The-rhythm-of-Zen.blog_.jpg)

On view from 25 to 30 August 2018, this exhibition at the Academy of Arts and Design, Tsinghua University, China, was curated by Kai (Kelly) Liang. Previously she had travelled to nearly twenty countries and regions in Asia, Europe, North America and South America and interviewed more than a hundred textile artists. Based on these artist interviews, she wrote a comprehensive doctoral thesis of 300,000 words.The exhibition presented her selection of artists and strongly supported her doctoral research. Her approach (notions of care, well-being, femininity) is very different from what I saw and heard in my capacity as publisher of Textile Forum magazine in the past few decades. This is why I decided to publish her catalogue introduction here, and to illustrate some of the works she selected. Her writings made me think about what I regard as textile art, and I now realise that we need a complete history of modern textile art, from its beginnings in the early 20th century through its revival during the 1960s and 1970s up to the present day, written by those who experienced it in their own countries and continents.

Beatrijs Sterk

And-So-New-Stories-Are-Formed.a.blog_.jpg)

Guest editor Kai Liang (from the catalogue):

The term Fiber Art first appeared after the 1950s, a result of artists experimenting with soft and flexible materials; a momentum developed in the United States followed by the Nouvelle Tapisserie Movement in Europe which took place from the 1960s to the 1970s. The Swiss Lausanne Biennial (1962-1995) was a nucleus and the epitome of innovative international fiber art, where artists could showcase their experimental and original Fiber Art creations.

The development of Fiber Art can be divided into two principal periods. The first spans the 1960s to the 1980s. The second covers the 1990s to the present.

Greatly influenced by modernism, artists in the 1960s sought to improve awareness of the significance of Fiber Art by exploring material and formal possibilities. These artists disregarded associations to handcraft, femininity and domesticity, and instead highlighted the material and formal connections between their work and that of acclaimed Fine Art.

After twenty years of intensive creative development, Fiber Art was unable to find refuge in the simple impact of materials and their formal innovations. The 1980s introduced a period of self-examination and retrospection. Gerhardt Knodel gave an overview of the evolution of fiber art at this time:

The exploration of formal possibilities has been the focus, and often the heart of the movement. But today, in all aspects of art, there are broader issues of concern that relate life and art. How are the conditions of our time reflected in fiberworks? [1]

With the end of modernism, Fiber Art became one of the most conspicuous dead ends in the history of modern art [2]. The end of the Lausanne Biennial in 1995 marked the beginning of a post-Fiber [3] era. Where should it go after Fiber Art is accepted and considered as art?

This exhibition examines Fiber Art from the perspective of Care narrative. The term care refers to the ethics of care, which originated from feminist philosophers. Carol Gilligan first drew parallels between caring and connection in her thesis “In a different voice” [4]. Several notable care ethicists present varying views on the ethics of care in an attempt to construct an integrated system of care theory. The ethics of care centers around people as relational individuals and concerns itself especially with having caring relationships. Fiber Art is often made of soft materials and related to handcraft, domestic production and women’s work which lends itself to the consideration of warmth, benevolence and care, wherein lies the locus and identity of Fiber Art. As Holland Cotter said, fiber artists should always know that the fiber materiality with all its gravity, responsiveness and connections to life holds the tremendous capacity to speak to the issues of our human condition.[5]

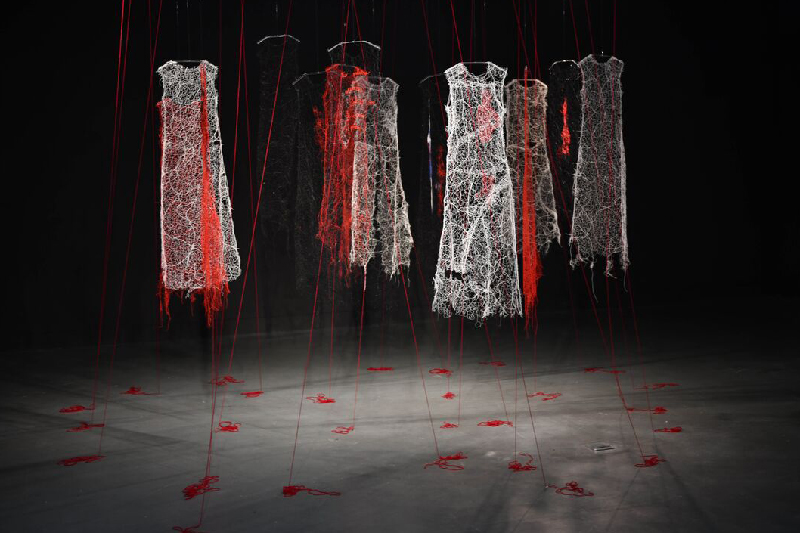

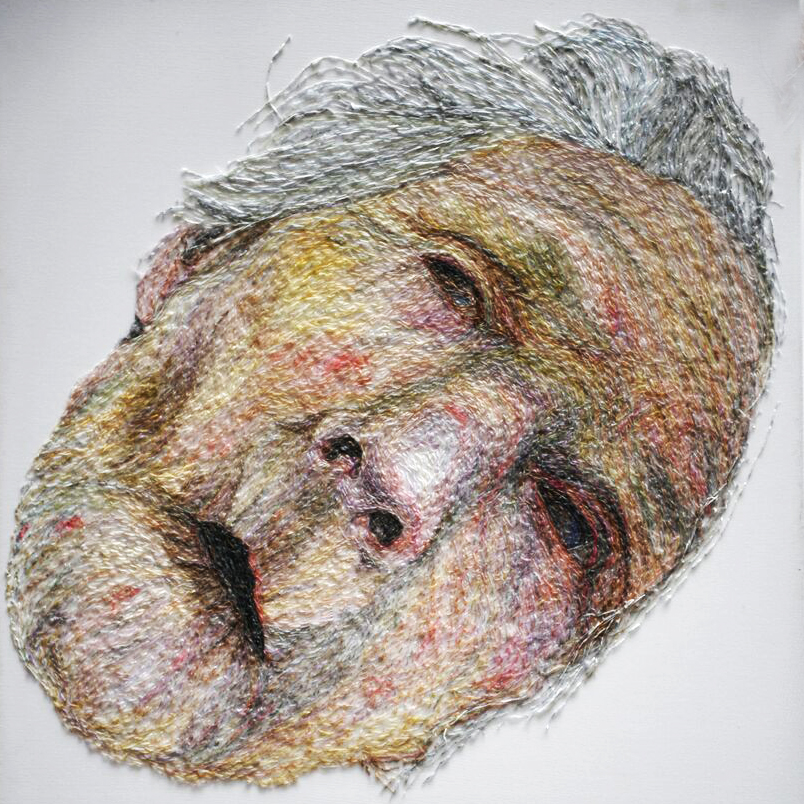

Twenty artists from ten countries were invited to show their artworks in this exhibition which collectively explore various aspects of the care narrative in Fiber Art. Monique Lehman and Xuefang Liang’s works consider the relationship between humans and nature. Jenni Dutton and Jo Hamilton’s works are about caring for aging and sick people. Susan Taber Avila focuses on well-being and self-care. Xingyu Hong and Lei Dai also promote well-being through their’s interactive artwork that encourages the viewer/participant to relinquish obsessions with the digital and virtual in favor of a material and physical practice. Line Dufour, Marie Bergstedt and David Catá make use their own life experience and emotions as the basis for producing narrative content. Carmen Imbach Rigos and Muñoz Torregrosa present family relationships and issues of femininity and domesticity. Masuma Khwaja Halai and Jovita Sakalauskaite speak to global cultural integration and contemporary society. Jian Wang and Yumei Zhou’s elucidate issues surrounding our consumer-oriented society. The works of Lecheng Lin and Nancy Kozikowski’s embody respect for weaving traditions. Joan Schulze and Wei Li forge their own unique path with their poetic Fiber Art expressions.

As a form of artistic expression of care, contemporary Fiber Art provides a constructive way of thinking and possible solutions to issues between humans and nature, humans and society, and humanity itself. Fiber and Care provides a new reference for the future development and theoretical construction of Fiber Art. As seen by the examples shown here, Fiber Art has its own authentic voice and is an essential component of contemporary Fine Art.

by Kai Liang

[1] Charles Talley, The Lausanne Biennale: an interview with Gerhardt Knodel , Surface Design Journal, May 1989, pp.14-21

[2] Glenn Adamson, The Fiber Game , Textile, 01 August 2007, Vol.5(2), p. 171

[3] Elizabeth Bacon Eager, Fiber: Sculpture 1960–Present, The Journal of Modern Craft, 04 May 2015, Vol.8(2), p.255

[4] Carol Gilligan, In a Different Voice, Harvard University Press,1982

[5] Giselle Eberhard Cotton, Magali Junet, From Tapestry to Fiber Art: The Lausanne Biennals 1962 to 1995, Skira, Milan/ Fondation Toms Pauli, Lausanne, 2017, p.19

Eye.a.blog_.jpg)

Seven-Impul…cstasy-details.blog_.jpg)

Rainforest.aa_.blog_.jpg)

The-Lines-of-my-hands.a.blog_.jpg)

The-Lines-of-my-hands-detail.a.blog_.jpg)

Float.blog_.jpg)

Light-at-the-end-of-the-tunnel.a.-1.jpg)

Contemporary-Fable-–-Horse.blog_-1.jpg)