Der erste Teil dieser großen Übersichtsausstellung mit textilen Arbeiten von Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930 – 2017) findet vom 30. November bis zum 1. April 2018 im Textilmuseum in Łódź in Polen statt. In dieser Ausstellung sind 21 Arbeiten zu sehen, von denen 12 aus der Sammlung des Textilmuseums selbst stammen, 5 aus der Magdalena Abakanowicz Stiftung, die von ihrem Mann geleitet wird. Weitere 2 Arbeiten stammen aus dem Nationalmuseum in Wrocław und 2 aus der Galerie Starmach. Diese Arbeiten zeigen die textile Revolution in Polen nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg in Kurzform!

Die Entstehung einer textilen Revolution im Ostblock lässt sich vielleicht so erklären: Damals in der sowjetischen Zeit gab es – nicht nur in Polen – viele sehr gut ausgebildete Künstler, die nicht in die Abteilungen für Malerei und Bildhauerei eintraten, weil sie dort strenger überwacht worden wären als bei den sogenannten angewandten Künsten. So waren auch die Textilabteilungen der Kunstakademien mit sehr hoch qualifizierten Künstlern besetzt, die hier ihre Freiheit auslebten. Diese müssen nicht allesamt gegen das Regime gewesen sein, aber sicher sammelten sich hier die rebellischen Naturen. Magdalena Abakanowicz wurde durch ihren Erfolg jedoch zum Liebling des Regimes, wie auch die großen Sportler! Sie soll damit sehr vorsichtig umgegangen sein.

Die Kuratorin der Ausstellung, Marta Kowalewska, wollte die Anfänge zeigen. Wie kam es zu den ‘Abakans’? Sie sieht die Zeit, als Abakanowicz Tapisserie herstellte, als die wichtigste in ihrer Karriere. Damals war das Medium der Tapisserie noch mehr verbunden mit der Architektur und der dekorativen Kunst. Zusammen mit einer Gruppe polnischer Künstler gehörte Abakanowicz zu den ersten, die alle Regeln brachen und Tapisserie wie eine eigenständige Kunstform behandelten. Sie fing ihr Studium in Sopot bei Danzig an und wechselte dann auf die Kunstakademie von Warschau. Abakanowicz war von Professor Mierczyslaw Szymanski inspiriert, der Tapisserie anders behandelte. Er lehrte seine Studenten verschiedene Strukturen zu gestalten und behandelte die Tapisserie wie Szenographie, wobei verschiedene Materialien wie Holz, Papier, etc. eingesetzt werden konnten. Abakanowicz war nicht direkt seine Studentin. Sie studierte jedoch an derselben Akademie, kannte diese neuen Ideen und scheint beeindruckt gewesen zu sein.

Die Ausstellung folgt der Entwicklung von Abakanowicz. Das erste Ausstellungsstück ist eine Gouache auf Baumwolle, frei hängend ohne Rahmen. Es sieht sehr textil aus! Es scheint auch andere Künstler gegeben zu haben, die so arbeiteten, aber Abakanowicz hatte ihren eigenen Stil, meistens mit biologischen Elementen. Die Natur war ihr immer sehr wichtig.

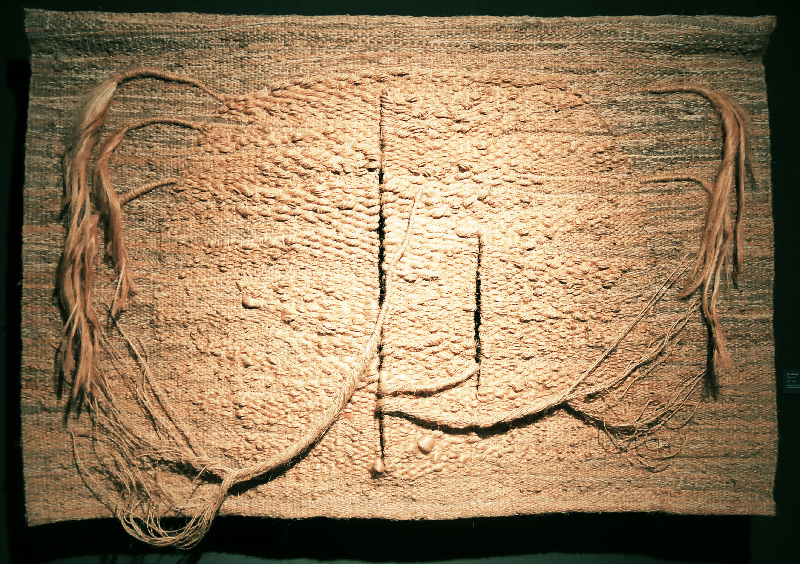

Ab Anfang der 60er Jahre stellte Magdalena Abakanowicz auch flache wandbezogene Tapisserien mit vielen dreidimensionalen Strukturen, zumeist in Linen , Wolle und Baumwolle ausgeführt, her. Von großer Bedeutung war die erste Biennale von Lausanne 1962, an der 5 polnische Künstler mit sehr ungewöhnlichen Arbeiten – in verschiedenen Materialien und Strukturen – teilnahmen. Die von Abakanowicz eingereichte Arbeit ‘Composition of White Forms’ wurde in der Werkstatt von Maria Makiewicz an einem 2 Meter breiten Webstuhl hergestellt. Da die Arbeiten 12 Quadratmeter groß sein sollten, entstand diese Tapisserie im ungewöhnlichen Maß von 2 mal 6 Metern! Da die polnischen Künstler das Geld für das Material nicht hatten, schaltete die Direktorin des Museums für Geschichte der Textilindustrie (ab 1975 umbenannt in das Zentrale Textilmuseum), Krystyna Kondratiuk, das Kulturministerium ein, was ein sehr ungewöhnlicher Vorgang war. In dieser Arbeit waren Kette und Schuß aus Baumwollkordel in der Farbe weiß, jedoch in verschiedenen Abstufungen.

Jean Lurçat, der Initiator der Biennale von Lausanne, soll sich sehr darüber aufgeregt haben, dass es so viel Interesse für diese neue polnische Webkunst gab. Dies war nicht in seinem Sinne. Er hatte an eine Biennale für Kartonmaler gedacht, wobei professionellen Webern die Ausführung zugedacht war. Diese neue Richtung, wo die Künstler selbst webten, kam ihm in die Quere!

Sehr wichtig für Abakanowicz und die polnischen Weber war der Besuch von Pierre Pauli (Mitbegründer der Biennale, Errichter und erster Kurator des Musée des arts décoratifs de Lausanne) und André Kuenzi (Kunstkritiker) in Polen. Von letzterem stammt der Satz ‘The tapestry of tomorrow was born in Poland (Die Tapisserie von Morgen ist in Polen entstanden)’. Sie organisierten eine Ausstellung mit polnischen Künstlern, die als Wanderausstellung durch Europa zog und dadurch diese neue Richtung bekannt machte.

Die Arbeit ‘Desdemona’, die Abakanowicz für die zweite Biennale von Lausanne einreichte, war für ihre Entwicklung sehr wichtig. Sie setzte nun auch Pferdehaar ein und arbeitete immer mehr dreidimensional. Diese Arbeit war Teil eines größeren Zyklus von Tapisserien, die 1965 zur Biennale von Sao Paulo eingeladen wurden. Dort gewann Abakanowicz die Goldmedaille, was für ihre Karriere sehr wichtig war.

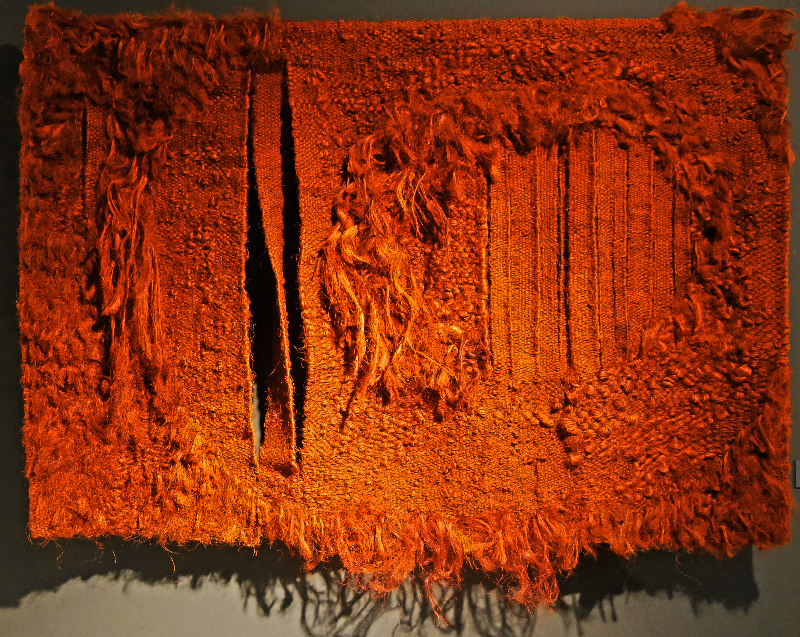

1968 brachte Abakanowicz ihre großen ‘Abakans’ in die Dünen bei Łeba an der Küste Polens. Ein Film von Kazimierz Mucha, der damals entstanden ist, ist Teil der Ausstellung und zeigt die ‘Abakans’ als große zoomorphische Gestalten, die sehr lebendig aussehen. Der Film wird von Musik, komponiert von Bogusław Schäffer, begleitet. Schäffer war Teil einer damals ähnlich revolutionären Gruppe von Musikern, die ebenfalls alle Regeln brachen.

Der mittlere Raum dieser Ausstellung hängt voll mit großen ‘Abakans’, die in kleineren Teilen auf einfachen Rahmen hergestellt und dann aneinander genäht wurden. Auf diese Weise brauchte es keine großen Ateliers, und es konnten leichter dreidimensionale Strukturen eingewebt werden. Zu dem großen braunen ‘Abakan’ aus dem Besitz des Textilmuseums sagt die Kuratorin, dass Abakanowicz in den USA oft wegen der Vulva ähnlichen Strukturen als Feministin angesehen wird. Sie sieht die Situation differenzierter, weil die Frauen im ehemaligen Ostblock sehr emanzipiert waren (z. B. größtenteils berufstätig) und andererseits weil Abakanowicz immer von der Natur und von den Formen, die sich organisch aus der Weberei ergeben, ausging!

Die Ausstellung endet mit jenem Zeitpunkt in der Entwicklung von Magdalena Abakanowicz, als sie anfing, menschliche Figuren aus Jute und Leinwand zu gestalten, um 1975. Ich bin auch der Meinung, dass diese erste Phase von 1960 bis circa 1975 die wichtigste für die Befreiung der Textilkunst aus alten Zwängen war. In dieser Ausstellung wird demnach eine textile Revolution sichtbar gemacht! Nichts weniger war die Absicht der Ausstellungsgestalter!

Auf meine Frage nach unbekannten Fakten im Leben von Abakanowicz sagte die Kuratorin Marta Kowalewska, dass viele nicht wissen, dass Magdalena Abakanowicz ihren Abschluss in Jacquard gemacht und auch in einer Seidenfabrik in Milanówek (Krawatten) gearbeitet hatte. Dies steht nirgends in ihrer Biografie, vielleicht weil es das Kunstimage der Künstlerin stören könnte? Weitere Anekdoten (überbracht von Kollegen) über Abakanowicz besagen, dass sie es auch gar nicht mochte, von Textilkünstlern angesprochen zu werden. So soll sie – während einer Einladungsreise für polnische Textilkünstler nach Israel – ausschließlich mit ihrer Assistentin und mit ihrem Mann gesprochen haben! Unsere großen Idole der Textilkunst hatten (und haben) ihre Schwächen!

Der zweite Teil der Ausstellung wird hauptsächlich aus Arbeiten aus der Sammlung der Stiftung Toms-Pauli in Lausanne bestehen. Sie findet vom 10. Mai bis 2. September 2018 wieder im Textilmuseum von Łódź in Polen statt. Ich will hiermit allen Textilkunstinteressierten einen Besuch dieser beiden Ausstellungen herzlich empfehlen, denn so viel Abakanowicz wird es nicht oft geben!