Rediscovered weavers

Else Mögelin and Johanna Schütz-Wolff

Last April I was invited by friends from he Polish Art Academy in Stettin to an exhibition of Bauhaus weaver Else Mögelin, not shown for the past 30 years . She now has found a renewed public interest in her work by two exhibitions this year: The first was „I wanted to weave against all obstacles” from 2.12.2023 til 3.3.2024 at the Brandenburg Modern Art Museum in Germany and an even more detailed exhibition “Else Mögelin – Bauhaus and Spirituality in Pomerania” from 11.4 til 9. 6. 2024 in Szczecin, Poland. From 1927 – 1942 she headed the textile workshop at the Municipal Crafts and Applied Arts School in Szczecin, which cooperated closely with the Municipal Museum under the direction of Walter Riezler. Having written about textile art since the start of our magazine Textile Forum( German language first and English since 1993), I was not aware of the importance of her work, even though I had met her in person, end of the 70s!

I had already experienced the same surprise about the fact that a talented weaver artist could be nearly overlooked by history, when visiting the exhibition on weaver Johann Schütz-Wolff at the Grassi Museum of Applied Art from 21. 5. til 20.11.2015. She had been teaching weaving at Burg Giebichenstein in Halle, Germany, this art school together with the Bauhaus were considered two of the best educational institutions at the time. The Dessau Bauhaus emphasised a unification of the arts and crafts in architecture and industry, while Burg Giebichenstein gave greater prominence to an integration of the crafts and arts in the spirit of the German Werkbund (form follows function). Bauhaus was dissolved because it was felt to be too progressive by the National Socialist rulers. Burg Giebichenstein continued to exist but was greatly restricted, and gradually fell into oblivion.

How could this happen, when Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl were always mentioned when textiles at the Bauhaus were discussed widely? There is a wide range of textile careers/fates under National Socialism, from being killed as was the case with (jewish) Bauhaus weaver Otti Berger (Auschwitz 1944), to immigration to the USA (Anni Albers) or to Switzerland (Gunta Stölzl). The fact that these weavers had to leave their country, was beneficial for their work because they could furthermore work in a progressive way. Especially Anni and her husband Joseph Albers brought their Bauhaus ideas to a new life at the Black Mountain College, thus teaching younger textile artists like for example Sheila Hicks and others.

Those who stayed in Germany during the Nazi-era had their works being taken out of important museums as “degenerate”. Johanna Schütz-Wolff had destroyed 13 of her own tapestries because her husband was already in the focus of the regime due to his publications. She lost her job at the Burg Giebichenstein textile workshop and did not receive weaving materials during war time. Else Mögelins tapestries also were taken from museum collections as “degenerate”. She survived as a weaver because she had a network of local supporters in Sczcecin, helping her to get at least some commissions from the regime together with weavings for churches.

Earlier I had met another weavers of that time, Alen Müller-Helwig (1901 – 1993), who had also made some abstract weavings in the 20s. She took a full turn towards weaving nature motives after designs by the painter Alfred Mahlau, who was accepted by the regime. Her workshop had no problems at all, she was receiving some 70 commissions for public buildings and she also was the one to distribute the weaving materials. Asked how she felt about her colleague not receiving any material, she answered that it was awful (but inevitable as it seemed). My conclusion is that the Nazi regime stopped the whole modern development of textile art, not only in the time of their ruling but also later on; it seemed to me that textile art did not reach the fame of the American, the Polish and the Japanese textile artists shown at the Lausanne Biennials. Some few German textile artists coming to my mind from the Lausanne era, are Sofie Dawo and the Romanian-born Ritzi Jacobi. Rosemarie Trockel,who does not identify as a textile artist and never showed her work at Lausanne, is often mentioned as German textile artist, because she made conceptual art on knitting machines.

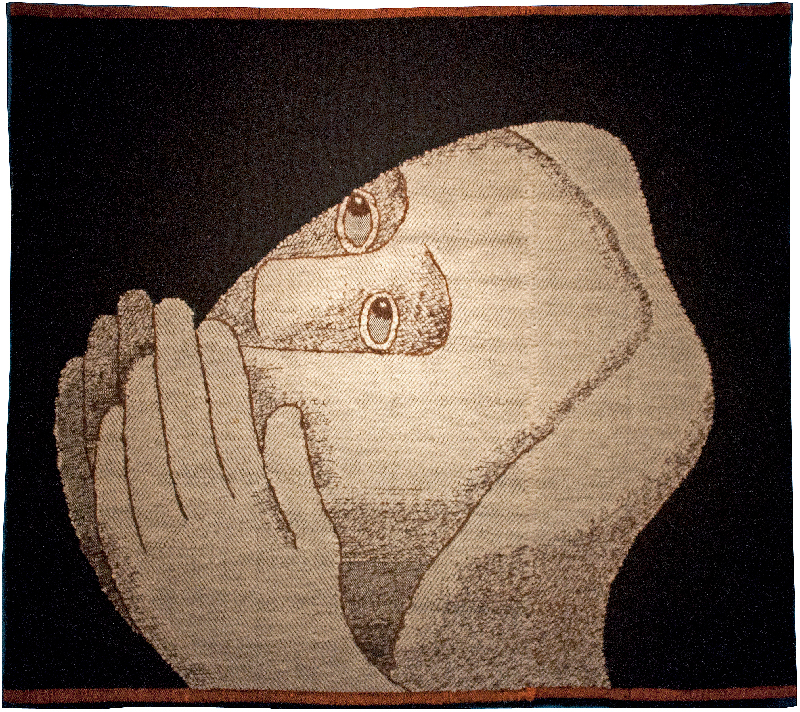

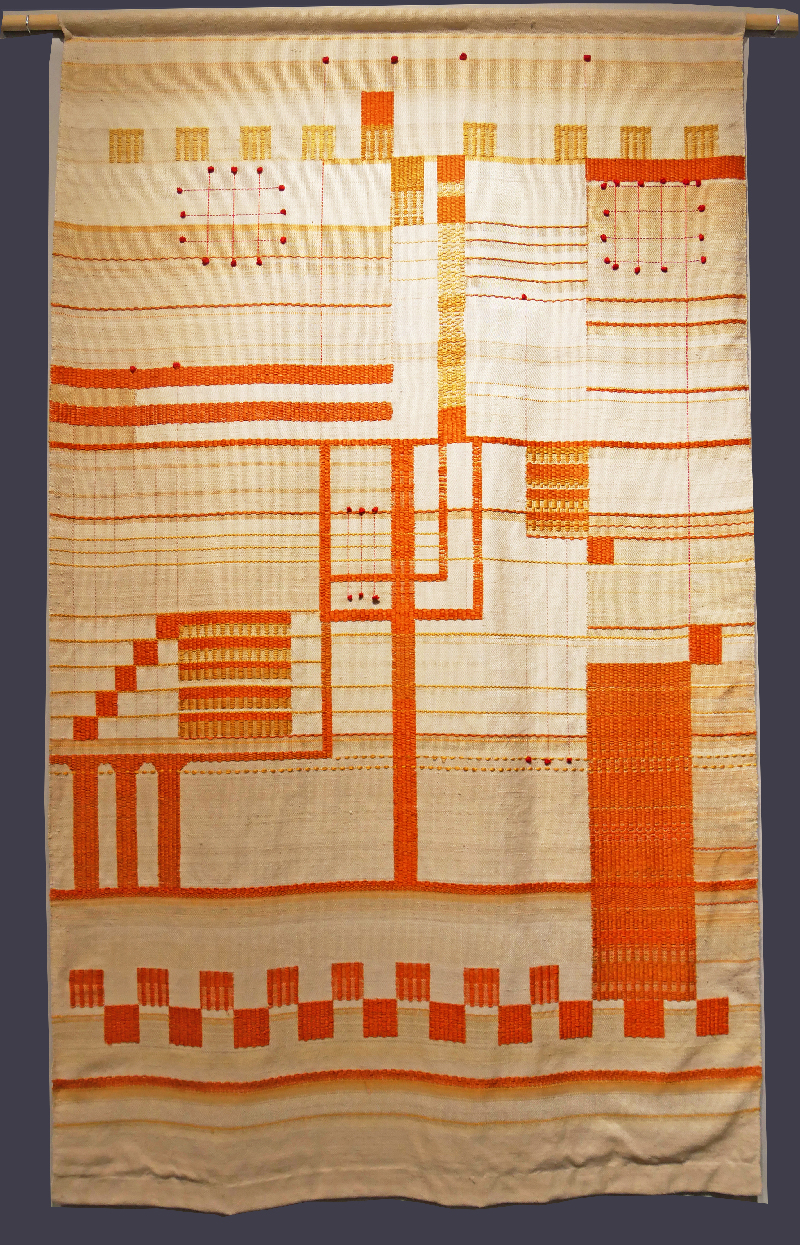

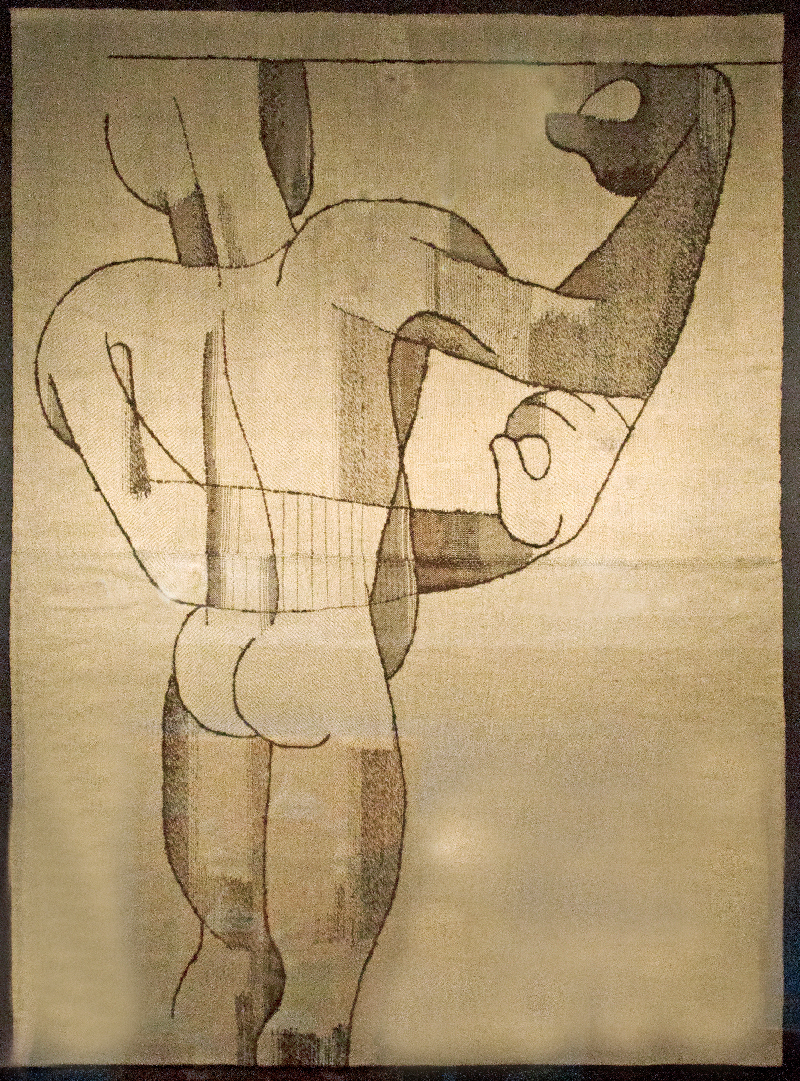

The two weaver artists , Else Mögelin and Johanna Schütz-Wolff, who are now back in the public focus, were both tapestry weavers using warp and weft, weave structures and various materials. Unlike the tapestries with completely covered warp, this way of weaving was called semi-gobelin. French gobelin weaving was considered “the bastard of painting”(as Johanna Schütz-Wolff named it) whereas these weaver artists made use of new stylistic devises opening the warp and making crossed threads visible to show the art of weaving. Both artists also did not always use a precise cartoon but worked from a small sketch or from markings on the warp, at least when they wove themselves (Else Mögelin also had other weavers working for her). Truth to material and authenticity were espoused both by the Dessau Bauhaus and the Burg Giebichenstein school of Art and Design in Halle. This principle of artists weaving their own work, being true to the materials employed and authentic, and the power of experimentation and abstract design is considered the beginning of weaving as an art form in its own right. This happened in the beginning of the 1960s starting with the Polish weavers artists at the Lausanne Biennials. We can see these ideas emerging already in the 1920s, making Else Mögelin and Johanna Schütz-Wolff important as forerunners of the start of textile art as an independant art form (in contrast to applied art).

The lives of these two expressive weaver artists:

Else Mögelin(1887 – 1982 ) came from her mothers side from a Dutch family of textile manufacturers, her father was a high school teacher. She studied design at the Berlin Royal Art school in 1907, works as a design teacher. She studied with textile designer Alfred Mohrbutter at the school of Art and Design and took a course for decorators at the Reimann School, co-organised by the German Federation of Craftsmen (Deutsche Werkbund). She tooks part in exhibitions since 2017.

In 1919 she took part in the important exhibition Kunstausstellung Berlin (Berlin Art Exhibition) and started the pre-course by Johannes Itten and Paul Klee. For a year she worked at the Naum Slutzki metall workshop. In 1920 she worked at the pottery workshop of Gerhard Marcks and Max Krehan in Dornburg, the only Bauhaus external side. Paul Klee seemed to have directed her towards textiles, from April 21 she worked in the textile department, headed by Helene Börner and George Muche, where she finished her art education 1n1923.

In 1923 she joins the progressive Craft Colony Gildenhall near Neu-Ruppin and takes over the textile workshop there. From 1926 she is leading this workshop together with weaving master Otto Patkul Schirren. She works for the famous Grassi-fair in the Leipzig Museum of Applied Art, and for Walter Riezler, Director of the Sczcecin Municipal Museum and curator of the German Pavillion at the Monza Biennial 1925.

In 927 Else Mögelin became head of the Sczcecin Art and Craft School, she stayed as an advisor for the Gildenhall Weaving Workshop.

In 1930 there are several exhibitions about tapestries as well as about “School and Craft”, also the first exhibition at the Sczcecin museum of the progressive group “New Pommerania” (a.o. with Mies van der Rohe, Oskar Schlemmer). Later Else Mögelin will see the early 30s as her best time, she also meets her partner, weaver Jane Ganzert, during this period. Together with her she has a private workshop (apart from the school weaving workshop), working for churches in Pommerania. In 1932 the Municipal Museum organises the exhibition “Tapestries and Textiles”, devoted to Else Mögelin and her students.

In 1933 with the advent of the Nazi-regime, the avantgarde is heavily critisised, the Bauhaus is dissolved, and the whole educational system reorganised. Mögelins works are taken from museum collections as “degenerated”, but thanks to her friends and colleagues she manage to function in the local art scene. She takes part in the exhibition “Pommerian Artists of Today” in 1934 at Sczcecin Municipal Museum, as also in the supraregional “Weavings and Ceramic Today” in 1935.

She even did get some commissions for public buildings in Sczcecin thanks to her good contacts.

In 1943 the Sczcecin School Weaving Workshop is burnt down leaving Mögelin without work and in 1945 the Russian front is forcing Else Mögelin to flee to Hamburg, where she receives a job as Lecturer for textiles at the State Art school.

At the 9th Milan Triennial in 1951 she represents the German Federal Republic with the tapestry “The Earth” and receives a bronze medal. After her retirement in 1952 she creates many textiles for different churches. In 1954 she creates a 7 meter high tapestry “Christ”

Von 1955 – 1962 she designs the “Bugenhagen Tapestry for the Pommerania Chapel at the Nikolai Church in Kiel.

The tapestry “People” is created together with Bauhaus weaver Marie Thierfeldt for the German Embassy in Stockholm.

Else Mögelin dies in 1982 in Kiel.

Johanna Schütz-Wolff 1896 – 1965 was born as the daughter of architect Gustav Wolff and his wife Anna. She and her sister Thekla were educated by their parents in design, lacemaking and weaving. From 1915 -1918 Johanna is visiting The Halle Art and Craft School run by Paul Thiersch. 1918/19 she studies at the Munich Art and Craft School. From October 1920, Thiersch assigned her the management of the newly installed Textile Workshop at the Halle School, from 1921 on the weaving workshop is installed in the Burg Giebichenstein (Giebichenstein Castle).

Johanna Wolff met the theologian Paul Schütz and marries him in 1923, they have a daughter Anne.

In 2025 Johanna Schütz-Wolff stops teaching and moves with her husband to Schwabendorf near Marburg, where he has a parish position. She is weaving tapestries and in spite of the seclusion, she is taking part in many exhibitions and attracts attention by her expressionist tapestries.

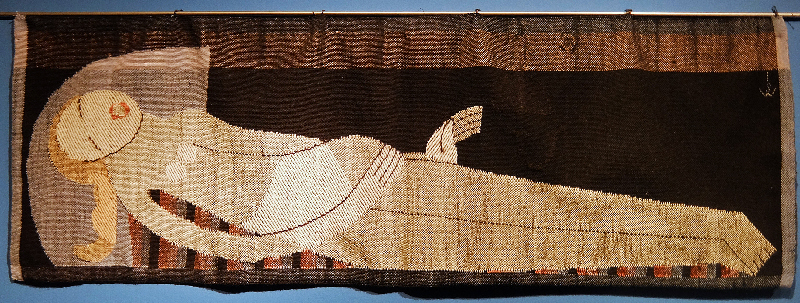

She participated in important exhibitions like the “German Art”exhibition in 1928 in Düsseldorf, where she won a silber medal for her work “Die Liegende (The Lying)”. In 1929 she participated in the exhibition “Moderne Bildwirkereien (Modern Tapestries) by gallery director and art historian Ludwig Grote at Kunstverein Dessau with the aim of “leading tapestries out of their exile in the applied arts”. This exhibition toured nine German cities, displaying tapestries by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Hans Arp, Wenzel Hablik, Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl. Johanna Schütz-Wolff made a great impression with her work “Male Nude” at this exhibition.

The Nazi-period was fateful for this talented weaver, one of her works was confiscated by the regime, her husbands book “ The Anti Christ” was indexed by the Gestapo and all further copies destroyed. She herself did not receive invitations for exhibitions anymore and her applications for educational activities (a.o. at the Halle Art and Craft School) remained unsuccessful. When a control visit by the Gestapo was expected, she destroyed herself 13 of her weavings with a scissor..

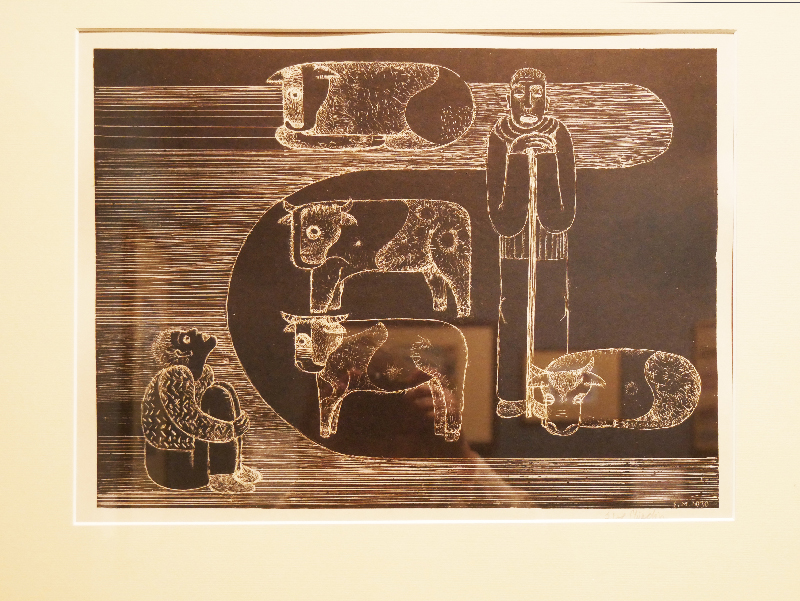

In her work she turned to more religious subjects and worked for churches. In 1940 her husband did receive a full-time pastor position in Hamburg but was called for military service in 1941 until the end of the war. After 1945 Johanna Schütz-Wolff returned to tapestries again but from on 1950 she concentrated more on woodcuts, from 1960 on monotypes. Johanna Schütz-Wolff dies in 1965.

A number of her Tapestries are now in public collections such as The Bavaroa State Painting Collections, the New Munich Collection, the Berlin National Gallery, the Schloß Rheydt Municipal Museum in Mönchen Gladbach, the Hamburg Museum of Arts and Crafts, the Hessian State Museum in Darmstadt, the Art Gallery Moritzburg, Halle and the Grassimuseum Leipzig.