In recent years textile has increasingly become a medium of significance in the art world. In other words, the fibre arts are now being shown in many art exhibitions. Unfortunately, the work of those who actually call themselves fibre artists rarely appear in these, unless they saw their heyday some 40 or 50 years ago, in which case they are now elderly or deceased. Up until now, there have been mostly closed networks of ‘fine’ art and textile art exhibitions. However, an increasing number of artists who have started to use textile as a medium are being featured in textile exhibitions. This is rightly seen as an enrichment. Are the boundaries between fine art and fibre art blurring?

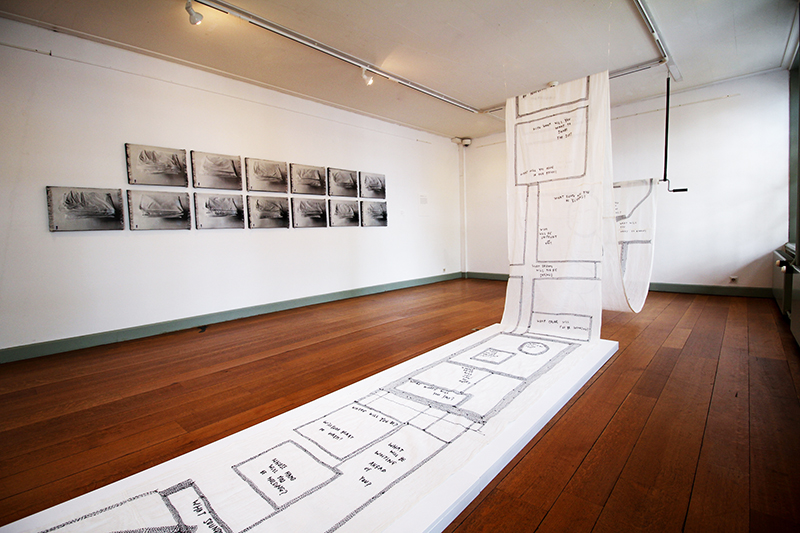

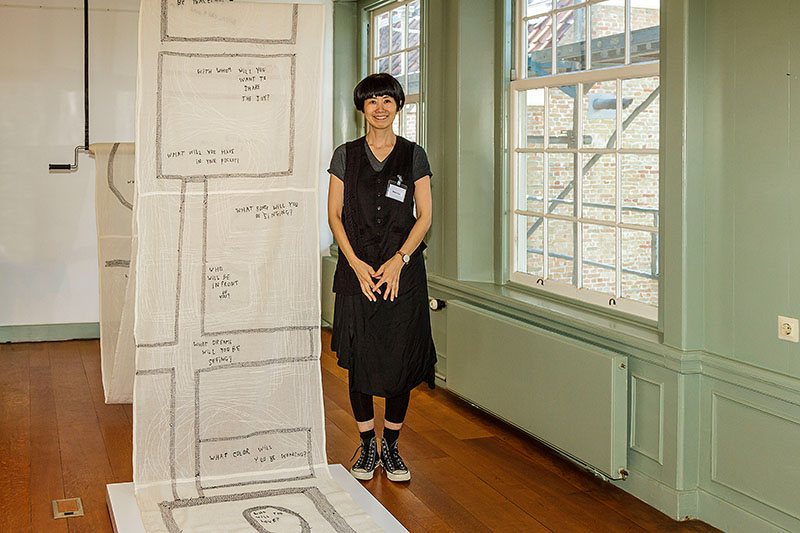

The Rijswijk Textile Biennial is a pioneer in this regard, because from the very first edition a mix of fine and fibre arts have been presented. This biennial developed logically from the Rijswijk Paper Biennial that had been organized by Museum Rijswijk since 1996. While in Dutch terminology the paper and textile arts are divided, in English they are united under the concept of Fibre Art. The Textile Biennials commenced in 2009 in order to ensure the inclusion of textile art.

The aim of both biennials is to show the innovative elements of contemporary textile and paper art, whether in artistic or material terms. By focusing on innovation, artists who are working in new and often surprising ways with textile form the majority in this exhibition: only 7 of the 24 artists selected this year are still connected to textile traditions and regarded as specifically textile artists. However, Museum Rijswijk with its Textile Biennials knows how to recognize and appreciate well-made textile art.

Textile art has long been considered the ‘unfortunate stepsister’ of the art world. It was seen as a craft, in which there was too much emphasis on the material aspects, making it unworthy as a medium for high-end artistic concepts. Also the fact that it was mostly work made by women did not help in raising its profile as an art form.

What do curators of textile art exhibitions say about their reasons for showing textile? Some are finished with all the ‘-isms’ of the 20th century. Others see that in today’s virtual world there is a strong desire for tactile things, objects that people can touch.

A highpoint was reached in 2014 in Europe, with various large-scale exhibitions featuring art and textile. In Wolfsburg, Germany there was the most important show: Art & Textiles (2013/14),1 which was comparable in size and period covered (from the beginning of the 20th century to the present) to the Decorum exhibition in Paris (2013/14).2 While the French curator drew on the tradition of tapestry-making and focused much attention on the Tapestry Biennials in Lausanne (held 1962 to 1994), the Wolfsburg show focused more on the influence of textiles on modern abstract art. The organizers of both shows emphasized that they wanted to break down preconceived notions about textile being the domain of women, about it being anachronistic, primitive and aligned with industrial endeavours. Their aim was, rather, to shed light on the vitality and sensual aspects – characteristics that are at risk of disappearing in the digital age. Sadly, the curators focused on the ‘big names’ in modern textile art and there was no room for contemporary fibre artists in either exhibition. Joanna Mattera, the former editor of Fiber Art magazine responded to this: “Don´t shoot the messenger, but it is pretty obvious to me that … the ‘fiber’ or ‘textile’ adjective is nowhere connected to artists who have broad art-world careers”.3

The organizers of the exhibition Fiber: Sculpture 1960 – Present (Boston, USA, 2014), with a catalogue edited by Jenelle Porter,4 were well-informed about textile arts. Porter and her female co-authors (to me, it’s no coincidence that women made this happen here) understood the extent of the revolution in textile art in the 1960s and 1970s. They saw that no one in their professional art circles ever discussed this and found it incomprehensible.

Porter attributed the discussion of textile art as sculpture (rather than crafting) to textile artist Lenore Tawney, who was doing so already in the 1960s. She wrote: “By 1972 the transformation of tapestry into a form known as ‘fiber art’ represented an expansion of the category of sculpture by a generation of artists who approached art making with radical new ideas”. This was the right approach, but one that unfortunately seemed to limit itself to the big names of the Lausanne Biennials. Again, the work of younger fibre artists was invisible (though a few young sculptors working with textile were included).

Over the past two or three years the big names among fibre artists from modern times have been given attention, in exhibitions such as those on Hannah Ryggen (1894-1970) in Oslo and Frida Hansen (1855-1931) in Stavanger. Leipzig held an exhibition on Johanna Schütz-Wolff (1896-1965), a German weaver comparable to Anni Albers. The Textile Room in Zürich showed the history of textile art in Switzerland, with well-known artists such as Elsi Giauque (1900-1984) and Sophie Tauber-Arp (1889-1943). More famous names from the Lausanne Biennial period were presented in Tapisseries Nomades, with works from the collection of the Toms Pauli Foundation in Lausanne. It was surprising to see that the works shown were as dynamic as 40 or 50 years ago.

The raised profiles of the leading players could mean that the history of modern textile art has been able to attract more attention in general. Contemporary fibre artists would then be the next generation to be in the limelight. Alas, it seems this isn’t going to be happening anytime soon. Sometimes there is hope on the horizon, such as when fibre artists themselves become active, as happened in Italy where a big exhibition was organized in the Museo Nazionale delle Arti e delle Tradizione Populari in Rome in 2015. OFF LOOM II came to fruition because they saw so much fibre-related art appearing in the Venice Biennials while not being given a part in these.

In the meantime, there have been exhibitions that included ‘art with textile’, though not so many. In An exploration of textiles as a medium for social, political and artistic expression in Manchester (2015), the usual mix of old and new names were shown: artists like Magdalena Abakanowicz, Tracey Emin, Grayson Perry, Ghada Amer and Kimsooja, who use textile as a medium to express their ideas on social issues, politics and art. Among the contemporary artists, once again there were no fibre artists. One American art critic noted “…the art world is obsessed with celebrity and money, and well-known artists are being over-estimated.”

A new ray of hope is this year’s art exhibition Entangled: Threads and Making at the Turner Contemporary in Margate (UK) 5 where, apart from famous names like Anni Albers, Louise Bourgeois, Sonia Delaunay, Eva Hesse and Hannah Ryggen, contemporary fibre artists are also being shown, such as tapestry weaver Maureen Hodge. On show are works by 40 different women “who have frequently drawn on the rich traditions of handwork and craft to create artworks that challenge established distinctions between fine art and applied art“.

The unification of the worlds of fine art and fibre art seems to be making progress, but there is still a long road ahead. Exhibitions like the Rijswijk Textile Biennial are an encouraging step in the right direction.

Beatrijs Sterk

Publisher of Textile Forum Magazine (1982-2014) and founder of the European Textile Network. www.textile-forum-blog.org

1. Exhibition Art & Textiles – Fabric as a Material and Concept in Modern Art from Klimt to the Present, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany, 2013/14.

2. Exhibition Decorum – Artist Carpets and Tapestries, Musée d´Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, France, 2013/14.

3. Joanne Mattera, ‘Fiber, Fiber Everywhere’ in Surface Design Journal, Fall 2013.

4. Jenelle Porter (editor): Fiber: Sculpture 1960 – Present, The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, USA, 2014.

5. Exhibition Entangled: Threads and Making, Turner Contemporary, Margate, England, 2017. Catalogue editor: Karen Wright.

This article was published in the catalogue of the Rijswijk Textile Biennial 2017; translation by Diana Beaufort