The 57th Venice Biennial is a feast for all those loving textiles! Visitors, who have seen it many times, are saying that never ever has there been so many textiles on show. This is not only true for the Biennale itself but also for the national pavilions!

Held since 1895, the Venice Biennial is the oldest biennial art exhibition in the world. Nevertheless it attracts fewer visitors than Documenta in Kassel (most recently, 500,000 at Venice in 2015, compared to 900,000 at Kassel in 2012). It is divided into two sections; firstly, the ‘Viva Arte Viva’ exhibition curated by Christine Macel, featuring 120 invited artists in the Giardini (gardens) and halls of the Arsenale; and secondly, exhibitions presented in 97 national pavilions located at the above exhibition venues and, in some cases, distributed across the city. According to the catalogue, an additional 23 events are being held at the same time, not to mention the many shows on display in almost every museum and gallery around the city.

Curator Christine Macel (born in Paris in 1969) is the chief curator of the Centre Pompidou. This is only the fourth time that a woman has been in charge of the exhibition. ‘Viva Arte Viva’ is meant to be ‘a passionate outcry for art and the state of artists’. The exhibition is divided into nine themed pavilions which point in a new direction: the Pavilion of Artists and Books, Pavilion of Joys and Fears, Pavilion of the Common, Pavilion of the Earth, Pavilion of Traditions, Pavilion of Shamans, Dionysian Pavilion, Pavilion of Colours and Pavilion of Time and Infinity.

Christine Macel‘s selection marks a departure from the critical political line espoused by the curator of the last Biennial, Okwui Ehwezor, but it still presents a fair amount of politically motivated art and utopias conceived from the Sixties to the Eighties. In some cases (such as Maria Lai and Geta Brătescu), the same artists were featured at Documenta with its current aim of presenting a highly political profile.

Textile Works

The previous Biennial was said to have included more women artists than ever before. The current edition is said to feature more textiles than ever before! There is also a large number of female artists, and the grand old ladies are strongly represented. An Artsy Editorial published on June 19, 2017 was entitled, ‘Why Old Women Have Replaced Young Men as the Art World´s Darlings’. It appears that time is up for the old men who decide what is art and what is not.

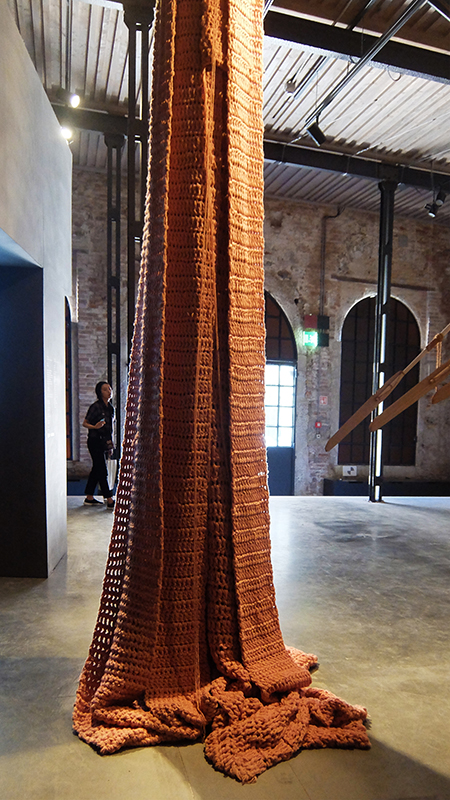

The crowd pleasers and eye-catchers of the Arsenale halls are made of textile materials. Firstly, a large installation entitled ‘A Sacred Place’ by Ernesto Neto, born in Brazil in 1964, is on view at the Pavilion of Shamans. Composed of various (crocheted!) nets, it forms a huge tent for visitors to enter and take a rest. In the Pavilion of Colors, Sheila Hicks, born in 1934, shows her 2016 installation, ‘Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands’. While certainly not the best artwork ever created by this artist, the piece still works beautifully in lighting up the dark Arsenale hall in all the colours of the rainbow. The works by Neto and Hicks are the most frequently photographed by visitors who, unlike art critics, are delighted by the Biennial.

Interactive works play a major part in the Biennial. My attention was drawn by two in the textile section: Lee Mingwei’s Mending Project in which he asks visitors to allow him to repair or embellish an item and engages them in conversation while doing so. Encouraging a sense of community and inviting visitors to open up, his work belongs in the Pavilion of the Common. The curator’s explanations in the catalogue are badly needed because the reasons for allocating artists to their various pavilions are not always as obvious as in this case. A work by David Medalla from Israel, entitled ‘A Stitch in Time’, was assigned to the same pavilion and also invites participation; originally created in 1968(!), it was revised for the Biennial in 2017. Visitors are asked to add personal items and notes to a hanging sculpture, an idea that is meeting with great enthusiasm.

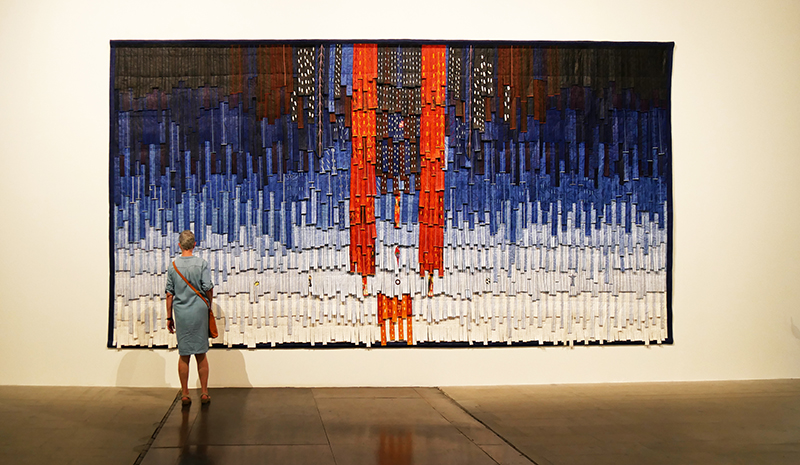

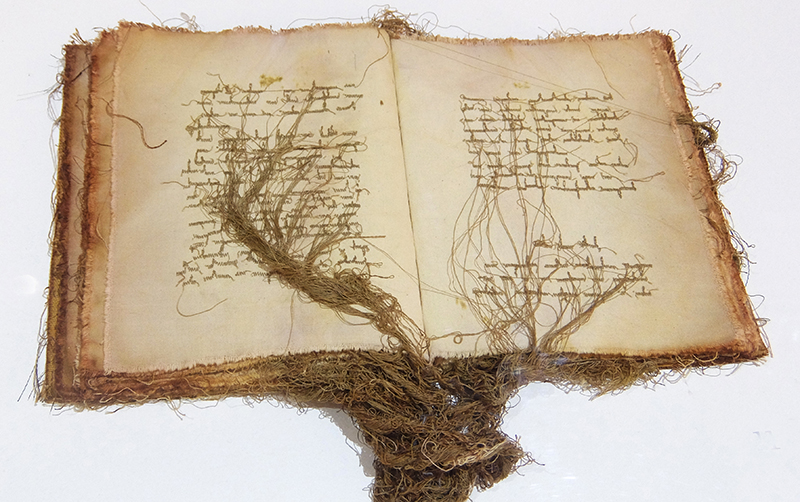

The ‘Viva Arte Viva’ exhibition features a considerable number of two-dimensional wall-based art which would have been well placed in any textile art exhibition. Examples are an appliqué piece inspired by Berber rugs created by Teresa Lanceta, born in Spain in 1951, or a huge half-relief tapestry sewn and embroidered in the appliqué technique by Abdoulye Konaté, born in Mali in 1953, which hangs in one of the best spots of the Arsenale halls.

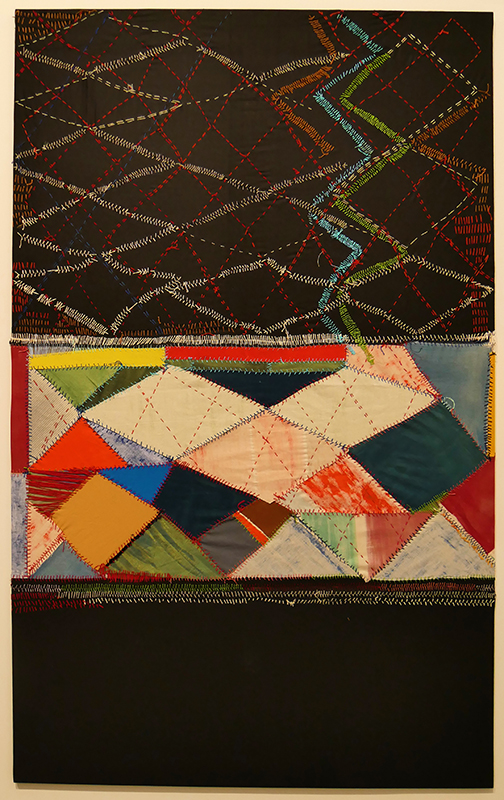

The pieces by Achraf Touloub, born in Morocco in 1968, look like highly innovative quilts. He creates them by using oils, graphite and paper on nylon and canvas.

These artists move in the orbit of the art scene and possess CVs to match, having participated in art biennials etc. Otherwise they would most likely not be represented in the show as the crafts are still subject to a taboo; achievements in this field are supposed to be recognised only 50 years after the event (when the artists are either dead or very old)!

Remarkably, this Biennial presents little in the way of fashion & clothing, despite the fact that this field was integrated into art at a very early stage. A great deal of clothing is scattered about the various installations featuring everyday objects, but there are few proper works of art. One example is the work of Huguette Caland, born in 1931, whose humorous mannequins date from 1985. The surreal figures by Francis Upritchard, born in New Zealand in 1976, appear to be from another world. They appeal to visitors who spend a long time standing in front of the individual figures, which obviously emanate an emotional power.

The pavilions most frequently mentioned are those of the United Kingdom, the USA and Japan. Mark Bradford was given the honour of designing the United States Pavilion. He has applied himself to his task with a zeal that leaves almost no air breathe. Entitled ‘Tomorrow is Another Day’, his exhibition creates a highly textile effect, especially in the entrance area where a large cloth is suspended from the ceiling, and in the first room presenting sculptures made from everyday materials. In her installation ‘Folly’, Phyllida Barlow from the United Kingdom has created an overwhelming variety of sculptures, some made from textile materials and some from papier-mâché stretched across wires. Her work was on display at the Turner Contemporary during the ‘Entangled: Threads and Making’ exhibition last spring. She, too, likes to use everyday materials, questioning old ideas on what sculptures are meant to look like. Born in 1944, she is one of the ‘old women’ who have lately been given centre stage.

The Japanese Pavilion was designed by artist Takahiro Iwasaki and entitled ‘Turned Upside Down, It’s a Forest’. Its centrepiece is an installation of old clothes, and visitors who put their heads through a hole unexpectedly become part of the installation.

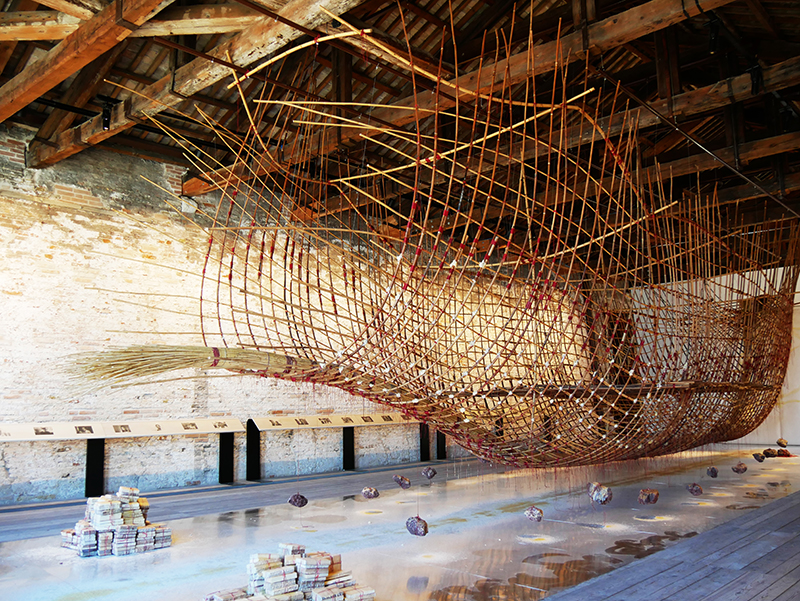

For the Singapore Pavilion, artist Zai Kuning has created a ship once navigated by the first Makay king in South East Asia which is very impressive, albeit somewhat out of the way. The gigantic bamboo structure generates a sense of lightness and poetry.

Many other textile pieces could be mentioned at this point, for instance a crocheted and knitted piece exhibited at the Pavilion of Artists and Books entitled ‘In Between the Lines 2.0’ by Katherine Nuñez and Issay Rodriguez, born in the Philippines in 1992 and 1991 respectively; or the very large canvas works which nevertheless do not create much of a textile effect by Franz Erhard Walther, born in Germany in 1939.

Generally speaking, the Venice Biennial is a feast for the eyes. It felt good to see so many textiles presented so naturally in an art exhibition of such importance. Visitors who have attended several previous editions say that the rather more cheerful appearance of the – usually rather gloomy – halls this time is due, not least, to the many textiles.

Beatrijs Sterk

Hanover, June 24, 2017