59th Venice Biennale “The Milk of Dreams”, 23 April to 27 November 2022, Part 1, exhibition by Cecilia Alemani at the Giardini and the Arsenalis

The title refers to a children’s book by British-Mexican surrealist artist Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) in which she tells dreamlike tales from a magical world where everyone can change, be transformed, or become something or someone else. The exhibition shows works by 213 artists from 58 countries, divided into three themes: the representation of bodies and their metamorphoses; the relationship between individuals and technologies; and the connection between bodies and the earth.

When asked why only about 10 per cent of the 213 invited artists were male, Cecilia Alemani (only the third female curator at the Venice Biennale) said that it had been the opposite so far, and that this time she had given priority to female artists. For trend researcher Li Edelkoort, it was a similar feeling to having Obama elected President. However, among male art insiders there were doubts as to whether this would be an important biennial…

Having said that, the concept of art was pleasingly broad and included the most diverse so-called folk cultures. For example, there were Vodou flags from Haiti (Myrlande Constant) and folk art paintings (such as those by Palmira from Venezuela). In addition, there was an homage to the Roma identity in the very impressive installation of 12 large-format wall hangings by Malgorzata Mirga-Tas in the Polish pavilion. This aspect will be featured more fully in Part 2, which will go into the country pavilions and accompanying exhibitions around Venice.

I was asked if I thought that this was the best Venice Biennale compared to those of 2017, 2019 or 2022. The ‘Viva Arte Viva’ exhibition, curated by Christine Macel (2017), featured more spectacular textile works by artists such as Ernesto Neto and Sheila Hicks and offered a larger textile festival. As for the textile part of this year’s biennial, although the main theme was surrealism, mostly in the form of paintings, there were also works in a wide variety of materials, including many textiles. I would recommend that anyone interested in textiles should not to miss out on this Biennale. Here are some photos of textile works with brief descriptions of the artists; it is not a comprehensive overview, but I sincerely hope that I have not omitted any important contributions. As mentioned previously, the textile works in the country contributions and the accompanying exhibitions will follow in the second part of this article to be published in June 2022.

Rosemarie Trockel, Germany, 1952

The artist ranks fourth on the art compass, behind Gerhard Richter, Bruce Naumann and Georg Baselitz. From 1998 to 2016 she was a professor at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. She made “being a woman” the subject of her art and formulated criticism of the existing art scene. In the major exhibitions on the subject of art and textiles held since 2014, there have always been isolated works created by her that I have never been particularly impressed with. It was different in Venice, where a whole series of her works were represented, older and many recent ones, knitted pieces and her thread “paintings”; taken as a whole they created a very convincing impression. Maybe this was also due to the brilliant way they were hung in juxtaposition with works by sculptor Andra Ursuta.

Mrinalini Mukherjee, India, 1949-2015

I was astonished that I was able to admire works by this artist which, to my knowledge, have never been shown at the Lausanne Biennale although they were strongly reminiscent of works by Jagoda Buić and other Eastern European artists. Maybe the Lausanne curators’ attention did not extend as far as India, or was the artist a bit too young at the time? Mukherjee works with self-dyed natural fibres, often using the macramé technique. I had never heard of her!

Cecilia Vicuña, Chile, 1948

At the 2017 Documenta, this artist presented an impressive large textile sculpture. In Venice, on the other hand, it took me a little longer to understand the intention behind her work, “NAUfraga” from 2022. She had filled an entire room with her paintings and a spacious sculpture which, however, looked so brittle and fragile that as a visitor, I felt that the artist had not completely mastered the room. I only understood it when I read that her work was about the fragility of Venice on the one hand, and our negligent treatment of the earth on the other.

The artist received the Golden Lion for her life´s work, and the jury stated: “Vicuña is an artist and a poet, and has devoted years of invaluable effort to preserving the work of many Latin American writers, translating and editing anthologies of poetry that might otherwise have been lost. Vicuña is also an activist who has long fought for the rights of indigenous peoples in Chile and the rest of Latin America. In the visual arts, her work has ranged from painting, to performance, all the way to complex assemblages”.

Paula Rego, Portugal 1935

This is another artist I had unfortunately never heard of. Her work “Oratório” consists of an assemblage of 8 paintings and 8 puppet-like sculptures. Here she depicts “fallen” women from the 18th century, who often had to reckon with dire consequences. Another work of hers was called “Gluttony” from the “The Seven Deadly Sins” series; one large and several smaller textile sculptures are on show.

Gabrielle L’Hirondelle, Canada, 1979

This artist collects rubbish such as beer cans and medallions and turns the found objects into sculptures and drawings. Entitled “Counterblast”, her sculpture is a large odalisque with long bunny ears and white flowers in her eyes, lying quietly on her side, showing her eight nipples. This creature of tobacco-filled tights wears amulets, beads, rabbit fur earrings, and jogging shoes on the tips of her bent-back legs. “Counterblast” was the title of a 1604 letter written by the King of England in which he accused the American Indians of having transmitted the bad habit of smoking tobacco to Europeans.

Gisèlle Prassinos, Greece/France, 1920-2015

This French writer of Greek heritage is associated with the surrealist movement. Her writing was discovered by André Breton in 1934, when she was just fourteen, and published in the French surrealist magazine Minotaure and the Belgian periodical Documents 34. Her textile works seem to be very little known.

Bronwyn Katz, South Africa, 1993

Her use of found bed springs and other household materials relates to domestic life – especially the intimate space of the bed, often the site of procreation, birth and death. “Göegöe” is the name of a water snake in the mythology of African peoples

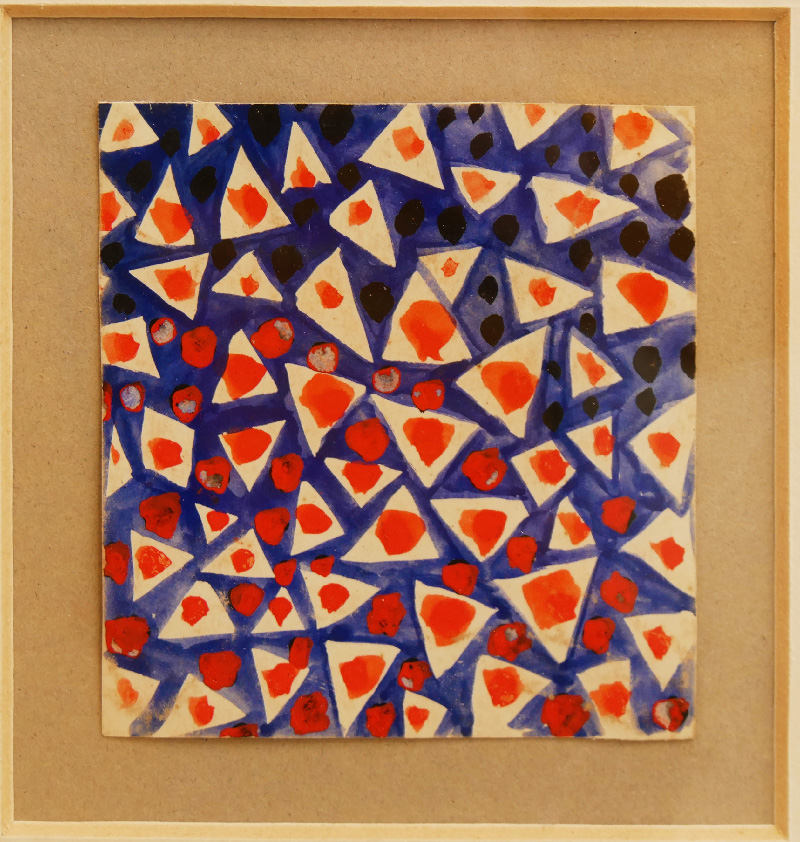

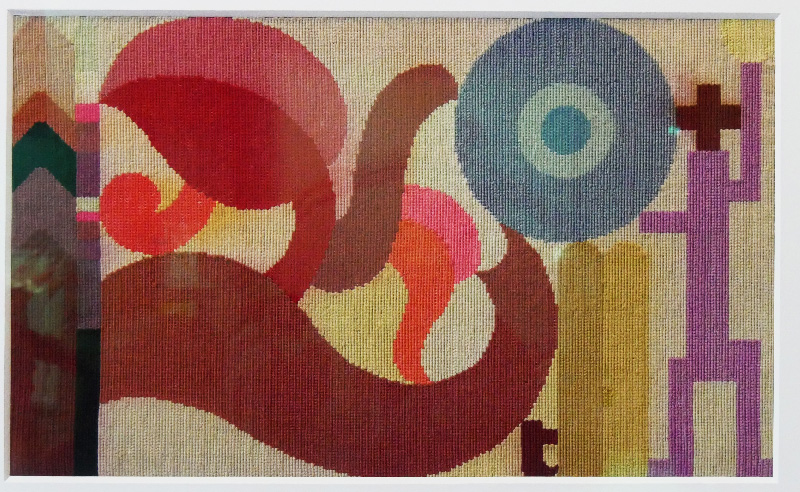

Sonia Delaunay, Ukraine/France, 1885-1979

Sonia Delaunay was a key figure in the Parisian avant-garde of the interwar years. Born to a Jewish Ukrainian family and raised in Saint Petersburg, Delaunay enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe, Germany, at the age of eighteen. In 1905 she relocated to Paris, where Post-Impressionism and Cubism were dominant in the city’s galleries. In this highly experimental climate, Delaunay and her husband Robert pioneered Simultanism, a style of abstract painting that emphasises the transcendental effects of the interaction between colours. The works on paper included here exemplify Delaunay’s application of the principles of painterly abstraction to textile patterns. Seeking compositions that could be realised in loom-woven thread, Delaunay experimented with the rhythm, motion, and depth created by simultaneous contrast, where colours appear different depending on those around them. Some of her designs for fabrics from 1925 to 1930 were shown in Venice, which looked very up-to-date and lacked nothing in terms of freshness and luminosity.

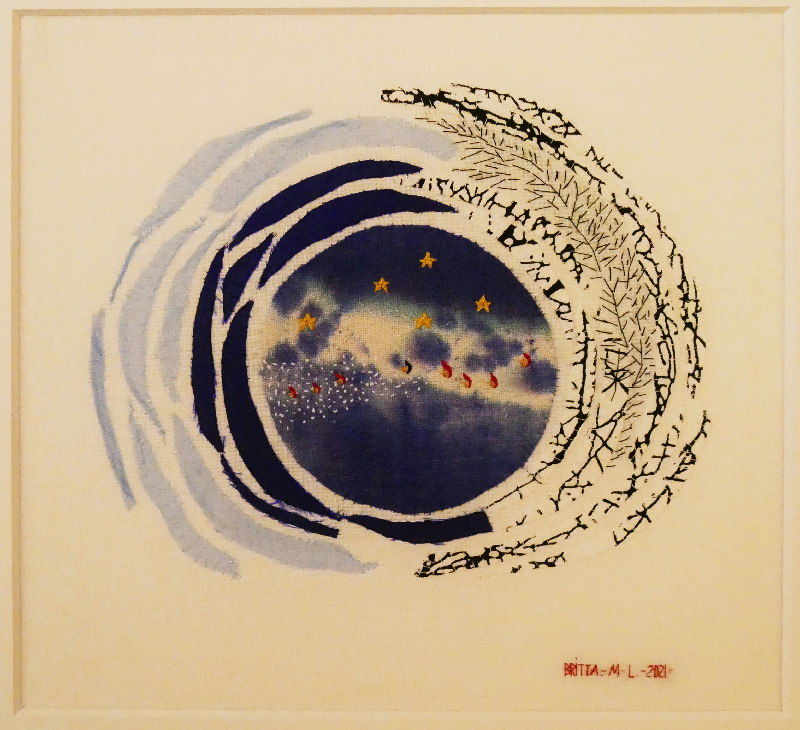

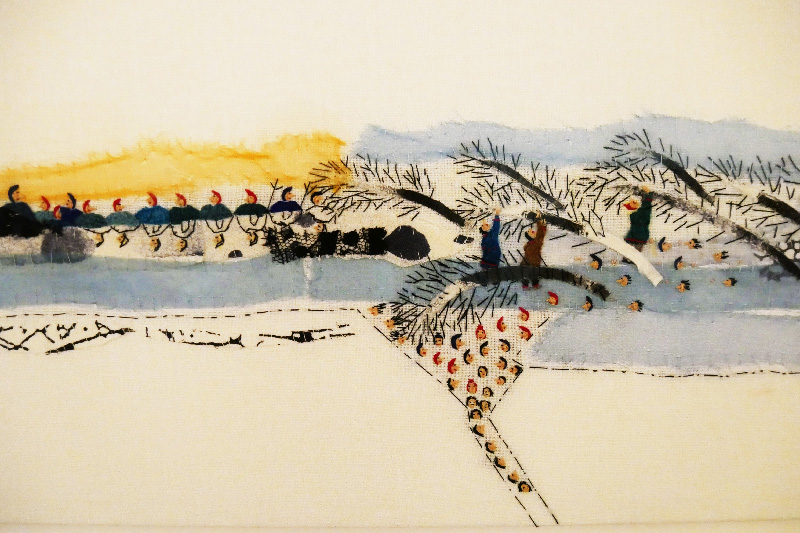

Britta Marakatt-Labba, 1951, Sàpmi, northern Sweden

he artist was born into a family of reindeer hunters in Sàpmi, home to the Sámi indigenous community. Her artistic practice has linked methods of visual storytelling to the Sámi people. Marakatt-Labba is known for her embroidery work “Historjá”, which she exhibited at Documenta in 2017. Her new works are “Milky Way” and “In the Footsteps of a Star”, both from 2021. They are not quite as spectacular as the work presented in Kassel, but it is impressive that the artist continues with her means to save the art and culture of the Sámi who still live in harmony with nature.

Myrlande Constant, Haiti, 1986

Constant’s large-scale textile tableaux—”paintings with beads,” according to the artist—draw on Vodou myths and Haitian visual traditions. Her works contain intricate beadwork and alternative interpretations of the Haitian religion’s myths: amid her vibrant landscapes, figures of different races, sects, and nationalities engage in mundane rituals together. Religion, in particular human relationships with loas, representatives of God in the physical world in the Voudou, deeply informs her work

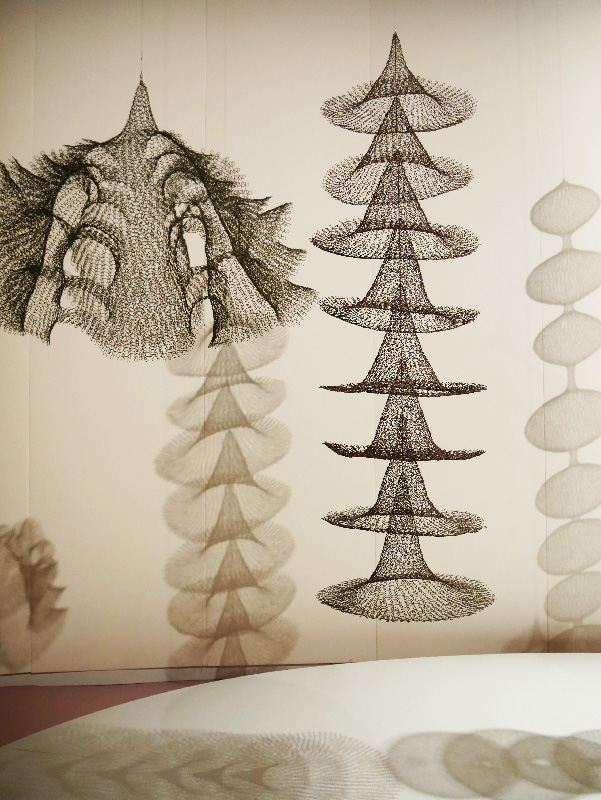

Ruth Asawa, USA, 1926 – 1013

Ruth Asawa began making art as a teenager while forcibly detained by the US government in an internment camp during World War II alongside her family and thousands of other people of Japanese descent. In 1949, Asawa began constructing suspended sculptures, transforming everyday industrial materials – rough brass, steel, and heavy copper wire – into sinuous and graceful spherical forms, which, although three-dimensional in volume, do not contain any interior mass.

Asawa’s work is featured in a series of time capsules, which “establish dialogues and rhymes across generations.”

Igshaan Adams, South Africa, 1982

Raised in Bonteheuwel, a former segregated township in Cape Town, South Africa, Igshaan Adams grew up in an acutely challenging setting, against which he has maintained a multifaceted racial, religious, and sexual identity. In some tapestries, Adams records other types of movement by drawing from “desire lines,” unplanned paths made as a consequence of erosion from foot traffic, which throughout the Apartheid era were used to connect communities that the government wanted to forcibly separate. For The Milk of Dreams, Adams zooms in on desire lines between the Bonteheuwel train station in Cape Town and Epping, one of the city’s industrial neighbourhoods, where many seek work.

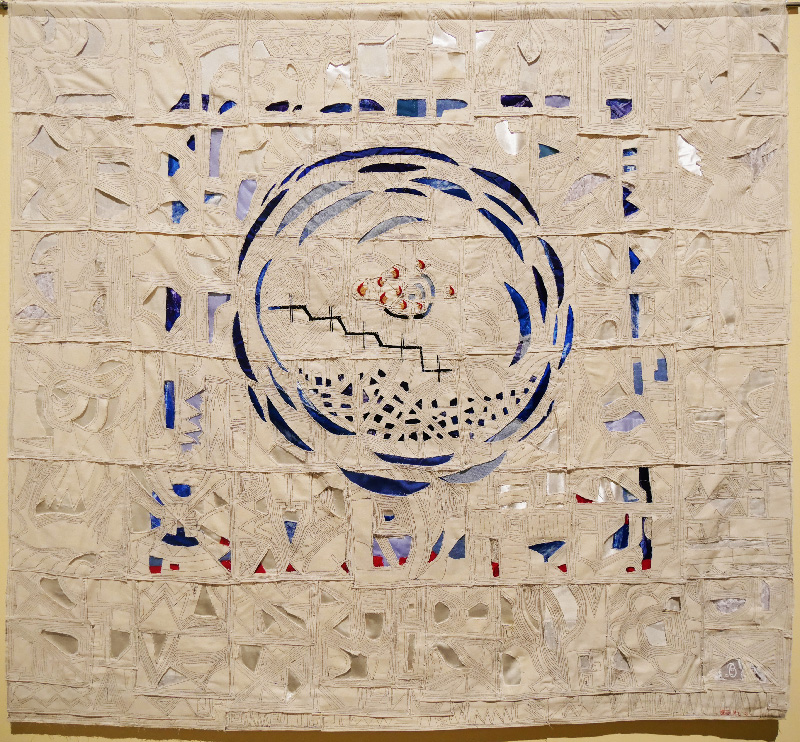

Tau Lewis, Canada, 1993

Tau Lewis transforms foraged textiles and artefacts through painstaking processes of sewing and quilting into imaginary talismans and magical beings who inhabit sci-fi worlds. Lewis creates subversive monuments, paying tribute to philosophies of material ingenuity as an act of agency across Diaspora communities. Lewis also dissolves the space between artistic and political poles, especially between practices traditionally delineated as craft, ritual, or art. The artist positions textiles and hand-making at the centre of an exploration of identity, bodies, and nature.

(1896, Lübben, Germany – 1924, Hamburg, Germany, 1899 – 1924, Hamburg, Germany.)

Mask figures, 1924 / 2005–2006

Replicas and photos of the original works. Schulz and Holdt created a series of fantastical costumes that transformed dancers into a type of hybrid artwork; photo Beatrijs Sterk

Lavinia Schulz & Walter Holdt (1896, Lübben, Germany – 1924, Hamburg, Germany, 1899 – 1924, Hamburg, Germany.)

Along with her husband and artist partner Walter Holdt, Lavinia Schulz performed Expressionist dances from 1919 until 1924 in Hamburg in a style that built on varying intensities of “creeping, stamping, squatting, crouching, kneeling, arching, striding, lunging, and leaping in mostly diagonal spiralling patterns.” Schulz and Holdt created a series of fantastical costumes that transformed dancers into a type of hybrid artwork.

(From a text by Madeline Weisburg in the Short Guide). Exhibited at the Biennale under ‘Time capsule V: Seduction of the Cyborg’.

(1896, Lübben, Germany – 1924, Hamburg, Germany, 1899 – 1924, Hamburg, Germany.)

Mask figures, 1924 / 2005–2006

Replicas and photos of the original works. Schulz and Holdt created a series of fantastical costumes that transformed dancers into a type of hybrid artwork; photo Beatrijs Sterk

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Switzerland (1889–1943)

Sophie Taeuber-Arp was a key member of the Dada movement who eschewed boundaries between fine and applied arts and, despite living through two world wars, produced works in which joy and colour triumph above all. Taeuber-Arp studied textile design at the School of Arts and Crafts in St. Gallen and dance at the Laban School in Zurich. From 1916 to 1929, Taeuber-Arp taught textile design at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts, a position that supported her and her husband, the artist Jean Arp. Upon moving to Zurich in 1915, she began making textile works and geometric non-representational paintings she referred to as “concrete.” A signatory of the Zurich Dada Manifesto, Taeuber-Arp performed often at the movement’s celebrated Cabaret Voltaire, for which she also designed sets, costumes, and small marionette puppets that don a robotic or cyborgian futuristic sensibility. In 1926, Taeuber-Arp moved to France, splitting time between Strasbourg and Paris. In 1940, she left Paris in advance of the Nazi occupation. In 1942, she returned to Switzerland, where she died from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning at the age of fifty-three.

Tetsumi Kudo, Japan, 1935 – 1990

Kudo was part of a generation of Japanese artists that was highly sceptical of traditional society in the wake of the events of World War II.

After moving to Paris in 1962, Kudo began creating works guided by his feeling that, in a “New Ecology” where humans, nature, and technology had become intertwined, ethical values were as exchangable as commodity goods.

Kudo often employed fluorescence to create an uncannily high-tech aura, as in the luminous “Flowers” dating from 1967/68. His post-natural visions capture the ambiguous detachment of a world reshaped by human desire

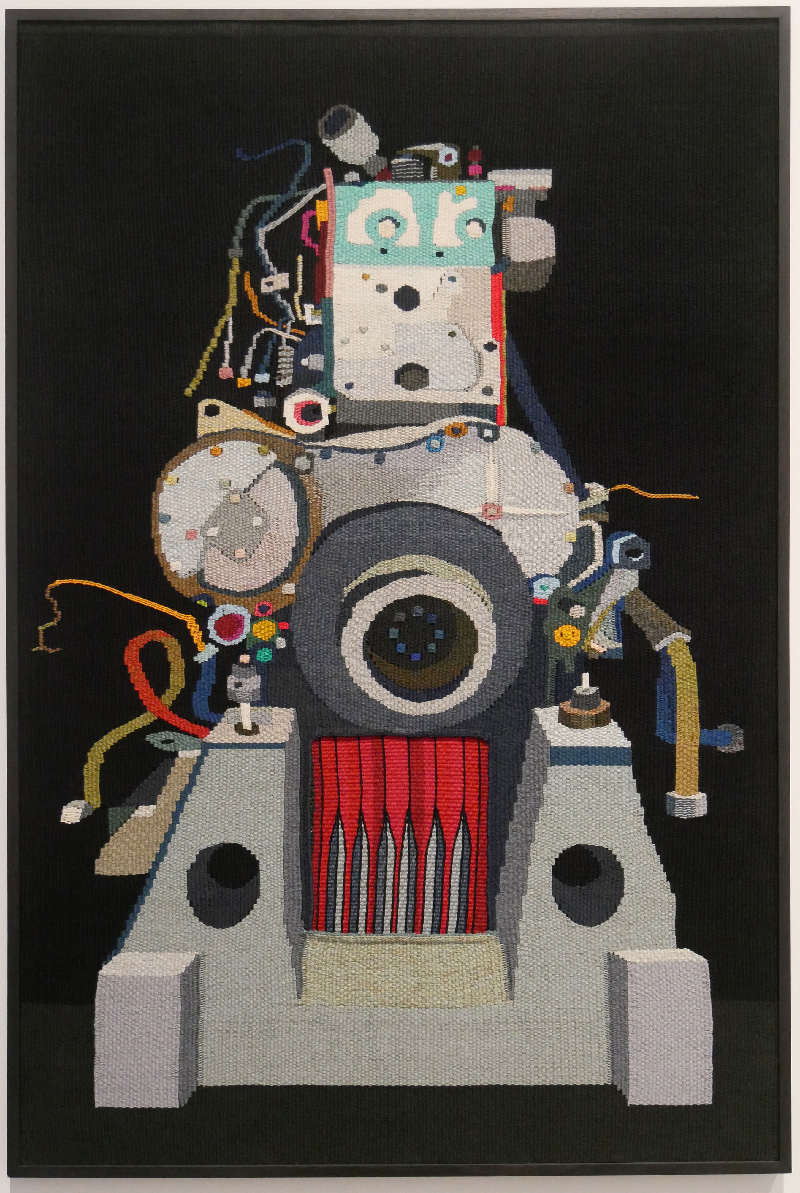

Zhenya Machneva, Russia, 1988

Zhenya Machneva’s tapestries transform the gleaming steel fantasy on which the Soviet Union’s economic fortune was to be built into a world of the uncanny. Inspired by a visit to the Leningrad telephone equipment factory where the artist’s grandfather worked for forty years, Machneva intertwines images of obsolete factories, industrial landscapes, and mechanical objects with the digital present. Created on manual looms, Machneva’s tapestries stand in contrast to the speed and efficiency of contemporary technologies while mirroring the work ethic that made industrial labour possible in the first place.

Note: The texts were either written by Beatrijs Sterk or taken from the inscriptions and text panels of the Biennale