Fondation Toms Pauli. Sammlung des 20. Jahrhunderts.

Ausstellung vom 24. März bis 16. Mai 2016 im Musée Cantonale des Beaux-Arts von Lausanne, Palais de la Rumine

In den ehemaligen Ausstellungshallen der Biennale von Lausanne, im Palais de la Rumine, findet eine Ausstellung mit einer großen Vorgeschichte statt. Nachdem diese Biennale zuletzt 1995 nicht mehr im schönen Palais stattfinden durfte, hat der heutige Direktor des Kantonalen Museums für Bildende Kunst von Lausanne, Bernard Fibicher, die Stiftung Toms-Pauli als Erbe der Biennale eingeladen, seine zeitgenössische Sammlung wieder genau hier zu zeigen.

Welche positiven Veränderungen hat es gegeben?

Seit fast einem Jahrzehnt hat das Interesse an Textilkunst – seitens der Bildenden Kunst – so stark zugenommen, dass z. B. die letzten Biennalen von Venedig zu fast einem Drittel mit textilen Arbeiten bestückt waren. Dieses Phänomen zeigt sich auch bei Kunstmessen und großen Kunstausstellungen. Als Grund hierfür wird meistens angeführt, dass in unserer digitalisierten Welt das Haptische an Bedeutung gewinnt. Auch die sozialen Bezüge, die durch den Einsatz von textilen Mitteln so leicht sichtbar gemacht werden können, werden hervorgehoben!

Als die damalige Vereinigung Pierre Pauli mit der Stiftung Toms (historische Tapisserien) im Jahr 2000 zur Stiftung Toms-Pauli zusammengelegt werden konnte, bestand die Sammlung moderner Textilkunst aus 46 Werken. Heute besitzt die Stiftung über 200 Kunstwerke.

Die Toms-Pauli-Stiftung ist teilweise Erbe des CITAM (Fussnote 1). Die Werke der Sammlung – viele davon aus der Sammlung von Pierre und Marguerite Magnenat sowie der der Galeristin Alice Pauli, ergänzt durch Schenkungen von Künstlern und Mäzenen sowie durch Neuankäufe – gehören heute dem Kanton Waadt. Die jetzt gezeigte Ausstellung ist gewiss ein Glanzpunkt in der Vita der Stiftung!

Was ist in der Ausstellung ‘Tapisseries Nomades’ zu sehen?

Die Stiftung, die keinen eigenen Ausstellungsraum besitzt, hatte nicht die Absicht, eine komplette Retrospektive der Biennalen zu zeigen. Es werden lediglich 38 Arbeiten, die auf einer der 16 Biennalen zu sehen waren, aus der eigenen Sammlung der Stiftung gezeigt.

Die Absicht der Ausstellungsmacher war es, die Bemühungen der Pioniere der Neuen Tapisserie wie Jean Lurçat, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Jagoda Buić, Olga de Amaral, Elsi Giauque, oder Machiko Agano zu zeigen.

Die Ausstellung beginnt mit Arbeiten, die aus den sechziger Jahren stammen (Lurçat, Delaunay, Grau-Garriga). Sie wurden überwiegend in Wolle gearbeitet und waren Zeugnisse der Renaissance der Wandtapisserien, hergestellt in den großen Ateliers unter dem Einfluss von Jean Lurçat. Im Gegensatz dazu werden die Künstler aus Ost-Europa, die „neuen Barbaren“, die ihr Medium neu erfunden hatten, gezeigt. Sie gestalteten ihre Unikate selbst, oft mit ungewöhnlichen Materialien wie Sisal oder Hanf (Abakanowicz, Łaszkiewicz, Sadley ).

Ab Ende der sechziger Jahre beginnt die Eroberung des Raumes. Die Idee der klassischen Weberei für die Wand wird immer mehr zugunsten räumlicher Gestaltungen verlassen. Dabei beziehen Künstler sich manchmal auf die alten Traditionen ihres Landes (De Amaral). Andere verlassen die Technik der Weberei ganz und spielen in ihren Kompositionen mit offenen und geschlossenen Gestaltungen (Buić, Grau-Garriga, Daquin ).

Die siebziger Jahre zeigen außerdem immer verfeinertere textile Techniken (Cook, Matter) sowie poetische und symbolische Bezüge (Hicks, Giauque, Abakanowicz).

Ab Mitte der siebziger Jahre bringt die häufigere Teilnahme der Amerikaner und der Japaner eine neue Ästhetik. Die Künstler benutzen jetzt alle Arten von Fasern (tierische, pflanzliche, künstliche) auf sehr erfinderische Weise (Shaw-Sutton, Argano, Tanaka, Sitter-Liver). Aus Textilkunst wird, nach der amerikanischen Terminologie, Fiber Art.

Der Titel der Ausstellung „Nomaden-Teppiche“, bezieht sich übrigens auf eine Äußerung von Le Corbusier von 1960 über die Rolle der Kunst und der Tapisserie. Sie verweist auf die notwendige Komplementarität zwischen der Tapisserie und der Architektur. (Fussnote 2)

Die Tapisseriebiennale von Lausanne als Bühne für eine Revolution

Eine ungewollte Revolution hatte statt gefunden, von der klassischen Wandtapisserie zur frei gestalteten Textilkunst. Ungewollt deshalb, weil Jean Lurçat, als Initiator der Biennale, die reproduzierbare Tapisserie als Ziel seiner Bemühungen ansah. Die Veränderungen hin zur freien Gestaltung sah er mit gemischten Gefühlen: „Méfiez-vous des petites filles qui tricotent – hütet euch vor den kleinen strickenden Mädchen“ soll er gesagt haben, womit er die jungen ost-europäischen Künstlerinnen meinte, die mit revolutionären Unikaten an der Biennale teilnahmen. (Fussnote 3)

Die Revolution, die Jenelle Porter in ihrem Artikel „About 10 Years From the New Tapestry to Fiber Arts“ (Fussnote 4) in der Zeit von 1962 bis 1972 verortete, passte in den allgemeinen Aufbruch dieser Zeit, die auch eine neue Frauenbewegung hervorbrachte. Wie bei der textilen Revolution war ab der zweiten Hälfte der 70er Jahre auch in sonstigen gesellschaftlichen Bewegungen leider kaum noch Aufbruch festzustellen. Auf jeden Fall erhielten junge weibliche Künstler ab der ersten Biennale den meisten Beifall der Presse.

Wo kam dieser Aufbruch her?

Für Nord-Amerika sieht Jenelle Porter den ersten Schritt in der Einzelausstellung von Lenore Tawney1961 im Staten Island Museum, New York: “the point at which Art Fabric was healthfully and joyously launched in America“. Durch die Oral History Interviews mit Künstlern wie Tawney, Zeisler und anderen (Fussnote 5) kann man die Motivation erkennen: Zusätzlich zu der Auflehnung gegen die männlichen Künstlerkollegen wurde die Motivation genährt von den revolutionären Ideen der nach Amerika geflüchteten Bauhäusler sowie vom Rückbezug auf nicht-westliche Kulturen, zum Beispiel die großartige Südamerikanische Webkunst.

Dieses Interesse an der Ethnologie und der Volkskunst fand auch in Europa statt, am deutlichsten in den damaligen Ostblock-Ländern. Dort erhielten die Künstler, auch die der Angewandten Kunst, generell eine sehr gute Ausbildung. Da die Repressionen politisch ‘auf Linie’ zu sein für die Malerei und Bildhauerei sehr einengend waren, erhielten die Angewandten Abteilungen der Akademien Zulauf begabter experimentierfreudiger Künstler. So auch die Textilabteilung der Akademie der Bildenden Kunst in Warschau, wo Magdalena Abakanowicz bis 1954 studiert hatte, sowie die Akademie von Poznan, wo sie in den sechziger Jahren als Professorin unterrichtete. Sie wurde von Pierre Pauli, Kurator des Museums für Dekorative Kunst von Lausanne, entdeckt und eingeladen, an der 1. Biennale von Lausanne teilzunehmen. Für Europa wurde sie die große Leitfigur des Aufbruchs.

Die Bedeutung der Biennale von Lausanne – Eine kurze Geschichte!

Der Anfang lag bei Pierre Pauli und dessen Frau Alice zusammen mit dem Maler Jean Lurçat (1892-1966) auf der Suche nach einer Zukunft für die klassische Tapisserie. Sie gründeten das CITAM (Fussnote 1)1961. Die erste Biennale fand 1962 statt, die letzte (und 16.) Biennale 1995. Pierre Pauli´s Verdienst ist es gewesen, die besten Kuratoren und Dozenten europäischer Museen und Kunstakademien, die ein Interesse an der Tapisserie gezeigt hatten, um sich zu scharen.

Die erste Biennale zeigte überwiegend reproduzierbare Wandtapisserien bekannter Maler (z. B. Picasso, Le Corbusier), ausgeführt in den großen Ateliers (u. a. Les Gobelin, Aubusson) in Formaten von mindestens 12 Quadratmetern.

Im Laufe der ersten drei Biennalen änderte sich diese Ausrichtung. Junge Künstlerinnen aus Mittel- und Ost-Europa, die ihre Arbeiten selbst als Unikate herstellten, traten in den Vordergrund. Man nannte sie die „Tapisserie-Barbaren“. „The Tapestry of Tomorrow has been born in Poland!“ schrieb der Kunsthistoriker André Kuenzli, sehr zum Leidwesen von Jean Lurçat und weiteren klassischen Kartonmalern.

Die 4. Biennale von 1969 galt als der Zeitpunkt, wo der dreidimensionale Raum erobert wurde: Künstler wie Abakanowicz und Elsi Giauque befreiten ihre Arbeiten von der Wand und platzierten sie im Raum.

Ab etwa 1970 gestalteten die nunmehr überwiegend weiblichen Künstler ihre Arbeiten selbst und zwar ohne Karton und oft nicht mehr mit dem Material Wolle. Künstler wie Peter und Ritzi Jacobi, Sheila Hicks, Jagoda Buić, Aurèlia Muñoz oder Françoise Grossen schufen textile Skulpturen, oft mit ungewöhnlichen oder neuen Materialien.

Diese neue Bewegung war Anfang 1971 nicht mehr zu übersehen und man begann nach neuen Namen zu suchen: „Nouvelle tapisserie“ in Europa oder „Fiber Art“ in den USA. In verschiedenen europäischen Länder wurden ebenfalls Biennalen und Triennalen organisiert, z. B. die polnische Triennale ab 1973 (bis heute!), die Niederländische Biennale (1968-1974), die Nordische Triennale, die Biennale /Triennale von Szombathély und viele mehr.

Die 8. und 9. Biennale von Lausanne (1977, resp. 1979) waren durch Krisen gekennzeichnet. “Is it Still Tapestry?“ fragte sich Renée Berger, vice President des CITAM und Direktor des Museums der Bildenden Kunst von Lausanne.

Für die 11., 12., und 13. Biennale wurden Themen vorgegeben, respektive „Textil im Raum“, „Textile Skulptur“ und „Zurück zur Wand“. Die nun zuständige Direktorin des Museums für Bildende Kunst, Erika Billeter, sprach von Textilkunst. Diese Dreiteilung konnte die Krise jedoch nicht überwinden helfen. In ihrer Einleitung zur 14. Biennale (1989) schrieb Erika Billeter: „The heroes are worn out“ (…) The revolution of the weaver´s art has been over for a long time“ (die Helden sind müde… Die Revolution der Webkunst ist längst vorbei). Bei der 16. Biennale (1995) weigerte sich der damalige Direktor des Museums für Bildende Kunst, die in die Krise geratene Biennale zu beherbergen. Zu den neuen Ausstellungsorten kamen zu wenige Besucher, was die Stadt Lausanne als wichtigsten Geldgeber dazu veranlasste, die Veranstaltung zu schließen und das CITAM aufzulösen.

Persönliche Anmerkungen

In den 60er und 70er Jahren galt die Tapisserie-Biennale von Lausanne als leuchtendes Fenster zur Welt. Lausanne war das Mekka der Textilstudenten und angehenden Textilkünstler. Der Aufbruch dieser Zeit zeigte Parallelen, die für mich kein Zufall waren, nämlich die Gleichung „gute Zeiten für Frauen sind auch gute Zeiten für die Textilkunst“. Der spätere Niedergang war ebenfalls absehbar: Einige der späteren Kuratoren der Biennale vernachlässigten die spezifische Qualitäten und Vorteile der Textilkunst (z. B. die Beliebtheit beim Publikum). Sie richteten sich auschließlich auf einen engen Begriff der Bildenden Kunst, um die Rolle der weichen, faltbaren textilen Materialien in der Kunst neu zu bestimmen, in der Absicht die Textilkunst auf diese Weise aus dem Ghetto zu holen. Damit wurde die Veranstaltung beliebig, quasi die unbedeutende Schwester der Biennale von Venedig. Der Spruch „Die Künstler sind müde“ fiel ironischerweise genau zu dem Zeitpunkt, als die neue Revolution der digitalen Weberei anfing, gefolgt von der Revolution der neuen „smart materials“ und Techniken (wie das dreidimensionale Drucken). Ein Artikel in der Zeitschrift Textilforum zu diesem Thema ist lesenswert (Fussnote 6). Die textile Kultur sollte man als eigenständiges Kulturgebiet, ähnlich der Architektur begreifen. Textilkunst, die ausschließlich Kunst sein will, verleugnet jene haptischen und emotionalen Qualitäten, die die Bildende Kunst heute zu Anleihen bei der textilen Kunst veranlasst.

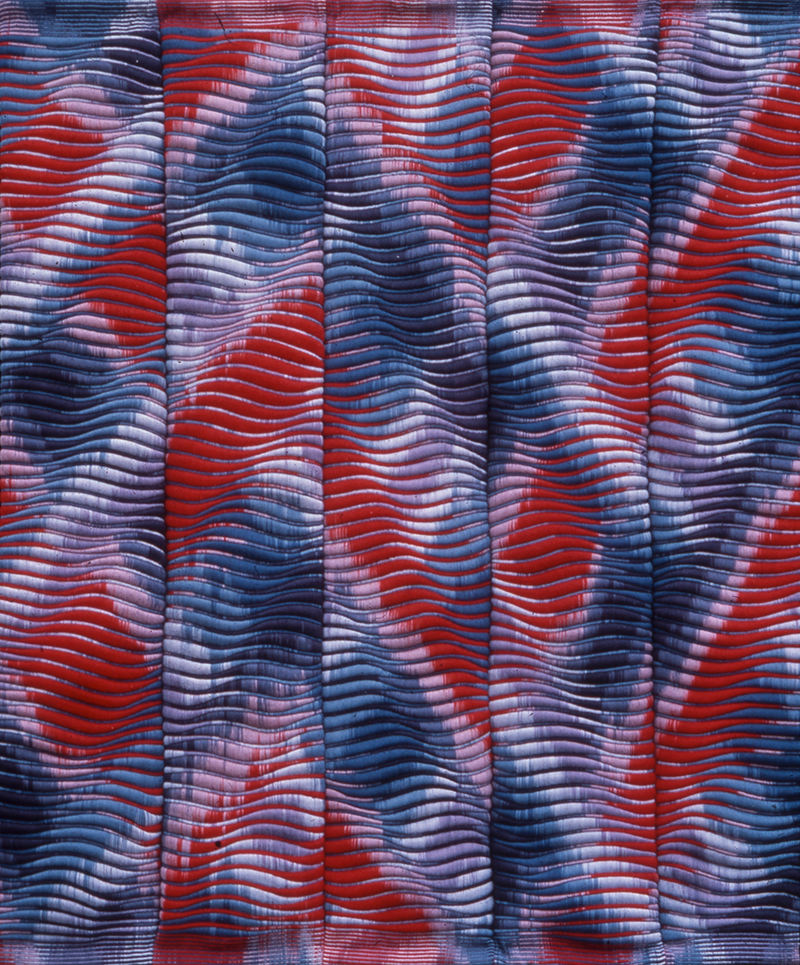

Die jetzt laufende Ausstellung war jedoch eine sehr positive Überraschung. Die Arbeiten, die alle zwischen 1960 und 1995 hergestellt wurden, strahlten Energie und starke Präsenz aus. Zwei Beispiele (von vielen), die mir sofort ins Gedächtnis kommen, sind „Red Abacan“ von Magdalena Abakanowicz und „Spatial Ikat“ von Lia Cook.

Das Publikum, das wieder in großer Zahl präsent war, war genauso begeistert wie während der originalen Biennale-Ereignisse. Gefragt nach neuen Plänen auf dem Gebiet der Textilkunst, waren sowohl der Direktor des Museums für Bildende Kunst wie die Kulturvertreterin des Kantons Vaud sehr positiv. Sie wollten aber warten auf das neue Museumsgebäude „pôle muséal“, das für 2019 geplant ist, wo sowohl die Toms Pauli Stiftung als auch das Museum für Bildende Kunst im selben Gebäude untergebracht sein werden.

Es gab keinen Katalog, dafür plant die Kuratorin Giselle Eberhard Cotton ein umfangreiches Katalog-Buch zu der Geschichte der Biennale von Lausanne, das 2017 publiziert werden soll. Viel Bildmaterial mit Arbeiten der Biennalen findet man auf der Internetseite der Stiftung (Fussnote 7).

Beatrijs Sterk

Ehemalige Herausgeberin der Zeitschrift Textile Forum,

heute Herausgeberin von https://www.textile-forum-blog.org

März 2016

Fussnote 1: Das CITAM oder Centre Internationale de Tapisseries Anciennes et Modernes (International Center for the Promotion of Ancient and Modern Tapestry) wurde 1961 in Lausanne gegründet. Gründungsmitglieder waren Jean Lurçat und Pierre Pauli.

Fussnote 2: „ce mur de laine qu’est la tapisserie peut se déchrocher du mur, se rouler, se prendre sous les bras á volonté, aller s’accrocher ailleurs. C’est ainsi que j’ai baptisé mes tapisseries ‘Muralnomad’“. Le Corbusier „tapisserie muralnomad in Zodiac, 7, Mailand, 1960

Fussnote 3: siehe Artikel von Dietmar Laue „Die internationale Tapisserie-Biennale von Lausanne 1962-1995“ in Textilforum 3/2012, S. 30-33

Fussnote 4 : Artikel im Katalog der Ausstellung „Fiber Sculpture, 1960 to Present“, die vom 1.10.2014 bis 4.1.2015 im Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, USA, stattfand

Fussnote 5: “Oral history interview with Claire Zeisler”, Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution, June 26, 1981 und Interview mit Lenore Tawney: http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-lenore-tawney-12309

Fussnote 6 : siehe Artikel von Beatrijs Sterk „Die Textilkunst“ in Textilforum 3/2012, S. 34-37

Fussnote 7 : http://www.toms-pauli.ch/ biennales/historique/