The Lodz Triennial is currently the oldest textile art event in Europe and probably the whole world. It was created in 1972 as an East European window on textile art for all those who were barred from attending the Lausanne Biennial. The event was limited to Poland in its first year, but then opened to international participants. Until recently, the selection for this important exhibition – which always conveyed the notion of “tapestry” in its title – was undertaken by consultants in each country, so there was no public call for entries. This approach was subject to strong criticism, more so as it was often the same people who would act as consultants over long periods of time.

The Lodz Triennial is currently the oldest textile art event in Europe and probably the whole world. It was created in 1972 as an East European window on textile art for all those who were barred from attending the Lausanne Biennial. The event was limited to Poland in its first year, but then opened to international participants. Until recently, the selection for this important exhibition – which always conveyed the notion of “tapestry” in its title – was undertaken by consultants in each country, so there was no public call for entries. This approach was subject to strong criticism, more so as it was often the same people who would act as consultants over long periods of time.

Now a revival has been initiated to take account of the fine art community’s renewed interest in textiles. Finally there is an open call for entries and a curator belonging to the younger generation, Marta Kovalevska. Her intention is to put the focus on iconography and the new media. The idea is to address young artists as well as artists who work outside the field of textile art: “Young artists do not think that textiles are just a craft… they use the medium to discuss problems of our time” and “to place textile art in a contemporary context, you need to prompt artists to explore the hottest and most relevant topics of today”. Overall, Marta Kovalevska sees “textile art as an important genre of contemporary art.”

The overarching theme chosen for the event, “Breaching Borders”, was divided into seven theme sections: Migration and Cultural Identity, Physical Identity and Sexuality, Origins, Memory, Psyche and Dialogues all related to crossing boundaries in these fields. This structure worked very well. It made for a clearer presentation and emphasised the value of each work. New technologies and a revival of craftsmanship were further objectives. Nevertheless, this area lacked important techniques such as 3D printing, which has already shown art tendencies in design.

The choice of judges, the most influential of whom work in fine art, was probably designed to strengthen the inclusion of fine art. They included Anne Coxon, a curator at the Tate Modern; Michal Jachula of the Zacheta National Gallery of Art; and Mizuki Takahashi of the Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile, Hong Kong, who studied art history at the University of Tokyo.

Although the resulting selection was of a high quality, it obviously did not quite meet the expectations of the audience. Some of the older visitors said they had “seen it all before”, meaning that there was a lack of exciting new work. Others criticised a certain emptiness in the exhibition compared to the previous edition – an emptiness not simply arising from the fact that works had been hung more spaciously in this show. The selection probably did not quite achieve the richness of, say, the 2017 Triennial. How could this happen, and what were the causes?

Firstly, the time available had been very short. The new conditions for entry were only announced just over a year ago. Although the news spread quickly via the social networks, the demanding theme of “Breaching Borders” took a certain amount of time to digest, and perhaps could not be realised quite so quickly.

Another reason for the not wholly satisfactory outcome was and certainly still is the fact that well-known artists in particular prefer to be invited and rarely enter submissions of their own accord. I put this question to a number of artists, and they confessed that they had not submitted works.

Several artists had submitted work that had already been shown in other important exhibitions (including works by Kristina Daugintyté Aas and Sarah Perret); this should not have been allowed as it detracts from the importance of the International Lodz Tapestry Triennial.

I felt that another reason was the focus on young artists who, as newcomers, might come up with fresh ideas but would not be expected to create masterpieces from the outset. Moreover, participation was very unequal in terms of geographic distribution. It was obvious that all the Polish educational institutions were well aware of the Triennial having been restructured, but this did not seem to be the case in other countries. 22 of the 57 participants were from Poland and seemed rather young. The other countries were only represented by a very few participants – five from France, three each from the USA, Denmark, Germany and Israel, and two each from Japan, Finland and Canada. There was only one participant from each of the other countries. It is highly unlikely that good young textile artists can only be found in Poland!

The fact that the judges specialise in “fine art” may be a further reason for the imbalance in the selection. Of course, such people are well versed in what goes on in art. However, they often lack expertise when it comes to textile art. Back when the exhibition, “Entangled – Threads and Making” was held in Margate, UK, the mood was one of “rediscovery of the textile world”, but textile art experts such as Lesley Millar or Pennina Barnett, who have been involved in textile art all their lives, had not even been invited. This almost subconscious arrogance on the part of art curators is typical of the underappreciation of textile art which often requires specific knowledge or experience.

In this regard, my opinion on the need to renew textile art differs from that of the curator. I agree with her on the use of new technologies and a reassessment of craftsmanship, but I do not believe that changing the iconography to embrace more important topics is the solution. We did all that back in the late 1980s, when Gerhard Knodel (then a professor at Cranbrook) sat on the Lausanne jury. The statements written at the time were oh so important, and in fact often seemed more important than the works themselves. Textile art was no longer supposed to relate only to textiles, but rather to embrace specific themes, preferably socially relevant ones. At the time, this trend represented a kind of renewal of the Lausanne Biennial but did not serve to extend the life of that Biennial.

It would be a pity if the Lodz Triennial went the same way because we could use a renewal of the event, but one that maintained greater independence from fine art and kept in mind the idiosyncrasies and specific qualities of textile art.

What are the special features of textile art compared to so-called “fine art”?

I took another look at the various works in the catalogue and identified some ten works that belong to the field of fine art. They include the winner of the third prize, “3eme Age (le retour d’Ulysse)” by Aurélia Jaubert, which consists of pieces of embroidery discovered at flea markets and joined together like a patchwork. Another is “Totem” by Judy Hooymeyer which presents a stack of old woollen blankets. Viewers only know after reading the accompanying text that they relate to Inuit children taken away from their families, called the “lost generation”. In both cases, the association with textiles is purely coincidental, and the works do little to enrich textile art.

Another interesting piece is a large tapestry by Eva Nielsen entitled “Lucite” and woven in the Patrick Guillot studio (which belongs to the Cité Internationale de la tapisserie). Ever since Lausanne paved the way for the principle of “design and execution from one source”, such works were no longer displayed in textile art exhibitions. However, as fine art is constantly being produced by persons other than the artists, this divided working method is being seen again.

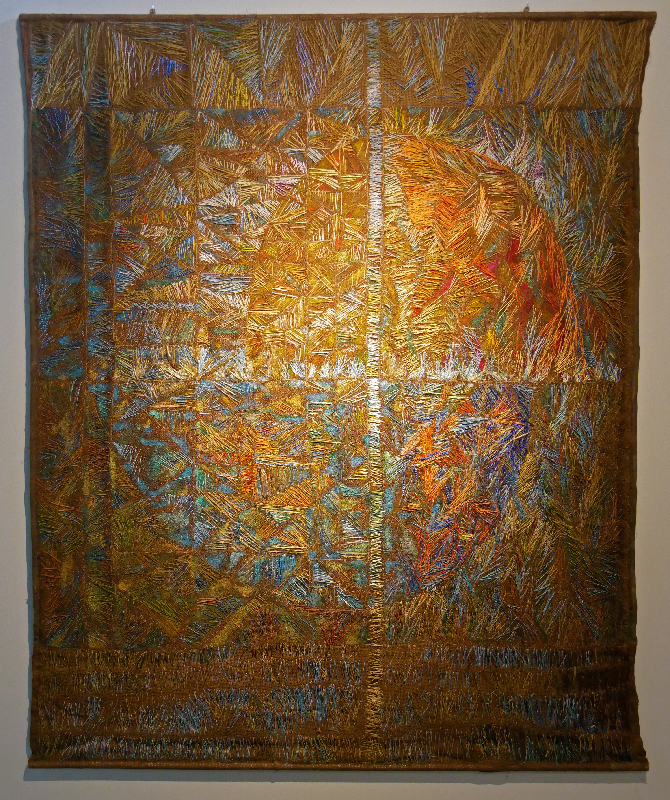

The idiosyncrasies of textile art should be appreciated a little better. I perceive the renewed interest in textiles on the part of fine art as a return to the tangible and haptic qualities of textile art; art needs textiles to provide an impetus. Marta Kovalevska said herself: “Many see textile art as an antidote to the direction in which the world is heading”, and Ann Coxon who curated the Anni Albers exhibition in her museum says she hopes to “bring attention back to time-honoured ways”. One of the two winners of the first prize, created by what is probably the oldest Triennial participant, illustrates that textile art can be compelling not only because it addresses relevant social themes, but also on account of its intensity and beauty.

Beatrijs Sterk