den alltäglichen Gebrauch. Nach dem 1. Weltkrieg propagierte das Bauhausmanifest: „Architekten, Bildhauer, Maler, wir alle müssen zum Handwerk zurück! Denn es gibt keine Kunst von Beruf.“ Die Funktionalität von Textilien wurde im Bauhaus neu hinterfragt und die Jacquardtechnik wieder für die Vervielfältigung bildkünstlerischer Darstellungen verwandt. In der Gestaltung war ein Klima der Offenheit und Experimentierfreude entstanden, das nach dem Exodus der Bauhäusler aus Nazi-Deutschland (überwiegend in die USA) im Ausland auf fruchtbaren Boden fiel.

DIE EXPLOSIONSARTIGE NACHKRIEGSENTWICKLUNG

Wir sehen die Anfänge in den USA. Beim Nachlesen der Texte z. B. von Claire Zeisler (1903-1991)1), bedeutete für sie die Arbeit in Textil eine neue Freiheit, die sich am bestehenden Kunstestablishment vorbei auf die altperuanische Weberei bezog.

Die erste Arbeit mit komplett sichtbarer Kette hieß „Space Hanging“ und war 1953 bei Lyn Alexander entstanden. Lenore Tawney (1907-2007), die neben Claire Zeisler, der noch lebenden Sheila Hicks (*1934) und anderen 1964 im Zürcher Museum für Angewandte Kunst unter dem Titel „Woven Forms“ erstmals in Europa ausgestellt hatte, war 1954 von der Bildhauerei zum Weben gewechselt. Sie fand übrigens erst 1975 Eingang in die 7. Lausanne-Biennale und stellte 1983 auf der 11. Biennale ein letztes Mal aus: eine Arbeit mit von der Decke hängenden Fäden, genannt „Cloud Labyrith“.

Die Weberin und Buchautorin Ruth Kaufmann bemerkt in ihrem Buch „The New American Tapestry“ aus dem Jahre 1968 2), dass in jener Zeit eine Lust am Abenteuer vorherrschte. Mit Blick aufs Bauhauserbe schrieb sie: „Das Bauhaus vereinte den Geist des Experimentierens mit dem freien Spiel und einem sorgfältigen Studium der Eigenschaften des Mediums“. Bemerkenswert an diesem Buch, das mich als junge Weberin inspirierte, ist die Tatsache, dass die Autorin, die nach dem Kriege aufbrechende, zumeist weiblich getragene, Weberei wie auch die Lausanner Biennale-Organisatoren unter dem Begriff Tapisserie subsumierte, obgleich die gezeigten Arbeiten nichts mit dieser kartongesteuerten Entwurfstechnik zu tun hatten. Kaufmann hatte als Deutsche in Berlin studiert, war 1938 nach England emigriert und 1947 nach New York gekommen. Das damalige europäische Selbstverständnis der Kunstgeschichtler, dass alles Textile mit Tapisserie zu tun habe, erreichte so auch die Neue Welt.

Es gab in den USA schon sehr früh Ausstellungen, die das Interesse fürs Textile anregten, so z. B. 1956 „Textiles“ im New Yorker Museum of Modern Art, mit auf die Industrieprodukte gerichteten Exponaten, aber auch einigen Stücken von Kunsthandwerkern, u. a. von Jack Lenor Larsen, der sich zwischen diesen Welten bewegte. Noch bevor sie in Zürich gezeigt wurde, hatte die Ausstellung ‘Woven Forms’ 1963 ihre Premiere im Museum of Contemporary Crafts mit fünf Teilnehmerinnen: Lonore Tawney, Alice Adams, Sheila Hicks, Dorian Zachai und Claire Zeisler. Im Jahre 1969 fand wieder im Museum of Modern Art die Ausstellung „Wall Hangings“ statt, ausgerichtet von Mildred Constantine und Jack Lenor Larsen. Vorgestellt wurden europäische und amerikanische Textilkünstler.

DIE ANFÄNGE IN EUROPA

Betrachtet man die Zeit nach dem 2. Weltkrieg, so gab es in vielen Ländern eine Rückbesinnung auf die Volkskunst,

so z. B. in Osteuropa und Skandinavien.

In Westeuropa waren Länder wie Deutschland und Österreich von der Blut- und Bodenideologie der Nazizeit beschwert und in Frankreich lastete eine staatlich-konservative Kulturauffassung auf dem Land. Andere Länder, wie z. B. die Niederlande, folgten den Entwicklungen in Nordamerika oder erlebten einen Aufbruch wie Großbritannien. Dort erneuerte sich die Textilkunst stärker auf dem Gebiet der Stickkunst und entwickelte sich dieser Zweig an den besten Universitäten zur Studiokunst.

Natürlich hatten die Biennalen von Lausanne seit 1967 großen Einfluss auf die textilen Künste Europas. Es entstanden nacheinander in den verschiedensten Ländern Biennalen oder Triennalen. Die niederländische Biennale „Werken in Textiel“ fand von 1968 bis 1973 dreimal statt. Die „Exhibition of Miniature Textiles“ in London, die zwischen 1974 und 1982 viermal ausgerichtet wurde, als Alternative zur für Künstler kostspieligen Lausanne-Biennale, wurde von 1976 bis 1983 fünfmal von der „Nordisk Triennial“ in Skandinavien gefolgt und sehr spät, von 1978 bis 1990, folgte die „Biennale der deutschen Tapisserie“ mit fünf Veranstaltungen.

Die Länder hinter dem Eisernen Vorhang hatten ihre eigenen Schaufenster zur internationalen Textilkunst: 1972 startete die „Internationale Triennale der Tapisserie“ in Lodz, im polnischen Zentrum der Textilindustrie. Diese Triennale existiert noch immer und richtet 2013 ihre 14. Auflage aus. 1975 war in der ungarischen Stadt Szombathely eine internationale Miniaturtextil-Biennale entstanden, die immer zusammen mit einer nationalen Tapisserieausstellung stattfand und zeitweise eine imposante Verbreitung fand. Nach der politischen Wende in Osteuropa wird diese Veranstaltung ab 2003 als Triennale weitergeführt.

Die Idee der Mini-Ausstellungen hat sich durchgesetzt. 1984 entstand in Strasbourg eine solche, die ab 1993 in Angers fortgesetzt wurde mit der 10. Auflage im Dezember dieses Jahres fortgesetzt wird. In Como begann der italienische Architekt Mimmo Totaro 1991 seine jährlich stattfindende internationale „Miniartextil“, die am 6. Oktober 2012 zum 22. Mal stattfindet und sich mit zusätzlichen Künstlereinladungen zur bedeutendsten Ausstellung ihrer Art etabliert hat.

TEXTILKUNST: ANDAUERN DER AMBIVALENZ

Die Entwicklung der Lausanne-Biennalen und ihr Ende hatten gezeigt, dass das Denken entlang der Tapisserietradition mit Blick auf die Kunstszene in einer Sackgasse endet. In Lausanne hatte man die Erfahrung machen müssen, dass für einige Künstler das Ausstellen zum Selbstzweck geworden war. Aus einem Gespräch mit Rebecca Medel aus den USA erfuhr ich, dass sie sich als größten Erfolg ihrer Kunst ein Museum vorstellte, das um ihr auf der 14. Biennale von 1989 vorgestelltes Werk herum konzipiert sei! Ich hatte sie zu meinem Erstaunen zu dieser Aussage animiert, weil ich von dem Werk „1000 Kannons“ fasziniert war, nur mir die Arbeit derart raumfüllend vorkam, dass mir ein adäquater Standort nicht eingefallen war.

Ich hatte schon damals mit vielen anderen Besuchern die Sorge, dass die Ausschreibungen zu den Biennalen am Wesen der Textilkunst vorbei gingen. Denn der Motor, der die textilen Künste antreibt, sind neben den Zielen, Sorgen und Hoffnungen der Gesellschaft, in der sie stattfinden, die Innovationen in Material und Technik, in der sich diese Gesellschaft zurechtfinden muss. Das Besondere bei Textil und Architektur ist die Auseinandersetzung mit diesen (jeweils neuen) Begebenheiten in veränderten Lebenslagen.

Wir schrieben 1989 nach einer der frühen Messen für technische Textilien in Frankfurt/Main mit Erstaunen, dass wir dort keine Textilkünstler und -designer angetroffen hatten. Denn bereits seit einigen Jahren waren eine Reihe wichtiger Neuerungen bekannt, die Michel Thomas schon 1985 in dem Buch „L’Art Textile“3) veranlasst hatte, von einer digitalen Perspektive der Textilkunst zu schreiben.

Zuerst wurde man in England auf die neuen Entwicklungen aufmerksam. Im Herbst 1994 zeigte der britische Crafts Council die Ausstellung „Textilien und neue Technologie 2010“, organisiert von Sarah Braddock und Marie O’Mahony, mit einem zur damaligen Zeit viel beachteten Katalog, dem 1998 das Buch „techno textiles“ folgte 4). Inzwischen ist dieses Gebiet zu einem Modethema geworden und hat von daher bereits wieder einen Teil seiner Wirksamkeit eingebüßt.

Auf der Messe Techtextil sahen wir auf fast allen textilen Teilbereichen faszinierende Neuentwicklungen, die erkennen lassen, dass wir einer Renaissance des Textilen entgegen gehen, was wir im ‘Manifest’ des 1991 neu gegründeten Europäischen Textil-Netzwerks (ETN) auch zum Ausdruck brachten. Diese alle zwei Jahre stattfindende Messe zeigt in Frankfurt und in den USA immer wieder neue Material- und Technologieentwicklungen, die von der kreativen Zunft der Textiler noch nicht einmal wahrgenommen werden, weil der Industrie der Kontakt zu den Künstlern abgeht und die Künstler Neuerungen auf ihrem Gebiet nicht sehr engagiert suchen. Es geht ihnen wie den Architekten im 19. Jh., die neugotische Rathäuser und Empire-Bahnhöfe entwarfen als die Ingenieure längst mit Konstruktionen aus Beton, Stahl und Glas beschäftigt waren.

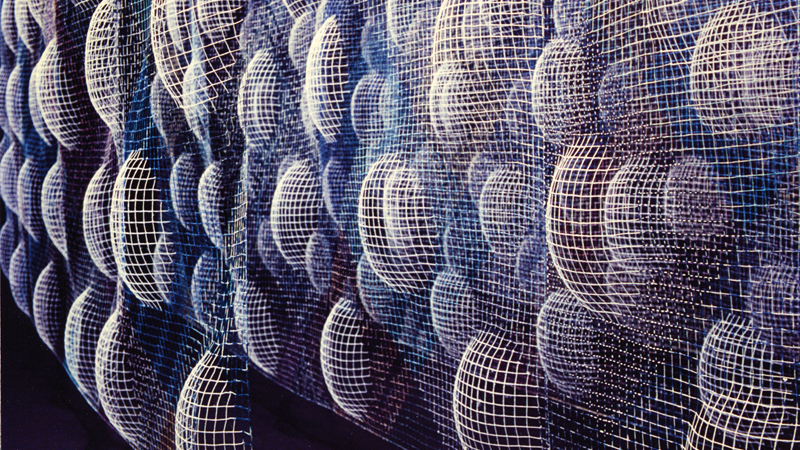

Lange vor dem Ende der Biennale hatte ein Aufschwung in der Jacquardweberei sogar schon unter Textilkünstlern stattgefunden. Die Webdozentin Alice Marcoux berichtete über ein Jacquardprojekt an der New Yorker Rhode Island School of Design, dessen Ergebnisse im März 1982 im Cooper-Hewitt-Museum ausgestellt waren und an dem namhafte amerikanische Textilkünstler teilgenommen hatten 5). Nicht zu vergessen ist die Schau „Textyles 1987“ in Paris, in der die französische Textil- und Modeindustrie erstmals einem breiten Publikum unter dem Motto „Die Mode, eine Spitzenindustrie (La mode, une industrie de pointe)“ ihre neuen Möglichkeiten präsentierte 6). 1991 hatte ich selbst im Rahmen unserer Kunst + Industrie-Projekte, teilweise mit denselben Künstlern, Untersuchungen an elektronisch gesteuerten Produktionsmaschinen in einer deutschen Weberei durchführen lassen, das den Teilnehmern die neuen Gestaltungsmöglichkeiten vor Augen führte 7).

Auf den Gebieten der Stickerei und des Textildrucks fanden in den 1980er Jahren weitere internationale Projekte und Konferenzen statt, die das Blickfeld weniger Textilkünstler auf die Zukunft der Textilkunst erweiterten 8) und die an den parallel verlaufenden Lausanne-Biennalen vorbeigingen.

AUSBLICK

Als interessierter Betrachter der Textilkunstentwicklung braucht man Geduld. Es hat schließlich ein Jahrhundert gedauert, bis auch die Architekten mit den neuen Materialien und Techniken vertraut wurden.

Der Boden für das Neue entsteht aus der Gesellschaft als Ganzer. Der Blickwinkel Aller muss sich erst ändern und die Wortführer müssen erst die neuen Phänomene zu benennen lernen, dass die Künstler dafür Formulierungen, d. h. Formen, ersinnen können.

Es würde helfen, wenn weitblickende Förderer der Künste, Wissenschaftler, Kunstpromotoren, Ausstellungsorganisatoren und Sponsoren für Gelegenheiten sorgten, den Weg der Künstler zu begleiteten, um deren riskante Suche nach neuen Formen zu unterstützen. Denn der Wandel der Formen, der erfolgen muss,

ist nicht allein Sache der Künstler.

Anmerkungen

Dieser Text ist in TEXTILFORUM 3/2012 erschienen.

1) Archives of American Art, Oral History, Interview mit Claire Zeisler im Juni 1981, http://www.aaa.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-claire-zeisler-12076

2) Ruth Kaufmann, „The New American Tapestry“, Reinhold Book Corp., New York 1968

3) Michel Thomas, Christine Mainguy u. Sophie Pommier, „L’art Textile“, Skira, Genf 1985, ISBN 2-605-00068-0 – M. Thomas gab zu jener Zeit die Zeitschrift Textile/Art heraus.

4) Sarah Braddock und Marie O’Mahony, „Textiles and New Technology 2010“, Artemis, London 1994 und „techno textiles-Revolutionary Fabrics for Fashion and Design“, Thames & Hudson, London 1998, ISBN 0-500-23740-9

5) Bericht in TF 1/1984, S. 29-31, Teilnehmer u. a. Lia Cook, Françoise Grossen, Gerhard Knodel, Ed Rossbach, Cynthia Schira

6) Michel Thomas veröffentlichte in seiner Zeitschrift „Textile/Art Industries“ den Katalog dieser Ausstellung der Cité des Sciences et d’Industrie

in der Jan./Febr. 1987-Ausgabe

7) Bericht in TF 3/1991, S. 25-40; Teilnehmer Lia Cook, Sheila O’Hara, Hanns Herpich, Patricia Kinsella und Cynthia Schira

8) U. a. die 1989 stattgefundene internationale Konferenz für Textildruck „PrinTX’89“ in Helsinki und des Stickworkshops mit US-amerikanischen und einer britischen Künstlerin/nen in der ZSK-Stickmaschinenfabrik in Krefeld (s. TF 4/1989, S. 26-34).

Weitere empfohlene Literatur: “Beyond Craft: The Art Fabric, Mildred Constantine / Jack Lenor larsen; Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 1973; ISBN 0-442-21634-3

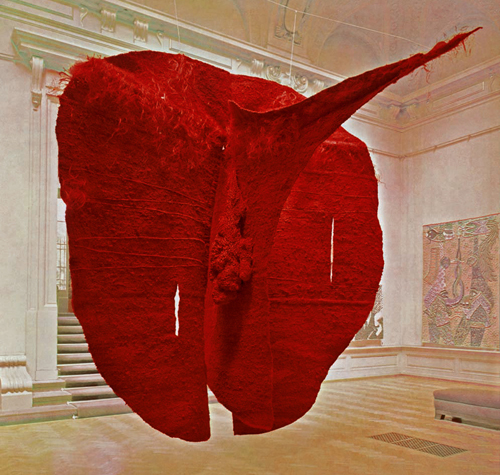

It was my privilege to exhibit opposite the great Magdalena Abakanowicz: in 1985. She exhibited some of here great Abakan pieces. I took part in the 12th Biennale International De La Tapisserie Lausanne with a paper and stitch installation ‘Sofonisba Anguissola.’ (One of a series of three installations marking ‘forgotten ‘ women artists.) Each panel was 6 feet in diameter. A postcard close up and the catalogue are sadly all that remain. I remember finishing some of the stitching to be attached to the piece whilst on the train travelling to Switzerland. .

thats great , thanks for great efforts http://goo.gl/tfeKBm